A majority-Hispanic neighborhood was deemed “endangered” by the city. What will it take to create attractive places where residents can be safe and engaged?

From its earliest roots, Denver’s Westwood has been a neighborhood that largely served poor people. However, as the subject of a ULI Advisory Services panel on creating healthy places, this largely Hispanic neighborhood in the southwest part of the city might finally get a boost toward becoming a vibrant destination and healthy place to live.

Westwood was the third Colorado community analyzed by a ULI panel under the auspices of the Healthy Places: Designing an Active Colorado initiative, sponsored by the Colorado Health Foundation (CHF). Over five days in May, ULI panel members walked the streets of Westwood, toured the area by van, and interviewed more than 100 stakeholders. At the conclusion of panel’s work, more than 100 people came to a local church to hear the panel’s recommendations, presented in English and Spanish.

Related Content: Health in the Suburbs: Arvada, Colorado

Related Content: Health in Rural Areas: Lamar, Colorado

The neighborhood started out under adverse conditions. “Westwood developed during the depression when times became hard; cheap land was the only land people could afford,” according to a 1944 newspaper article. "[Westwood] became a shack town, trailer town and tent town.”

In a 1986 neighborhood plan by Denver Planning and Community Development, Westwood was described as an “endangered” neighborhood that has been “neglected by the city of Denver (in terms of long-range planning, services, zoning, etc.) and suffers from several major areas of concern.” Among the problems cited in the plan were a poor neighborhood identity, poor housing stock and high turnover, inappropriate zoning, a prevalence of undesirable businesses, deterioration of business areas, and a lack of open space.

Little has changed in the 27 years since that report was completed, or for that matter, since Westwood was annexed by the city in 1947, according to Paul Lopez, the energetic and charismatic Denver City Council member who represents the district that includes Westwood.

“We have a lot of challenges, this is true,” Lopez told the ULI panel members as they gathered in the cramped offices of BuCu (Business and Culture) West Development Center along Morrison Road, the main business artery through Westwood and six blocks from where Lopez grew up. Many commuters from the suburbs west of Denver’s city limits use Morrison Road as a shortcut to downtown Denver without ever stopping in the neighborhood.

Slowing traffic along Morrison Road is one of the many challenges facing Westwood, a neighborhood with a population of 15,486, according to the 2010 U.S. census. The community, covering 958 acres (358 ha) is 81 percent Hispanic, and the median household income is $37,961, compared with $55,129 for all of Denver, according to the private Piton Foundation in Denver.

The ULI panel, led by chair Ed McMahon, ULI senior resident fellow, was composed of Kamuron Gurol, director of community development for Sammamish, Washington; Debbie Lou, a program analyst for Active Living Research in San Diego; James Moore, vice president and senior professional associate for HDR in Tampa, Florida; Ralph L. Núñez, principal partner of DesignTeam Plus in Southfield, Michigan; James Rojas, urban planner and cofounder of Latino Urban Forum in Los Angeles; David Scheuer, president of Retrovest Companies in Burlington, Vermont; and Elizabeth Shreeve, principal of the SWA Group in Sausalito, California.

Rojas, who has studied Latino culture for more than 20 years, said neighborhoods such as Westwood can be found throughout the United States.

“From our interviews, one thing that kept coming up is how do we start a plaza in Westwood?” he said. “You find plazas and mercados everywhere in the Latino culture. A plaza is a place where you can really capture the Latino buying power.” Ideally, it would serve as a place that would be easy for Westwood residents to reach by foot or bike, plus serve as a destination for people throughout the area, as well as tourists, Rojas said.

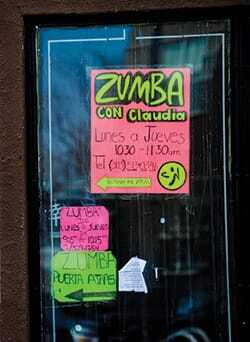

He said plazas created by developers have “transformed some of the most dangerous parts of L.A.,” and Westwood is an ideal candidate for a plaza that could feature dancing, mariachi bands, food, and shops.

Panelists said Westwood faces numerous challenges that make it difficult to foster a healthy lifestyle, including:

- A lack of adequate parkland and green space. The neighborhood has only one park, though a second one is in the early stages of construction.

- Few places where teens and residents can gather for public events or celebrations.

- A lack of public transportation.

- Many unpaved alleys, which attract illegal dumping. Complicating the situation, some alleys are owned by residents, while others are owned by the city.

- Narrow, broken, or nonexistent sidewalks.

- An automobile-oriented street design that is not pedestrian friendly. Westwood’s walkability score is only 48 on a 100-point scale.

However, the neighborhood also has significant assets, the panelists noted, including hard-working people who place a high value on family and have a strong belief in education; a distinctive multicultural identity and history; and a diverse group of nonprofit organizations working to improve the neighborhood.

The ULI panel proposed several of what it termed “big ideas” for the community, including:

- Create a unique identity with a new Latino Cultural District. “Westwood has a very strong, Latino cultural heritage,” panelist Moore said. “And its location a few miles from downtown is great. It is very well located. It is close to the heart of the metropolitan area, and that is important to keep in mind. It is close enough to other parts of the city that you can really build something special here.” One component could be a new plaza created in the heart of the neighborhood.

- Create a system to pave alleys and repair and widen sidewalks. Also, many blank walls in the neighborhood, which has a high concentration of Asian restaurants and shops, should be painted with murals to reflect either Latino or Asian cultures. The murals that have been painted stand out, Moore said, as do buildings that have been painted bright colors. “It is amazing what a little imagination and paint can do for the fabric of the neighborhood,” he said. “That should be encouraged.”

- Transform Morrison Road, which diagonally bisects Westwood, into a Main Street with community space, shops, restaurants, grocery stores, and housing. The new Main Street should connect Denver’s neighborhoods rather than divide them. Widened sidewalks along Morrison Road would narrow the vehicle lanes, slowing traffic, panelist Shreeve said. Rows of trees should be planted along the street, and better lighting should be installed. New buildings should be oriented to the street, and intersections should be used as places for art, murals, and music and other performances. “That’s more eyes on the street,” making the neighborhood safer, she said.

- Substantially improve the neighborhood’s stock of parks and green space. The neighborhood should have ten acres (4 ha) of park space for every 1,000 residents, but instead has 1.2 acres (0.5 ha). “It only has 10 percent of what is standard,” Shreeve said. One possibility, already being championed by Lopez, is to convert the Weir Gulch, a floodplain area in northwest Westwood, into a park area.

- Connect the neighborhood to the rest of the city. The nearest light-rail station is 3.2 miles (5 km) away, and that is too far, Shreeve said. She suggested a circulator shuttle system that would serve a nine-mile (14.5 km) route, serving most major intersections in the neighborhood.

The CHF has hired Denver-based Progressive Urban Management Associates (PUMA), a Denver-based consulting firm, to help each of the three communities visited as part of the Healthy Places initiative to implement the ULI recommendations. Communities are eligible to seek up to $1 million each from the CHP to carry out the recommendations.

“The timing of this ULI panel may be ideal to actually get a number of noble ideas advanced in Westwood,” Segal said.

Lopez said he was thrilled with the recommendations from the ULI panelists. “I want to thank you, the folks at ULI, for spending the last week in Westwood, walking the neighborhood, talking to folks in the neighborhood, and figuring out the lay of the land,” he said.

However, he said it is important to put the ULI input into perspective. “I want folks to be aware this is part of a larger community process,” he said. “It is one piece of the community puzzle. What happens next depends on us as a neighborhood. We want—I want—to make this a community that moves from blight to beauty. This is just the beginning.”

The Building Healthy Places Initiative leverages the power of ULI’s global networks to shape projects and places in ways that improve the health of people and communities. Learn more.