Remote work’s impact on demand for office space is still working its way through the system. Technology companies such as Google have led the way in requiring workers to return to the office, with expectations that employees are there three to five days a week.

Employees get the message that career advancement may depend on their showing up regularly in the office, as companies believe that face-to-face contact there helps promote productivity and their work culture. Nonetheless, the cumulative effect of fallout from Covid-19 is causing many office buildings—most notably ones of B and C quality—to suffer potentially fatal levels of vacancy. Ironically, Class C is doing better than Class B because it is cheap. Class B and lesser Class A are suffering the most because they are neither good nor cheap.

Buildings that are considered the “worst” office buildings—typically Class B—often are the best candidates for conversion to residential uses. The smaller floor plates and high floor-to-floor ceilings lend themselves to residential conversion. Office building HVAC ducts and electrical wiring reduce 11-foot (3.3 m) floor-to-floor stories to about 8 feet (2.4 m) in height. Such ducts and cabling can be stripped back for residential uses, leaving 10-foot (3 m) ceilings that feel spacious and luxurious to residents.

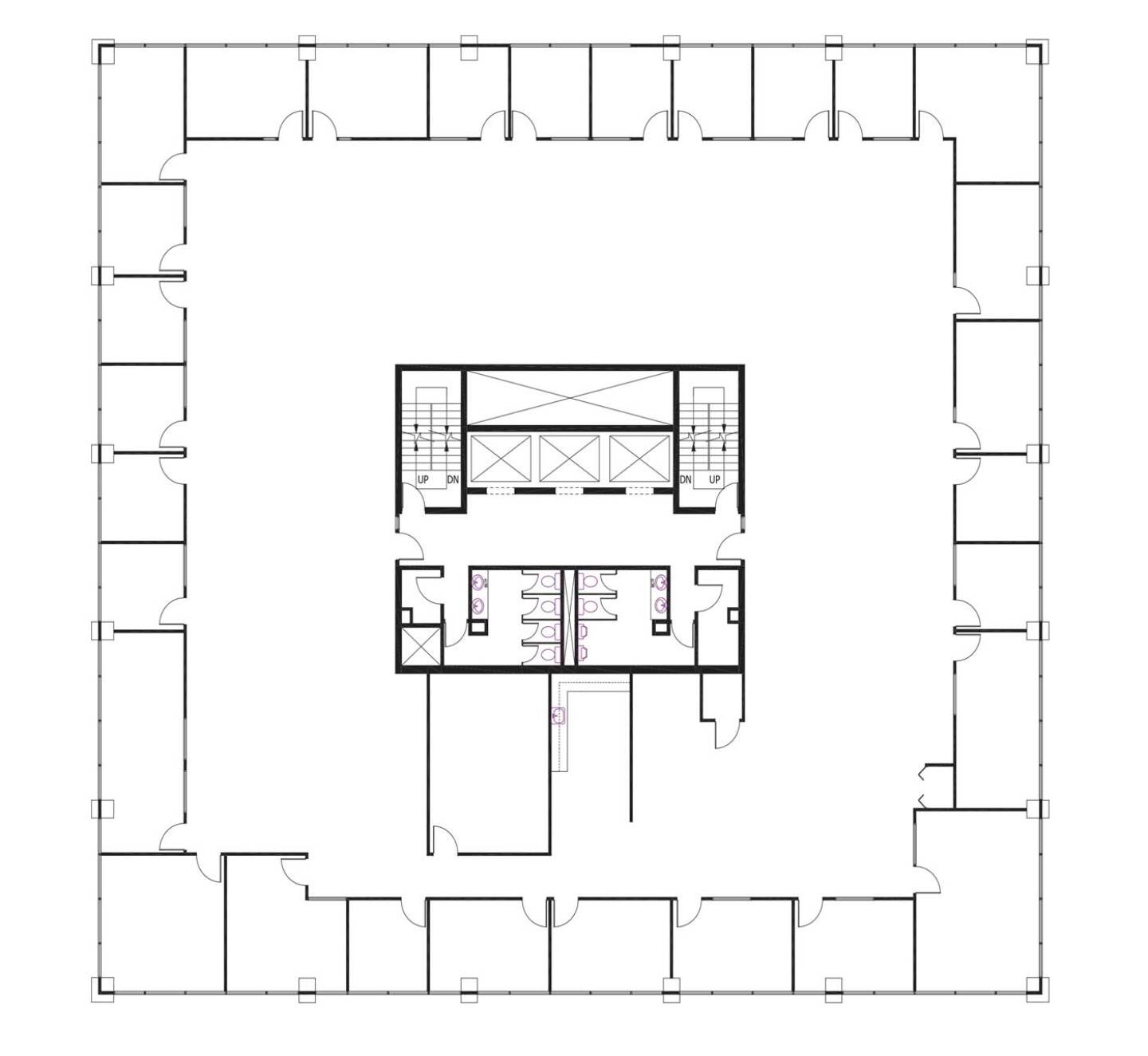

Gensler developed scoring criteria for evaluating the suitability of buildings to conversion from office to residential. The criteria shown in Figure 1 consider the site context, building form, floor plate size, envelope, and servicing. These scoring criteria lend the greatest weight to building form (its shape and ease of unit design) and floor plate (distance from windows to core and elevators).

Public support is necessary for a successful conversion program. Calgary, Canada, which has suffered from a large number of office building vacancies, has one of the most successful office-to-residential conversion programs in North America. By shortening approval timelines and offering subsidies, Calgary has demonstrated that conversions can be economically attractive. Cities can catalyze the process of conversion by offering tax incentives such as those for new construction as suggested by Brookings, or by developing an inventory of potential conversions as suggested by Graham and Dutton.

Beyond supporting conversions themselves, cities must also put a clear plan in place to address the changes that will occur as conversions happen. Conversions can help solve the problem of vacant office space and add to the housing stock, but they bring a new set of problems as people move into a neighborhood that might not have the resources to support increased residential density, such as schools and grocery stores.

Public officials and developers must work in harmony with one another to achieve their shared goals. This coordination might take the form of a public park provided by the developer or area-specific policies that focus on conversions in a defined area to meet a city’s strategic objectives and oversight capacity as suggested by Brookings and also by Smith and Greenhalgh in a 2016 article in Planning Theory and Practice.

A city that converts empty office to multifamily in its downtown gets clear social, environmental, and economic benefits. This solution should not be considered a panacea for the housing shortage, however, as downtowns constitute only a fraction of cities as a whole. Although conversions might not solve the housing crisis in many cities, as the office issue worsens, the number of units being created has jumped. Gensler estimates that 10 percent of downtown gross floor area will be converted to residential. It is likely that conversions will amount to 20 percent to 50 percent of all new housing in cities.

Three case studies

Calgary

Calgary is a world leader in office conversion. In 2014, its economy began to waver amid a downturn in the oil and gas industry. As those companies downsized and moved, the supporting services that constituted most of the city’s economy did, too, which emptied office buildings. Office vacancy there peaked in 2022 at 34 percent as the C$25 billion Canadian sector shrank to C$9 billion, with significant ramifications for the city’s tax base. Smaller businesses likewise felt the burden as their taxes increased—anywhere from 20 percent to 40 percent—to offset the loss of larger businesses.

Realizing it had to act to stem this decline, the city partnered with the real estate industry to produce the Greater Downtown Plan in 2021. The plan included incentives of C$75 per square foot (0.09 sq m) for office conversions, calculated to be approximately 25 percent–30 percent of the total construction costs, based on projects that were already being planned. This incentive is awarded as a cash payment upon project completion and receipt of an occupancy permit through city, provincial, and federal funding. Money came from Calgary’s “rainy day” fund, which stemmed from any underspending during the last few years. It’s worth noting that Calgary chose to do so because it kept having to give residents and businesses “one-off” tax exemptions every year, which, after five years, became untenable.

Calgary’s downtown has approximately 48 million square feet of office space, of which approximately 17 million square feet (4.5 million sq m) were vacant in 2022. The city’s goal for the incentive program was to reduce the amount of vacant office space by 6 million square feet (560,000 sq m) by 2031. At the time of our interview with Sheryl McMullen, manager of investment and marketing for Calgary’s Downtown Strategy team, 11 projects had been approved, with one complete and another 8 under construction. These conversions are expected to deliver 1,490 homes and 226 hotel rooms.

One of Calgary’s greatest success stories is a building called the Cornerstone, developed by the Astra Group. The 80,000-square-foot (7,400 sq m) building was 100 percent vacant upon purchase in the spring of 2022. The permitting process took only a month because Calgary has no change of use permit requirements, which McMullen estimates to have prevented six months of delays. By October, the company had begun renovations. It was able to complete the project—from purchase to completion of renovations—in little more than a year.

The process is not only quicker than a new build but also cheaper, as well. Maxim Olshevsky, CEO of Astra Group, notes that the major savings were in bypassing the foundation, structure, and elevator costs. He emphasized that the project would not have been possible without the incentive program and the easy permitting process, as their absence would have made the development too risky. The chart below shows where Astra Group spent its money on conversion at Cornerstone. Total conversion costs came to $354 per square foot (0.09 sq m), well below that of a new building.

Above and below: The Cornerstone Building in Calgary was converted by the Astra Group in just one year. Astra Group CEO Maxim Olshevsky notes that the major savings were in bypassing the foundation, structure, and elevator costs. He emphasized that the project would not have been possible without the incentive program and the easy permitting process.

Astra/People First Developments

1 St Clair West

Developer: Slate Asset Management

Location Toronto, Ontario

284,000 square feet (26,000 sq m)

Estimated completion 2024

Originally built in 1968 and pictured above, this office building stands 12 stories tall. Slate Asset Management considered adding 37 stories of residential on top of the existing structure to create a mixed-use building in one of Toronto’s most desirable neighborhoods—Yonge & St. Clair. While this office-to-mixed-use residential conversion is still in the entitlements phase and some of the details are yet to be finalized, Slate’s plan proposes to redesign office floors with new interior partitions and revitalize the ground floor retail and lobby experience. As the original zoning by-law submission describes, the original plan is to keep the elevators, exit stairs, and, if possible, use the existing structure and MEP shaft. Slate will probably have to replace the HVAC system, a cost that varies, based on the local government’s requirements for sustainability measures.

At present, the city of Toronto assumes a 1:1 office replacement in the event of development of redevelopment. Slate’s original application has shown 1:1 office replacement. In recent months, the city of Toronto has lessened this requirement, especially in areas where there are no “in-force” office replacement policies. In a zoning resubmission, Slate is likely to reduce or eliminate the office component, and include an increased residential area, and possibly affordable housing, which reflects most office-to-

residential conversions or redevelopments in Toronto.

As part of the development, Slate plans to retain the precast cladding panels, replacing the existing windows with a mix of high-performance glass and operable units. Windows can significantly affect a project’s bottom line. Renovating a window wall to a curtain wall can make up 15 percent of the hard cost conversion budget in a typical office to residential conversion, according to Veronica Green, a vice president at Slate. The ground-floor windows and new door requirements to revitalize the lobby entrance alone can be exceed CA$100,000. When replacing only the glass, Slate has found that precast Brutalist structures with punched windows are the most cost-effective. The company also plan to introduce ramps on the ground floor for loading and servicing.

Green estimated that a similar new build would cost about C$380 per square foot, whereas conversions can range from C$250 to C$350 per square foot, depending on the façade and the extent of the renovation.

Canada is taking the lead on residential conversions due to the financing offered by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC). It offers attractive premiums and loan amounts for multifamily projects, based on affordability, accessibility, and sustainability, with some loans reaching as high as 95 percent loan to cost ratio. This financing motivates Canadian developers to seek solutions for office conversions, whereas U.S. developers are less incentivized.

Pearlhouse—160 Water Street

Vanbarton Group

New York, New York

Circa 600,000 square feet (56,000 sq m)

Estimated completion 2024

In 2014, when Vanbarton Group bought the tower at 160 Water Street, it had two medical office tenants. The company planned to wait until their leases expired, then renovate the property, which had been built in 1972. Joey Chilelli, Vanbarton’s managing director, emphasizes that not having “a path to vacancy” can be one of the biggest pitfalls in office-to-residential acquisitions. Buying out tenants with long leases may be prohibitively expensive. He cites the reduction in time between construction and lease up as a major factor in these conversions. Once the building was vacated in October 2021, Vanbarton immediately began its demolition process to construct 588 units, undertaking what its personnel believe to be the largest conversion of its kind in New York City history. Because the company bought the building with zoning as-of-right, no approvals were necessary, and the process sped along.

The floor plate of 160 Water Street was deep, with windows existing on only three sides of the building. The core-to-window depth, +/-65 feet, meant that residential units could not be laid out in a traditional way, so Vanbarton’s team members created three large open shafts at the center of the floor plate. In doing so, they were able to remove unusable space, create a zone for a new MEP riser, and later redistribute that removed area to the roof, creating a five-story addition without changing the overall site density. To achieve this outcome, the columns around the new openings were structurally reinforced with plating and new steel cross bracing.

According to Multi-Housing News, in addition to timing, Vanbarton was able to capitalize on two other major advantages that conversions hold over new builds. First, the company was able to achieve a floor area ratio (FAR) close to 20 due to the pre-existing structure’s FAR. Second, at US$650,000–US$750,000 per unit, Vanbarton’s total development costs were low, thanks to the acquisition basis of the aging building and the concomitant reduction in hard costs. Chilelli estimates that these projects usually run US$100–US$200 less per square foot than do new builds of similar quality. Overall, construction costs were US$325–US$350 per square foot, with apartments already renting for about US$90 per square foot. Chilelli estimated that the project could have been done for $300 per square foot, but the final product would have been of lesser quality. Much of the construction cost was in the structural steel, followed by HVAC, MEP, and fixtures and finishes.

Lessons learned

Most of the successful office-to-residential conversions to date are Class B and Class C buildings built in the 1960s and 1970s. These buildings are attractive because they tend to have smaller and more readily adaptable floorplates, and they are cheaper to buy than buildings of later vintage are.

A summary of lessons learned from the interviews and literature appears in Figure 4. Based on its analysis of more than 1,300 buildings, Gensler estimates that approximately 34 percent of office buildings in the United States are convertible. Cities range from 15 percent to 40 percent. Older cities with no downtown street grid system, such as Boston, have fewer viable buildings because fewer of them are rectilinear.

Although office-to-residential conversions will not solve the nation’s affordable housing shortage, they represent an important option for redeveloping a large part of the stock of vacant office buildings. In so doing, they offer a viable approach for reactivating downtowns that are suffering from high vacancies and are restoring the tax bases that have eroded from declining office and commercial values.

Buildings with the wrong shape are impossible to convert. Preferred physical characteristics include the following:

- Window depth ideally is about 35 feet (11 m)

- Floorplate should be narrow to allow for greatest efficiency

- Floor-to-floor height should be at least 9 feet, 8 inches, for a 9-foot ceiling height; typical office

building heights are 11–14 feet - Creativity is essential in figuring out how to get these projects done

Economic considerations

- Time is the biggest factor that makes or breaks conversions. The less time required, the more feasible the project. The reason conversions are feasible to begin with is that they take less time than a new build and can be up to 30 percent–40 percent cheaper.

- Time includes vacating spaces that have existing tenants. 80 percent–85 percent efficiency for conversions is typically feasible, whereas for new builds, it is 75 percent–80 percent

- The more units, the better for efficiency; typically, at least 60 units is desirable.

- Buying the offices cheap is also key to making the conversion pencil out.

- The biggest cost is mechanical, electrical, and plumbing.

- Gensler estimates that conversions typically cost US$300,000- US$350,000/square foot.

Political considerations

Governmental support is needed to make conversions feasible. Support may take several forms:

- Tax incentives (New York City) and other incentives such as additional FAR

- Subsidy (Calgary)

- As-of-right zoning (Calgary); New York just introduced it

- Quick approval process (Calgary)

- Inventory of convertible buildings

- Low-interest loans (Canadian government’s CMHC)

- A wider plan must be in place, with area-specific goals to ensure that buildings are surrounded with uses

compatible with residential.

Further reading: