The global real estate industry is increasingly committed to reducing carbon emissions, improving operational efficiencies, and incorporating on-site renewable energy. In parallel, municipalities also are showing leadership in adopting new climate mitigation policies to further push the built environment to meet the climate change challenge. But awareness is increasing of another carbon emissions culprit in the built environment: embodied carbon.

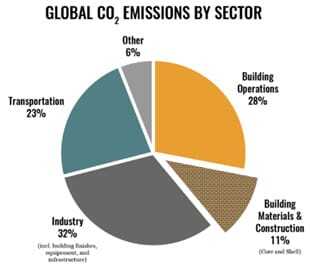

Embodied carbon refers to the emissions associated with manufacturing, transportation, and construction of building materials, as well as building disposal. Embodied carbon in buildings accounts for an estimated 11 percent of total global greenhouse gas emissions. As buildings become more efficient and emit less carbon during their operational lifetime, embodied carbon will become the majority share of building-related carbon emissions.

Reducing embodied carbon in building materials is more complex than the green building industry’s initial campaign to reduce carbon emissions through operational efficiency, both in terms of the implementation and the business case for doing so. With building structural components like concrete and steel up to 80 percent of a building’s embodied carbon, embodied carbon reductions are primarily made during the design and construction phase of a project.

The ULI Greenprint Center for Building Performance’s recently released primer on Embodied Carbon: Carbon in Building Materials for Real Estate is meant to prepare the real estate market for a low-carbon materials future, making the business case for why real estate should pay attention, highlighting smart steps to reduce embodied carbon, and showcasing peers already addressing the issue. To learn more, download the resource at uli.org/embodiedcarbon.

All these challenges create newopportunities for real estate developers, architects, contractors, andengineers to add value to their projects by pursuing embodied carbon reductions.Staying ahead of regulatory pressures by adopting and adapting early on willdetermine success and cost feasibility of low-embodied carbon construction downthe road. The business case for reducing it is already growing:

- Designs that use fewer materials automaticallysave on the costs of materials. Many low-carbon materials are alsoprice-neutral, or in the case of materials like mass timber, provide costsavings elsewhere by lowering labor needs and speeding up the construction timeline.

- Building codes and legislation at both the localand national levels are starting to regulate embodied carbon in development. ManyEuropean countries now mandate preliminary embodied carbon benchmarking forconstruction projects, and laws like Buy Clean California include similarmandates for state-funded projects.

- For those buildings looking to achieve greenbuilding certifications like Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED),Building Researchment Establishment Environmental Assessment method (BREEAM),or the Living Building Challenge, projects that incorporate material reuse,low-carbon material use, and embodied carbon calculations are rewarded withpoints toward certification. Voluntary reporting and disclosure initiativeslike CDP also are beginning to request information on embodied carbon.

- Cities globally are looking for ways to reachaggressive carbon reduction goals and often reward developers for incorporatingsustainability into design and development decisions. Developers who showmunicipalities and community-based organizations that they are drivingadvancements in deep carbon reductions gain community goodwill by aligningtheir goals with city stakeholders.

Projects worldwide have begun incorporating embodied carbonconsiderations into the development process by engineering structures moreefficiently so that fewer materials are needed to construct the supportingframework for the rest of the building, or designing out excessive materialsuse, such as floor and ceiling finishes that are wanted rather than needed. Notall necessary carbon reductions can be achieved through creative innovation indesign, though, so choosing specific materials wisely is a key component toreducing embodied carbon in buildings.

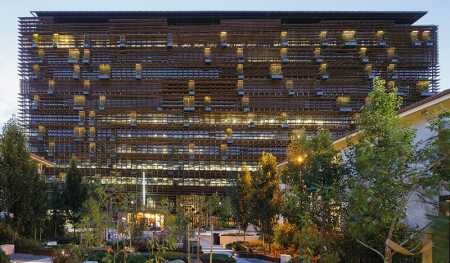

A notable example of using low-carbon materials in real estate development is the Nishi Building in Canberra, Australia, which balances sustainability with human-focused design, and provides a mixed-use development, including 233,653 square feet (21,700 sq m) of multifamily residential space and 524,442 square feet (48,700 sq m) of commercial space, office space, a hotel, retail, and a movie theater. The puzzle-like Nishi Building complex is the brain-child of Molonglo Group, a diversified Australian property developer and design firm. The use of sustainable materials was nonnegotiable to Molonglo and mandated early when working with its suppliers and contractors. Examples of these materials included the following:

- 100 percent GreenStar–rated concrete, an international standard, which uses a higherproportion of recycled materials.

- Sustainably harvested timber from regional blackbuttgum trees measuring 131 feet (40 km) in length.

- Reclaimed timber—the entryway alone used more than2,000 pieces of reclaimed timber.

- Art installations made from 85 percent repurposed constructionwaste, recycled and diverted from landfills.

By outliningsustainability principles from the outset of a project, Molonglo saw deepcarbon reductions without drastic financial sacrifice. Investment in low-carbonmaterials and design that communicates higher value to the tenant, and happytenants are also more valuable to a building owner, either through fasterlease-up, lower turnover, or a higher willingness to pay. According to NikosKalogeropoulos, director at Molonglo, “Often, buildings are too focused ondesign and forget the human element. People want to live and work in buildingsthat are sustainable, promote social cohesion and well-being, and provideaccess to amenities and value when extra time and care have been taken. If youplan for it, the economics works out.”

With the help of capable, experienced construction teams,developers can often build new properties with much lower embodied carbon in buildingmaterials at no to minimal incremental cost. Fortunately, finding ways toreduce embodied carbon through design, engineering, and material choices isbecoming increasingly easy to do. Calculator tools for analysis, and low-carbonmaterials for supplies, are growing in popularity and presence in the industry.The University of Washington’s CarbonLeadership Forum and , Architecture2030,materialsCAN,and WoodWorks all have free andaccessible information and training on embodied carbon in real estate.

In collaboration with other industry leaders, the Carbon Leadership Forum will be releasing an open-access Embodied Carbon Calculator for Construction (EC3) tool to help building industry professionals benchmark embodied carbon as well as perform cross-comparisons of different materials to understand their carbon intensity. This tool has already received industry attention. Alexandria Real Estate Equities (Alexandria), a real estate investment trust that owns, operates, and develops sustainable and collaborative life science campuses, is one of the first commercial real estate companies involved in the tool’s pilot program. While Alexandria has already set a 30 percent operational carbon pollution reduction goal from 2015 to 2025, the company also recognizes that buildings under construction represent a significant opportunity for additional carbon pollution reduction. Alexandria aims to raise awareness of the issue by demonstrating an early commitment to reducing embodied carbon. Alexandria will use the EC3 tool on development and redevelopment projects going forward, establishing quantitative metrics and measuring carbon reductions based on the latest research.