Slavery and its aftermath were defining experiences for African Americans in the real estate industry, as in wider U.S. society, with bondage, segregation, and racism shaping business opportunities. Despite these impediments, Black Americans have worked as craftspeople, financiers, designers, builders, and developers to contribute to the building of the nation.

The slavery era, “in a very perverse, difficult way,” could be seen as “the most productive” for African American involvement in real estate, says Bradford Grant, a professor of architecture at Howard University in Washington, D.C. He points out that the South was “built on the backs of enslaved African Americans.”

RELATED: Access to Capital: Solutions for Black Developers to Overcome Funding Challenges

For the future of site of Washington, D.C., Benjamin Banneker, a free Black man, was part of the team that surveyed the new capital city. However, many enslaved people worked on the city’s two most symbolic buildings, the U.S. Capitol and the White House. At the National Archives, wage rolls show payments to the enslavers of some of those craftsmen, such as a promissory note for “. . . 1st April to 1st July 1795, 3 Months, at 5 Dollars per Month.”

Throughout the United States, enslaved people shaped the built environment as brick makers, carpenters, plasterers, and more. Hiring out enslaved people to work was commonplace. Although unlikely to have been a widespread practice, in some instances enslaved workers were allowed to keep some of their wages—money that in some cases they used to buy their own freedom.

That was the case for the family of Deryl McKissack, CEO of McKissack & McKissack, an architecture, engineering, and program and construction management firm based in Washington. She is the fifth generation of her family in the business. McKissack’s great-great grandfather, Moses McKissack, came to the United States as an enslaved person, skilled in carpentry and brickmaking, skills he passed to her great-grandfather. Her grandfather and great uncle, among the nation’s first licensed Black architects, designed and built the Alabama airbase that housed the famed Tuskegee Airmen. (McKissack’s twin sister, Cheryl McKissack Daniel, also runs a commercial real estate firm, also called McKissack & McKissack.)

One of Deryl McKissack’s firm’s most prominent jobs was as project manager for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, a landmark building that had about 100 firms involved in its construction.

“It was something I had been planning for a decade,” McKissack says of her firm’s bid for the prime contract on that project, completed in 2016.

As in McKissack’s family, the history of African Americans in commercial real estate breaks down roughly into the slavery era; the post-Civil War Reconstruction and Jim Crow era; the civil rights era, when laws and civic environments shifted; and the ensuing decades.

Stephen Smith, born about 1795 outside Harrisburg, Pa., became a prominent abolitionist and wealthy businessman and real estate owner, but he began life in bondage. As a youth, he worked in a lumber business, and he bought his freedom as young man. He went on to run his own lumber business in Columbia, Pa., a city just north of the Mason-Dixon Line. By 1820, he was one of eight Black people in town who owned property, according to a biography of Smith in a nomination last year for Philadelphia’s register of historic places. He was also a behind-the-scenes banker and the largest stockholder in the Columbia Bank—but unable to be bank president because of his race.

Smith was an antislavery activist, a backer of the Underground Railroad, and the target of racism, including a mob attack on his Columbia business. Around 1840, he moved to Philadelphia, where he continued both his abolitionist work and his real estate business. He was an active real estate speculator, present at just about every property sale; his Philadelphia properties eventually were valued near $500,000, according to University of Texas historian Juliet E.K. Walker, a fortune that made him the wealthiest Black man in the North.

Despite legal and social barriers to property ownership, some African Americans were able use real estate to build their own wealth and help others. Biddy Mason, born into slavery in in the Deep South around 1818, gained her freedom in 1856 in California (a free state) via a judge’s ruling. She used her earnings from midwifery to buy property in downtown Los Angeles. “She carefully studied property market trends, and noted which properties were most desirable; and she ended up owning some of the city’s prime real estate,” wrote historian Marne Campbell of Loyola Marymount University. Mason became well known as a philanthropist, using her money to help individuals and charitable institutions, and funding construction of the First African Methodist Episcopal Church, still one of the city’s most prominent houses of worship.

After the Civil War, some property ownership barriers relaxed, but racism and the rise of Jim Crow laws meant opportunities for African Americans were strictly segregated ones. “The Black churches, universities, businesses, and other organizations were essentially the sole client base, seeking a limited scope of building types,” Howard University’s Grant wrote about opportunities for Black architects from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century.

African Americans made a mark on the built environment, notably in the cities where they migrated from the farms of the post-war South. Although an unknown number of people participated in shaping those cities, some stand out.

Philip Payton, who became known as the “father of Harlem,” was born in 1876 and came to New York City in 1899. He began by managing buildings for white owners in Harlem, steering Black tenants their way. He soon expanded, owned some buildings, and managed others. In 1907, Booker T. Washington called Payton’s Afro-American Realty Company “one of the most interesting and in some respects the most remarkable business enterprise undertaken by Negroes.” Even after that firm folded, Payton went on to more success and bought more buildings. Most of New York’s Black population lived in Harlem by the time of Payton’s death in 1918—just a few years before the blooming of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s.

Halfway across the country, O.W. Gurley, who was born in Alabama in 1868, moved to Tulsa, Okla., around 1905 and purchased land. He started with a boarding house, dubbed the neighborhood Greenwood, and soon built more structures. The neighborhood attracted other African Americans to Tulsa. It soon became a prosperous enclave widely known as “Black Wall Street.” Businesses thrived in its 35 square blocks, and Gurley was a wealthy man.

However, in 1921, mobs of white vigilantes rampaged through Greenwood, burning or otherwise destroying more than 1,200 buildings and murdering hundreds of people; the exact number of victims in what is now called the Tulsa Race Massacre remains unknown. Gurley survived, but his fortune was wiped out. He died in Los Angeles in 1935.

In Chicago, which attracted 500,000 of the 7 million African Americans who took part in the Great Migration, Jesse Binga was a force in developing the South Side. He was born in Detroit in 1865, worked around the country as a barber, and came to Chicago in the 1890s with just $10, he later said.

In time, Binga bought and renovated apartments. In 1908 he opened the Binga Bank, the city’s first Black-owned bank. Eventually he controlled more than 1,000 apartments, and owned swaths of the South Side. Binga was “the money man of the Black Belt,” according to his biographer Don Hayner. “Binga was a symbol of success in the Black Belt, someone who embodied the possibility of the American Dream.” He also was a target of hate. His home and business were bombed eight or nine times, according to the Hayner biography. Binga’s bank collapsed in the Great Depression, and he was convicted of embezzlement.

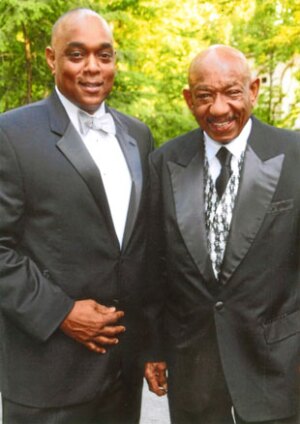

The Depression shaped the attitudes of many Americans, including Herman J. Russell, founder of H.J. Russell & Co., a force in Atlanta construction and real estate for six decades. Russell, who was called “H.J.,” was born in 1930 and grew up in a time when jobs were scarce. As a result, he always wanted to be his own boss. His father, Rogers Russell, was a plasterer. “Plastering was a tough, dirty business,” and so most in the trade were Black, recalls Michael Russell, H.J.’s son and now CEO of the family-owned company.

H.J. learned the trade and built his first rental property, a duplex that brought in enough to pay his college tuition at the Tuskegee Institute, according to the company history.

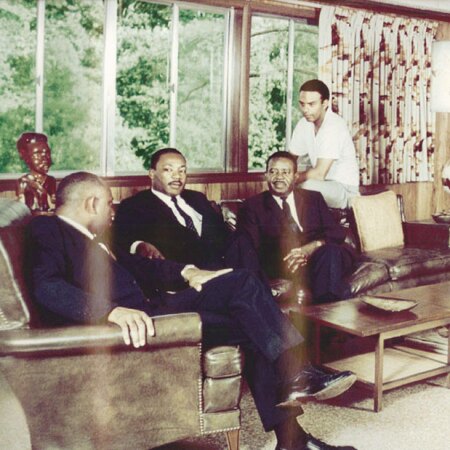

In the 1960s, as the battle for civil rights heated up, Russell was building his construction business, as well as relationships that helped support that business. Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders relaxed at his home. He became the first Black member of the Metro Atlanta Chamber of Commerce—almost by mistake, as his son tells it: “They just sent invitations to potential applicants,” without knowing that the successful builder wasn’t white. By the time of his death in 2014, he was widely lauded as an “Atlanta icon.”

The real estate business “is built on relationships,” Michael Russell says. “Even to this day, it can still be a challenge to African-American firms.” Access to relationships supports access to clients, capital, and workforce, he said.

The Russell company, like its counterparts in other cities, received a boost from civil rights-era federal legislation—including the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968—that aimed to remove legal barriers. Perhaps even more, the company benefited from local rules that required minority-owned subcontractors on city contracts, especially in such cities as Atlanta, which were led by Black mayors.

Even outside Atlanta, relationships built over time count. Russell’s team was one of the firms that worked on the National Museum of African American History and Culture. “That was really relationships,” he says, particularly his family’s connection with John Lewis, the renowned civil rights leader and long-term Georgia congressman. Lewis knew the firm’s background and “relevant experience,” Russell says, with large public buildings.

“Look back on American history,” Russell says. “Look back to slavery. We played an important part in building this country. Through that history, African Americans have shown we have the skill set to execute in the industry.”

History informs the real estate industry now in many ways. “We are sons of the Great Migration,” says Charlton Hamer, senior vice president of Habitat Affordable Group in the Habitat Company, part of a venture developing a residential and retail project in the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago’s South Side.

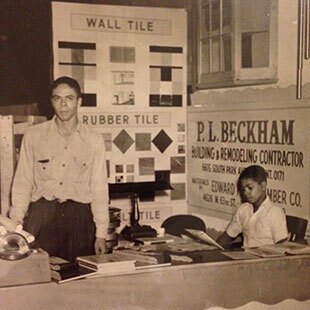

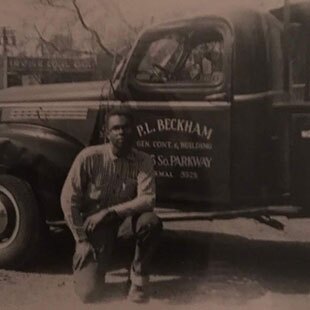

“It’s more than just a development. It’s personal to many people,” says Phillip Beckham, principal of P3 Markets, one of the partners in that venture to develop 43Green. Many recall stories from when the Bronzeville neighborhood was a heart of Chicago’s African American community, back to the 1950s or earlier.

The neighborhood then was “bustling,” Beckham and Hamer say. But as Hamer points out, that was a time of strict segregation, when, out of necessity, “the Black community served its own.” Redlining and other policies kept out investment.

The three-phase 43Green project is estimated to cost $100 million. For the first $40 million phase, which broke ground in January, financing came from a mix of low-income housing tax credits, tax increment financing, and bank loans. “It’s a very layered, very complex capital stack,” which called for significant support from the city, Hamer says.

In that, it’s a far cry from Beckham’s family story. His grandfather, he says, came to Chicago from Alabama and amassed the stake for his construction business through “policy”—Chicago’s illegal numbers game.

Editor’s Note: Originally, published in February 2022, updated in February 2024.