At a concurrent session at ULI’s Virtual Spring Meeting, speakers made the business case for the importance of considering embodied carbon during development and construction, as well as explored how cities are creating policies to address embodied carbon and how real estate organizations have already started reducing carbon emissions.

“It is the new frontier in the world of green buildings,” said panelist Natalie Teear, senior vice president of innovation, sustainability, and social impact at Hudson Pacific Properties.

Clockwise from upper left: Dominique Hargreaves, deputy chief sustainability officer for the city of Los Angeles; Natalie Teear, senior vice president of innovation, sustainability, and social impact at Hudson Pacific Properties.; panel moderator Marta Schantz, senior vice president of the ULI Greenprint Center for Building Performance; and Jill Ziegler, director of sustainability at Brookfield, presenting at the 2021 ULI Virtual Spring Meeting.

Embodied carbon—the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions attributed to the manufacture and transport of construction materials, the process of construction, and building disposal—accounts for about 11 percent of global emissions. These emissions come primarily from a building’s structural system, including concrete, steel, and synthetic insulation.

“This upfront embodied carbon cannot be reduced in materials once a building’s construction is complete,” noted panel moderator Marta Schantz, senior vice president of the ULI Greenprint Center for Building Performance. With that in mind, leading developers are beginning to incorporate cost-effective considerations regarding embodied carbon during project design and setting standards across their development portfolios.

Using Data to Set Embodied Carbon Baselines

For Hudson Pacific Properties, sustainability investments create a positive feedback loop resulting in lease renewals and higher rents, and they contribute to a higher asset value. For those reasons, Hudson Pacific has made a commitment to net-zero carbon, achieving net zero scopes 1 and 2 emissions (operational emissions from the building owner and tenant) in 2020. However, because Hudson Pacific also develops new buildings, operational emissions are only a part of its total carbon footprint. Now, Hudson Pacific is shifting its focus to tackle the embodied carbon footprint.

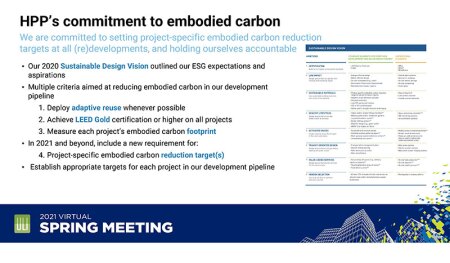

While the industry is still early in the process of quantifying the environmental impacts of building materials, Hudson Pacific is already identifying the right points in the building life cycle to consider embodied carbon. The firm created a Sustainable Design Vision that outlines environmental, social, and governance (ESG) expectations and aspirations for all projects.

To help projects reduce embodied carbon, criteria in this vision include employing adaptive use wherever possible, achieving Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Gold certification or higher, and measuring each project’s embodied carbon footprint.

“We realized we couldn’t set targets or develop a program if we didn’t know where we were,” Teear said. “We’ve spent the last year and a half really focused on building the baseline and understanding our data.” In 2021, Hudson Pacific has also added the requirements to establish a project-specific target for embodied carbon, track progress, and report publicly over time. While Hudson Pacific is still testing measurement tools and streamlining processes, the project teams, including partners, are building their vocabulary and familiarity with the topic.

One example is an adaptive use project in Los Angeles—redeveloping the former Westside Pavilion mall as a state-of-the-art campus for Google. “We retained all of the structural steel of the building, and when we used EC3 [the Embodied Carbon in Construction Calculator benchmarking and assessment tool] and did some backwards-looking calculations, we found that by saving that steel and reusing it, our embodied carbon is 33 percent lower than it would have been otherwise if we had just demolished the whole thing and built it from the ground up,” Teear said.

Hudson Pacific is not just looking at the embodied carbon of building structures. At the Bentall Centre in the central business district of Vancouver, British Columbia, the company is assessing embodied carbon involved in repositioning the current buildings, designing a new building, and building out a new regional office.

For the new regional office, Hudson Pacific completed its first embodied carbon assessment of an interior project, identifying quick wins where carbon was reduced at zero cost. For example, simply switching the types of carpet tiles saved five metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. Using these lessons learned, Hudson Pacific has created the “Low-Embodied Carbon Tenant Fit-Out Guide” for Vancouver and is working to share the findings more broadly across the portfolio.

At one 300,000-square-foot (28,000 sq m) development project in San Francisco (currently delayed by COVID-19), a cross-laminated timber (CLT) structure was considered as a market differentiator with the potential to attract large tech tenants with advanced sustainability requirements. A full life-cycle analysis showed that compared with a traditional steel structure, CLT reduced global warming potential by 6.7 percent (not including biogenic carbon or carbon that can be sequestered). That reduction could be improved because the CLT Brookfield planned to use came from Europe and had a higher embodied carbon impact due to transportation.

“That’s a lesson we’ve learned for the future, said panelist Jill Ziegler, director of sustainability at Brookfield. “We need to get ahead of that before those decisions were made.”

For a high-rise multifamily building in Los Angeles, the structural engineer requested environmental product declarations (EPDs) at the same time it requested the pricing information. While EPDs were not readily available and were not used to make the selection, Brookfield did require its suppliers to eventually create EPDs.

“Hopefully, because we asked the question in the L.A. market, it means that other projects can take advantage of the transparency that we asked for,” Ziegler said. And setting a common embodied carbon goal and asking all vendors—such as the design team and concrete supplier—to work toward that goal instead of telling them how to meet it made a huge difference, she said. In total, the project achieved a 24 percent reduction in embodied carbon, primarily by tweaking the concrete mix, at a zero cost premium.

The Public-Sector Perspective

A major driver for real estate organizations starting to think about embodied carbon is the potential for local regulations. In Los Angeles, the Sustainable City pLAn addresses Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions and specifically addresses buildings, setting targets for energy efficiency and GHG reductions.

Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti is the chair of C40, a consortium of 97 of the world’s largest cities committed to upholding the Paris Agreement on climate change. In accordance with that accord, Los Angeles is aligned with the organization’s Net Zero Carbon Buildings Declaration, which states that by 2030 all new construction in the city will be net-zero carbon, and that by 2050 all buildings (more than 1 million currently exist) will be net-zero carbon. Because two-thirds of the city’s existing buildings are projected to still be standing in 2050, a large potential exists for adaptive use, which can support the city’s climate goals.

“As we zero out carbon from operations, we need to be focusing on embodied carbon,” said Dominique Hargreaves, deputy chief sustainability officer for the city of Los Angeles.

The next step is the Clean Construction Declaration, she said. Layered on top of the city’s net-zero carbon commitment, the declaration has three main tenets: reduce embodied carbon by 50 percent in new construction and major renovation projects by 2030, reduce embodied carbon by 50 percent for infrastructure projects by 2030, and require use of electric construction equipment by 2025, as well as eliminate emissions on construction sites by 2030.

“Achieving these very ambitious aims requires a road map, and planning and consultation with developers, with contractors, with the whole supply chain to see this through,” Hargreaves said.

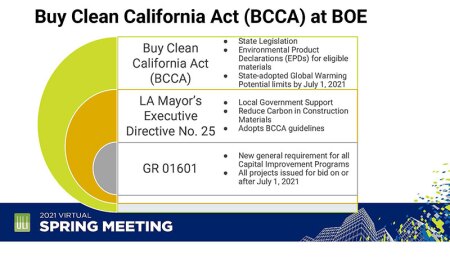

For city operations, the mayor’s Executive Directive No. 25 adopted the Buy Clean California Act, which mandates EPDs for certain materials and sets global warming potential limits on materials for all projects using city funds, including infrastructure and university development. With the U.S. Congress considering major infrastructure investments, potential funds coming to the city for infrastructure projects will be beholden to these new standards. As many of these policies come into effect this year, Los Angeles is working to raise awareness and educate staff and the market on the new requirements and how they will be enforced.

Integrating Embodied Carbon into Business as Usual

During the moderated discussion, panelists highlighted the importance of staying ahead of the regulatory curve, keeping an eye on markets with new policies and those considering policies, and determining how baselines are quantified. They also called for more collaboration across the industry to standardize requests to suppliers and show market demand for low-embodied-carbon materials.

However, it is still important not to forget the basics, Ziegler said. “If you make your processes and designs more efficient from the start, you can measure that and have a big waste reduction and carbon reduction impact without even going to all these detailed scientific tools,” she said. “I just want to remind everybody you can start there.”