Despite the challenges in finding funding, many experts agree that the benefits ofhaving diverse developers in communities of color and across the entire real estate landscape is critical.

The great divide that prevents Black developers from reaching their full potential is access to capital. They are often competing against generational wealth, expansive real estate development experience, and perception bias, making already-hard-to-secure capital even tougher.

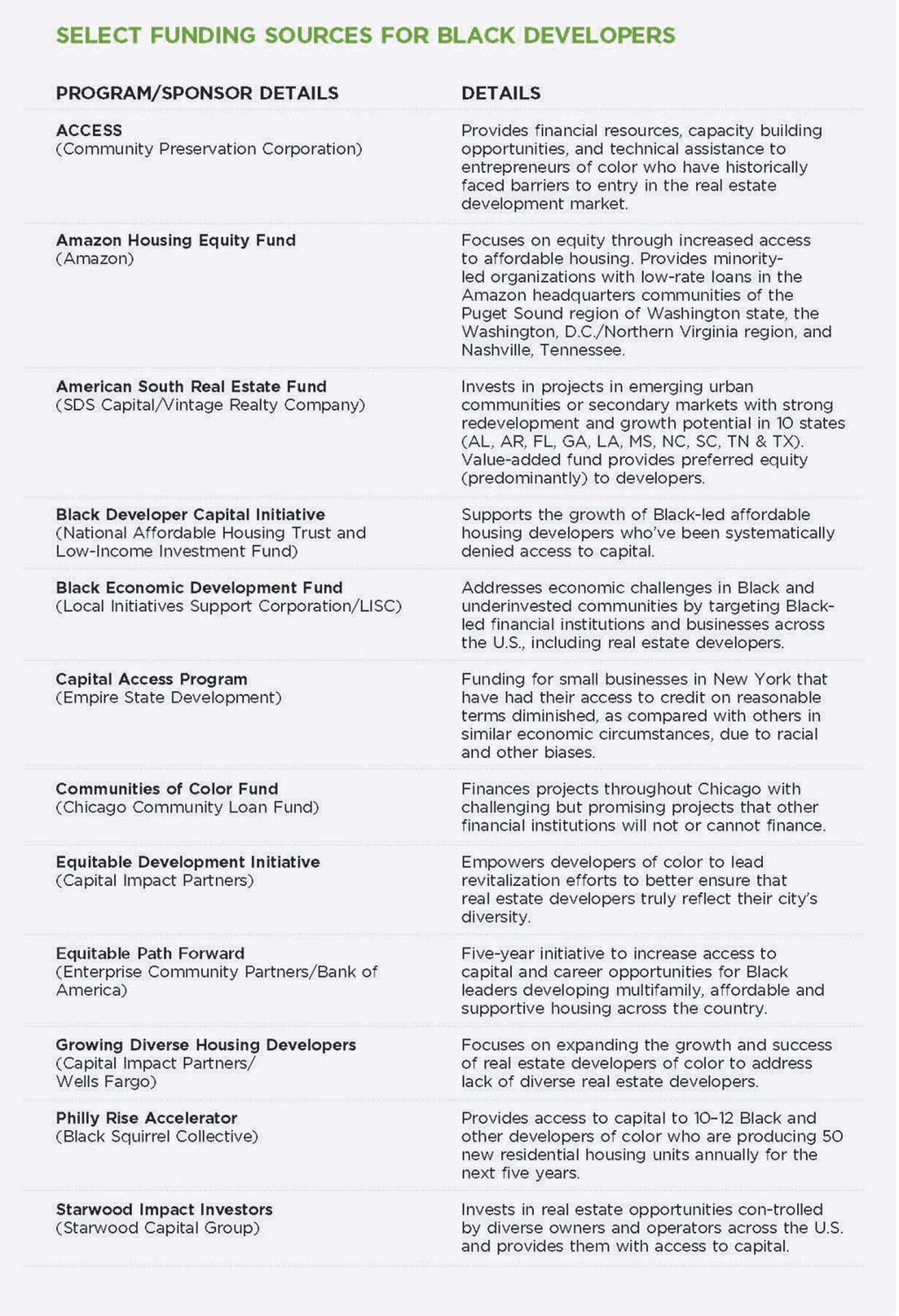

Amid broad acknowledgment of those issues, a growing number of funding sources emerged during the 2020 pandemic, whether from nationally run programs or from smaller state- or community-based initiatives that recognized the disparities and wanted to help fill a void. So far, though, much of the immediate funding has been in the form of debt programs, ones designed as targeted diversity efforts, with predetermined budgets and spending caps, according to Gina Nisbeth, founder and president of 9th & Clinton, a real estate advisory firm in Annapolis, Maryland.

Despite the challenges in finding funding, many experts agree that the benefits of having diverse developers in communities of color and across the entire real estate landscape is critical. “It’s important for people who live in those communities to know that ownership reflects us and their families, [because] we get better outcomes that way,” says Malcolm Johnson, CEO of Langdon Park Capital in Los Angeles.

Johnson worked at one of the largest financial institutions in the country, yet he found out quickly that expertise doesn’t transfer to being respected as a developer. Shifting the lens through which Black developers are viewed and giving them credit for their overall expertise in the industry—instead of dinging them for not having 15 years of development experience—is a must.

“Trying to get capital to understand that our relatively short time in the space doesn’t mean that we don’t have advanced technical skills, it just means that we’ve been sitting at different seats,” Johnson says.

Thomas Webster, chief program officer of Black Squirrel Collective in Philadelphia, recently celebrated the first anniversary of Philly Rise, a five-year real estate accelerator training program to provide access to capital and help level the playing field for Black developers. He says that even when access to capital is given to diverse developers, they’re paying a higher premium, because they don’t have the same experience or their projects aren’t as profitable, all of which becomes a cycle.

“They also have to make sure that they account for every penny, which means they have to watch every dollar,” he says, adding that any setback translates to losing money. Webster notes that Philly Rise provides 85 percent of the debt, and it’s coming in at a reasonable cost of capital, which automatically means the project is going to be more profitable.

Tyrone Rachal, founder and CEO of Urban Key Capital Partners in Atlanta, says that, in the early stages of a project, there needs to be patient equity capital from institutions which understand his community. “We assume that BIPOC developers are just investing in our communities, which tend to be distressed, and have even higher hurdles for attracting traditional capital, so [even that] exacerbates the issue,” he explains.

Equity possible

Ask Black developers about funding challenges and they all agree that raising equity is especially difficult. Michael Collins of Grayson Capital in Kansas City, Missouri, says that debt thinks much differently than equity does. “Raising equity is always difficult, and when you add the component of color, we have to do a little bit more, so we’re always anticipating a no,” he says.

Collins believes that many financial institutions don’t understand how specific submarkets work, to the point that they’re unsure of how to even underwrite deals in some areas. It’s difficult to get equity in your corner to underwrite the deal when [investors] don’t believe the economic returns will be in their favor, once you sell the assets. “If you talk to private equity in certain markets in higher-end districts, they just don’t know the economics, and what you don’t know, you fear,” Collins says. Thus, don’t go into it looking for equity unless you have a deal.

Urban Key Capital Partners’ Rachal uses two neighborhoods in Atlanta as an example and notes that investing in the affluent Buckhead community is different from investing in the community of Bankhead.

However, there are grant programs that sometimes offer capital for predevelopment dollars, which Collete English Dixon, executive director of the Marshall Bennett Institute of Real Estate at Roosevelt University in Chicago, says are sometimes a part of that equity contribution that’s needed.

Deborah La Franchi, founder and CEO of SDS Capital Group in LA, says that most real estate funds exceed a billion dollars, so if you’re just starting out and need $3 million to $5 million in equity for a project costing $10 million to $20 million, none of the big funds will even look at you.

La Franchi’s firm has money available to smaller developers. For example, SDS Capital provided New Orleans–based developer VPG with $2.7 million of preferred equity for a project whose cost was just under $20 million. “That was [small, even] for us, frankly,” she says. “But it was a really talented team [whose founders] all came out of Tuskegee University with engineering degrees and wanted to have their own company. We hope to keep funding them year after year to help them grow.”

The extremely high cost of capital inhibits the possibility for Black developers’ projects. “For example, the capital may be needed at a low interest rate as equity or be structured as a soft loan from cash flows, or as predevelopment capital,” says Rachal. “These are terms that are not available, but [they are] most needed.” Of the trillions of dollars in private equity capital available in the market for real estate investment, less than 1.7 percent goes to Black, brown, or women developers, he notes.

Jeff Mosley, director of Capital Impact Partners National Equitable Development Initiative, points out that many communities of color have been systemically undervalued, and that although equity capital is hard to get, often even the debt capital comes with issues. “We often hear from our developers that sometimes the debt capital is there, but it may not be [at] the rates and terms that are useful for our developers.”

Furthermore, although post-pandemic accessibility to funding sources for diverse real estate developers increased in the short-term, it falls significantly short of the need and has not addressed the systemic barriers that prevent developers from accessing capital which was already in the market, particularly for equity, says Nisbeth of 9th & Clinton.

Different risk assessment rules

Black developers are also wary of their risks being unfairly assessed. “Our loans are always put through the wringer and heavily scrutinized and evaluated, and reevaluated, and then re-evaluated again,” says Derrick Tillman of Bridging the Gap Development in Pittsburgh. Knowing that such risk will be assessed differently, means that these developers face the pressure of having to present an almost perfect deal, he adds.

This aspect of the process is counterintuitive, because most minority business enterprises don’t come from generational wealth, so the required guaranty and strong balance sheets don’t meet the guarantee or net worth requirements. Tillman says that instead of building a reserve or having a separate fund to meet those guidelines, diverse developers get overassessed and steered toward more programs, when what they really need is access to capital to help bridge the gap.

Collins served as the managing director of a private equity group. The questions he gets asked today differ from what he was asked then, he says, and he credits that shift to the infrastructure he now has behind him. Sometimes, getting equity in your corner to underwrite deals can be difficult, because there are so many risks—associated and unmitigated risks—and your equity pool starts to dwindle. If you don’t already have a relationship with equity, gaining one is going to be much more difficult, because you have to get their buy-in for lenders to trust you. “It’s really about how they like you and if they believe you can manage their money in the right format,” he says.

Nisbeth doesn’t think risks are necessarily assessed differently, so to speak. She maintains, instead, that the market has created measurements of risk which are rooted in class and race and, thus, is unsure whether data supports such perceived risk. Nisbeth says, “I also do not know if the market has any incentive to change this [reality]. The current measurement of risk benefits those who have made the rule. More data may help.”

Low-income housing stigma

Another issue involves all diverse developers being pigeonholed into one type of development. Collins explains that, just because you’re a person of color, it doesn’t always mean you’re exclusively focused on attainable or affordable low-income housing. Often, Black developers are put in a different category, such as impact capital, which leads to a different set of questions. “It’s a stigma that we all … look at the same types of development, and if we don’t do low-income housing, then there’s no reason to look at the deal,” Collins says, adding that we also shouldn’t assume that there’s not wealth in historically Black areas. “We have to understand that market, as well as the markets that are not of color, because we want to move within both of them.”

Nisbeth echoes that message and says there’s an evident lack of diverse real estate developers in certain markets. Much of the effort to increase diversity in the industry has been narrowly focused on the affordable housing market “to the exclusion of other market sectors that can be more financially lucrative,” she says.

Funding programs changing the narrative

Although the developer landscape is becoming more diverse every day, Nisbeth says the number of programs and associated dollars put toward this historic problem pales in comparison to what is needed to solve it. Johnson, however, says that the message is gaining traction, with a lot of institutions saying they want a more diverse group of borrowers and investor managers because the returns from what Black developers are doing tend to be strong.

Mosley says his Growing Diverse Housing Developers program was awarded $30 million by Wells Fargo in 2021 to work with 27 diverse developers across the country who are more established in the space.

Wells Fargo’s goals are to increase the supply of homes that are available and make sure that the development firms have the capacity to attract enough capital from other sources in the space. The goal is to develop 1,500 affordable housing units nationwide over four years.

It’s important for banks to look at their credit box, determine who is not represented in those deals, and find prudent ways to be more flexible with developers of color. “What financial institutions can do is understand that getting a project off the ground requires a level of capital that is more at risk,” Mosley says, adding that the program has created a loan product to specifically help fund the early-stage, high-risk capital to help these developers progress.

In addition to creating a national learning cohort of developers who meet monthly, the program makes sizable enterprise-level grants into these organizations so that they have the foundation to grow and the equity necessary to make them competitive, while ensuring that they have full control of whatever project they’re pursuing.

To be able to help create wealth among people in a historically excluded group that has not had a seat at the table due to systemic and institutional racism is a game changer, says Kareem Thomas, chief credit officer at the Wells Fargo–backed Reinvestment Fund in Atlanta. “The Reinvestment Fund has also been intentional with enhancing our credit policies and underwriting guidelines to ensure we eliminate any perceived barriers to accessing capital,” he says.

In some instances, Tillman says, things are getting better as few lenders or Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs)—or both—are offering funding responsive to the specific needs of diverse developers. But he said more needs to be done to help them scale their offerings.

Black Squirrel’s Webster says that another similarly sized and experienced developer may be more profitable because the capital made available to them comes at a more affordable rate. “Therefore, I’m hindered, and that’s held against me until I hit a certain stage.” To have access to much more is why government programs are being created to support under-represented developers who are working in distressed neighborhoods. “They have to have the access to much more affordable and reasonable money,” he says.

But Tillman maintains it’s important to note that not all CDFIs are created equal, and some are more conservative than banks.

Bank of America, in partnership with Enterprise Community Partners, is investing $60 million—$30 million in loans and $30 million in equity financing—to support Enterprise’s Equitable Path Forward, a five-year initiative to help facilitate racial equality in housing. The investment is anticipated to increase access to capital and career opportunities for Black developers.

Financial institutions are not alone in looking to make a difference; religious organizations also recognize the need. Pastor Matthew Watley of Kingdom Fellowship AME Church in Calverton, Maryland, believes that, because Black churches are the largest owners of property in Black communities nationwide, the church should have a hand in creating generational wealth and improving communities of color.

Watley teaches his congregation how to acquire commercial real estate. It’s not just talk. According to his representatives, he has acquired $27 million in commercial property for the church, which also owns and operates a 125,000-square-foot (11,600 sq m) tower that it leases primarily to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, among other businesses.

Words of advice

Tillman suggests that Black and brown developers maintain another source of income until they amass enough units or development projects that produce a significant cash flow and build operational capital into all the project budgets. “Focus on developing in communities that are MBE [minority business enterprise] developer–friendly, where the city and/or state understands [it has] a role to play in advancing this issue,” he says, adding that as you prioritize working in these communities, ensure that they have taken that role seriously and put major staff resources and capital resources behind their statements that this outcome is a priority.

“Build relationships, ask questions, and ask for mentors,” says Collins, who adds that it’s okay to have advisers who don’t look like you, but one who speaks to the deal and understands the marketplace adds credence.

Being a developer is the riskiest part of the real estate spectrum, with the most money at risk, longest time frame, and the most issues, says English Dixon, adding, “If you want to be a developer, recognize that you have to build the skills and the box of credibility and capital.”

It’s also a numbers game: the more you have to show, the better your odds. Rachal says that once you have five deals under your belt, it gets easier to talk to financial sources, because you’ve already established a relationship with them.

Developers and financial institutions agree that building relationships is key. La Franchi suggests looking up active equity funds and calling them. “Also reach out to other developers of the same scale and get their advice, ask how they raised equity on their first deal,” she says.

When it comes to banks and investors, Mosley says they should recognize as both an opportunity and a responsibility that sound developments are created by developers of color who are going to have an impact on communities.

CARISA CHAPPELL is a digital content editor with S&P Global Ratings, based in Chicago.