Top-down construction—constructing floors at ground level, then raising them to the top of the building and then successively downward—potentially offers an attractive alternative to conventional construction, with its costly, labor-intensive, and environmentally wasteful process of building steel frames, floors, walls, and all components of a building at height. But adoption of an advanced form of top-down construction has not become widespread.

With recent refinements, however, top-down construction has become a much more practical option. Under current commercial real estate business conditions—namely, soaring construction costs, labor scarcity, and environmental degradation—the cost savings, labor reduction, and enhanced sustainability of this approach have become even more compelling for the commercial real estate industry.

The Termohlen-Thornton Concept

Architect’s conception: A north view of eVolve Towers, located in Denver, Colorado, currently under development by Ubuntu Partners. Top-down construction involves the construction of individual floors at ground level by tradespeople, then raising successive constructed floors by hydraulic heavy-duty jacks starting at the top floor of the building and going floor by floor to the lowest floor. The two-tower apartment complex is TGE Top Down’s first top-down project in the United States, after completing two laboratory/office towers in Bangalore, India. (Dan Esparza)

The Termohlen-Thornton method was invented in 1973 when the now-retired founder and former chairman of the renowned Thornton Tomasetti structural engineering firm, Charles H. Thornton, joined forces with “suspended building construction” top-down construction system inventor David Termohlen. Thornton quickly became a convert to the virtues of the Termohlen-patented method after completion of half a dozen buildings using top-down construction.

Widespread adoption of the Termohlen-Thornton top-down construction method was delayed until Thornton retired as chairman of Thornton Tomasetti in 2004 and founded TGE Top Down with Jeff Grillo, an owner’s executive, and Dan Esparza, a contractor and veteran industry entrepreneur. Often confused with lift slab construction—which infamously caused the collapse of L’Ambiance Plaza in Bridgeport, Connecticut, in 1987, killing 28 construction workers—the advanced Thornton top-down method is completely unrelated.

The result of 45 years of research, TGE’s construction process comprises the following key elements:

Central cores/spines to support the top-down construction, including elevators, stairwells, and major utilities, are erected first.

Tradespeople construct each floor, including everything that will be located on that floor, at no more than six feet (1.8 m) above ground level.

Heavy-duty hydraulic jacks, staged on the ground with a pulley system at the top of the cores, spaced out at relatively few intervals beneath the periphery of each respective floor, raise the completed floor to the level where it is to be attached to the core.

At the same time as the jacks raise each floor, tradespeople construct the next floor, including everything that will be located on the floor, to save time, which can be done safely because of redundancies built into the jacks.

Extremely strong steel bars retracted into the initially erected cores are pushed out from the cores and then inserted into holes at the periphery of each floor to provide the structural support for each, and then bolted into place as permanent supports for that cantilevered floor.

This process is repeated for each floor until all of the floors are in place.

Saving Time and Money

Between 2017 and 2018, TGE completed a total program of 1.2 million square feet (111,500 sq m) in Bangalore, India. The program consisted of two identical buildings for Intel Corporation—the first use of advanced top-down construction since the last use of the Termohlen system in the 1970s. Each building was planned to measure 624,000 gross square feet (58,000 sq m), take 36 months to construct, and cost $200 million.

Together, the two buildings came in jointly for a total of 38 months and $244 million, a significant improvement over the 72 months and $400 million originally projected.

In 2017, Thornton and TGE Top Down licensed their top-down system to another general contractor, LIFTbuild, a subsidiary of Detroit-area construction firm Barton Malow, which uses manufacturing processes to create and lift-to-place to make a tight Detroit site a better fit. LIFTbuild recently completed a 16-story tower called The Exchange, a $64.6 million building in Detroit’s Greektown neighborhood. The tower comprises 153 residential rental units, 12 condominium units, and 166,000 square feet (15,400 sq m) of ground-floor retail space.

The site is tight because it is triangular and measures only three-quarters of an acre (0.3 ha). It is surrounded on all sides by busy streets and businesses, making traditional construction impossible. In addition, the elevated Detroit People Mover, located at the edge of the site, precludes any potential use of tower cranes—and top-down construction eliminates the need for them. The core structure of the top-down method supports the cantilevered floors from the middle core rather than from steel frames at the edges of the site, concentrating construction away from the site’s boundaries and facilitating construction on the small, irregular site.

The Exchange is Greektown’s first residential development in 60 years. LIFTBuild is acting both as a general contractor and a development partner. In January, LIFTbuild completed raising all the floors at The Exchange.

More Top Down Going Up

TGE Top Down and Ubuntu Partners Real Estate, a developer based in Denver, are in the design phase of TGE’s first project in the United States, eVolve, in Denver. Located in the Arapahoe Square District, eVolve lies 10 blocks north of the City and County of Denver Government Center.

Ubuntu Partners is acting as a merchant builder of eVolve and will immediately sell it to Evolve Development Holdings LLC. Ubuntu Partners’ managing partner Karina Christensen says that despite easy access via a major highway and robust surrounding redevelopment, the site on which Ubuntu acquired to develop eVolve was in a moribund area of relatively nondescript blocky buildings.

According to Christensen, Ubuntu saw an opportunity to do something truly extraordinary at this location and hired a Barcelona architect with Catalan aesthetic sensibilities to design eVolve. The exterior design sports shapely curves, with a U-shaped rather than a block footprint, and two 19-story towers on either leg of the U—one with apartments, the other with a luxury boutique hotel. Avant-garde interiors style a European motif with smartly designed living spaces.

All told, with ground-level retail uses and four stories of above-grade parking, eVolve comes in at just shy of 400,000 square feet (36,200 sq m) with an expected construction cost of $122 million.

During the initial design phase, eVolve did not pencil out financially with two towers largely because of the U-shaped rather than block footprint, Christensen says. Then, Ubuntu heard about top-down construction and the major cost savings it generates, recognizing that it represented “a paradigm shift for construction that saves so much material,” and the partners knew they had to use it. Six months into the design phase, they changed from traditional to top-down construction, slashed eVolve’s cost, and only then did eVolve pencil out with both towers.

“We came in about 25 percent less expensive than a high-rise, cast-in-place, flat-plate concrete project,” Thornton says of eVolve.

Thornton and Esparza say that, like their firm’s Bangalore top-down buildings, the design and structural engineering of both eVolve towers feature cores that support cantilevered floors.

“We’ve got our vertical supply chain involved with the project,” Esparza says. Delivery of everything ranging from the curtain wall to mechanical, electric, and plumbing systems will be done using TGE Top Down’s manufacturing process-enabled supply chain. “The eVolve project has been in the making for three years. Right now, we’re in the site development plan amendment phase, together with an early design development concurrent path.”

TGE plans to break ground for eVolve by the third quarter of 2023, depending on the firm’s ability to pull permits.

Given that Ubuntu is a merchant builder, eVolve’s buyer, Evolve Development Holdings LLC, just secured senior debt financing for eVolve that includes a bond issuance and covered most of the costs associated with the project. Mezzanine financing also was used to bridge the gap between the senior debt and the equity. The equity financing was a mix of developer equity and property assessed clean energy (PACE) equity funding. Of importance, the top-down building process did not affect the financing structure of the eVolve project.

Many would think that a new technique like top down would be more expensive to insure than traditional construction, but in part because TGE is collaborating with insurance giants Aon and Arthur J. Gallagher & Co., insurance companies understand that top down reduces many risks and thus underwrite top-down construction insurance at lower rates than traditional construction. Costs of wrap-up/workers compensation/employer liability, construction/builder’s risk, default, general liability, defect, and cost overrun/liquidated damages insurance are all reduced.

Accelerating Top Down

In the current economic environment, top-down construction is a hedge against both the high cost of construction materials—since it reduces the quantity of construction materials needed and thus their overall cost—and also the scarcity of labor, since a top-down project uses fewer construction workers.

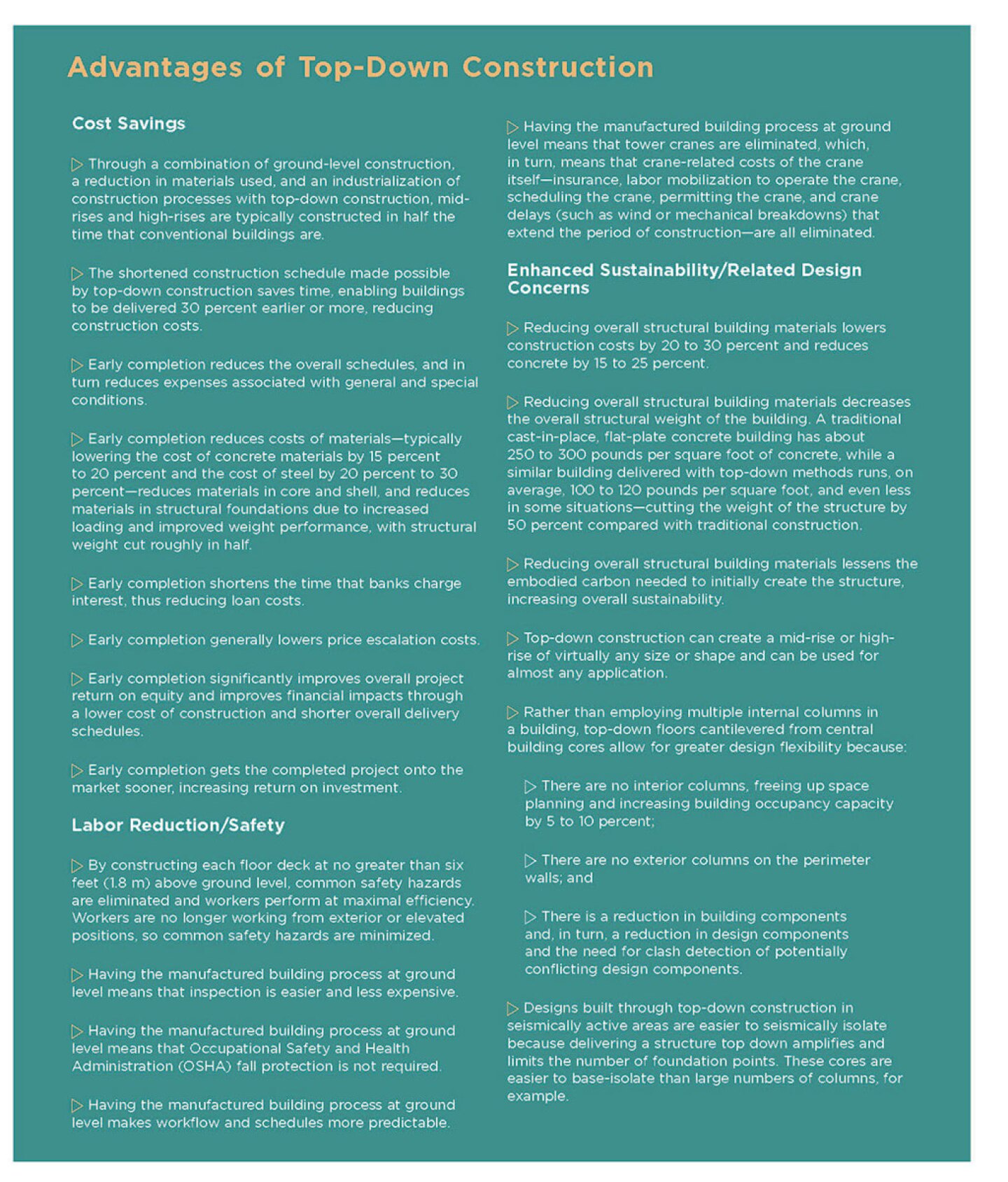

As detailed in the “Advantages” sidebar, the benefits of top down are significant and even revolutionary.By saving so much on construction, top down makes feasible those development projects that would not have penciled out using traditional construction, as eVolve illustrates. While the efficiency of top down may reduce the number of workers on a given project, the cost savings of top down will enable the development of more projects, which will increase the number of construction workers.

Switching costs in shifting construction methods from traditional to top down seems to be the main barrier to implementing top-down construction on an industrywide basis. Given the scale of the advantages of top down, the payback period of amortizing switching costs should be relatively short.

Resistance to an unfamiliar innovation is to be expected. But as leading construction executives fully learn about the advantages of top down, they are coming around, barriers are being broken down, and they frequently become converts as Thornton did, with top-down construction innovation becoming more accepted by all stakeholders.