Developers and buyers create new models for housing that hold the promise of a more environmentally friendly, connected, and multigenerational way of living.

This article was published in the Spring 2023 Issue of Urban Land.

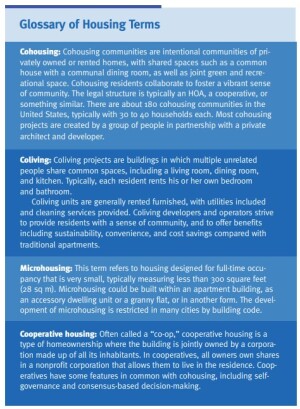

Cohousing joins coliving, microhousing, accessory dwelling units, and other housing innovations that are meeting the evolving needs of individuals and families. Escalating housing prices, concerns about climate change, and a growing sense of loneliness and isolation are pushing people to reconsider how and where they live.

The residences of Takoma Village Cohousing, located in Northwest Washington, D.C., flank a small common green that is open to the street. No fence separates the 43-home cohousing development from the single-family and commercial buildings that surround it.

“All of this was intentional,” longtime resident Alicia George says. “We wanted to be good neighbors.”

Being a good neighbor and living in community are essential values for people who choose cohousing projects like Takoma Village. In addition to the village green, the 1.4-acre (0.5 ha) development is anchored by a common house with a large communal kitchen and dining room, a children’s playroom, a cozy living room with a television and a bookcase full of puzzles, and a workshop. The 43 residential units range from one-bedroom apartments to four-bedroom townhouses. Completed in 2001, Takoma Village is the only cohousing project in D.C. In addition to other residences, it is adjacent to a juice bar, coffee shop, and community theater.

Cohousing is often defined as an “intentional community” with an emphasis on shared space, shared time, and shared values. Cohousing projects are usually the result of collaboration between a small group of people or founders working with developers, architects, and consultants to bring their vision to life.

Colorado developer and engineer Jim Leach built nearly two dozen cohousing projects across the U.S. West and Southwest before retiring a few years ago. For the past 15 years, he has lived in a senior cohousing project in Boulder, Colorado, which he developed as part of a larger master-planned community.

Leach points to the built-in cohort of buyers—who both provide financial equity and can speak up in support of projects during regulatory review—as a benefit of cohousing for developers.

“It’s a great way to make a contribution and a profit,” he says. Although arrangements vary, cohousing developers often earn a fee calculated as a percentage of total development costs or total development revenue.

In cohousing, individual residents and families own their own homes. Cohousing homes are typically smaller than the national average because communal spaces loom large. Although private space is essential, it is in common spaces where residents come together to learn, share, and build a sense of community.

A sense of community is also developed through shared decision-making and shared tasks. Weekly communal meals are a hallmark of cohousing. Responsibility for maintenance and other chores is distributed among residents, helping reduce total homeowners association (HOA) expenses and increase affordability.

Investments in energy efficiency also help bring down costs and enhance the sustainability of projects. Kathryn McCamant, an architect, developer, and cohousing pioneer who serves as an adviser to founding groups, says that developers working with founders can test the limits on sustainability.

“If you just want to maximize the investment, then cohousing is not for you,” McCamant says of developers. But for innovative ones interested in pushing the boundaries on design and sustainability, cohousing is a good proving ground.

“Because you have a buyers’ group who will give you real information about what they’re willing to pay for, like geothermal heating and cooling,” she says. Open budgets mean that developers and founders can discuss tradeoffs and priorities.

Cohousing holds out the promise of a more environmentally friendly, connected, and multigenerational way of living.

Aria Denver

In Denver, Colorado, developer Susan Powers built a 28-unit cohousing project inside a former convent building as part of the larger Aria Denver development, which will host 550 mixed-income residences, a production farm, and a small commercial strip when the larger development is complete.

Powers worked with a small group of founders to plan and design the cohousing at Aria, including the communal spaces—the kitchen, dining room, television room, business center, visitor suite, and bike storage.

Aria cohousing was born out of necessity: the campus’s convent building, originally erected for the Sisters of St. Francis, needed to be preserved, but it was not easily convertible to other uses. Together, Powers and the founders envisioned a new intergenerational, child-friendly community rooted in mutual inclusion and respect, connection, and ecological sustainability.

Going into construction, eight families put down nonrefundable 20 percent deposits, which served as an important source of equity for the project and enhanced its financial viability. The debt financing was provided by a standard commercial loan, Powers says.

Nine of the 28 homes in the cohousing development are permanently affordable, reserved for families making 80 percent of the area median income. This housing was built by transferring affordable housing requirements from a nearby development, for which Aria received $950,000. This funding was used to reduce the price of the affordable units by $100,000 each.

The total development cost for Aria Cohousing was $7.6 million in 2017; the developer fee was 5 percent of that, or $380,000. Construction costs totaled $5.1 million. Including the affordable units, the sales price was an average of $302 per square foot ($3,250 per sq m). The average per-unit sales price was $307,800.

Getting It Built

Across the United States, numerous founding groups are at various stages of work to get cohousing projects off the ground. One expert pegged the number of cohousing projects that are in the works at 120. Often, founding groups seek out architects and developers to help them find a site and navigate complex entitlements and financing requirements.

In other cases, such as at Aria, a developer has a site that they would like to use for cohousing and then they look for a founding group to work with.

In both cases, cohousing requires developers to be in co-creation mode. “It’s not for everyone,” says Powers, who notes that smaller developers are especially suited for doing cohousing.

For those who can make it work, the rewards can be great. “We were sold out before construction was completed,” Powers explains, adding that she learned a lot about buyer preferences working with the founding group.

Don Tucker, an architect and developer of the aforementioned Takoma Village project in D.C., agreed that a great benefit to developers is that there are certain buyers for the units who put money down, which reduces risks. “Construction lenders love that,” Tucker says. Also, rather than relying on information from focus groups, he was able to hear directly from the people who would live in the units.

“From a developer’s perspective, it is a way of knowing the market and taking the market risk out of the equation. That has appeal for both developers and lenders,” he says.

A coordinator consolidated feedback from the founding group for Tucker, who held the option to purchase the development site. “As long as we could accommodate the input and achieve financial feasibility, we’d do it,” he says.

For Tucker, having a site is key. “The site is the sorting hat,” he says. And getting access to land, especially in urban areas, can be a constraint for cohousing projects.

Still, architect and developer Charles Durrett, who with McCamant coined the term cohousing after observing models of it in Denmark, and has built 55 projects over the course of a multidecade career, says that entitlements have not been a problem. “Half of the projects that I have done are a rezone from single-family to multifamily, commercial to multifamily. I bring 100 people to the meetings—why would anyone tell them no?”

Durrett has built several cohousing projects as part of larger master-planned community developments, including Hearthstone in Denver. The co-housing buildings serve as the front gate and de facto welcome center for the communities, helping to bring energy and a sense of connection to the developments.

McCamant says that most cohousing is built with a budget that is similar to that of other new home developments. “Developers partnering with a cohousing group will typically limit their profit expectations,” she says, in return for the risk mitigation and financial contributions provided by the buying group. Cohousing buyers contribute predevelopment costs, provide equity, and help ensure that most houses are under contract before construction starts.

While every project is different, the developer’s guarantee fee is often 5 percent of sales, with additional compensation for development management services.

Diversity

Cohousing residents tend to be politically progressive and affluent—and they also skew white. “I definitely think cohousing has a diversity problem,” Powers says.

Takoma Village’s demographics do not represent those of Washington, D.C., as a whole, which until recently was majority Black. Resident Alicia George notes that the community is diverse in age, religion, sexual orientation, and other ways, but not in race, and increasingly not in income either. Addressing this gap across cohousing projects will require intentional strategies such as broader outreach and awareness building, and economic interventions like the inclusion of affordable housing.

At Aria Denver, the affordable housing component helped bolster the development’s economic and racial diversity. “This community is so much more interesting because of the mix of residents,” Powers says. “But it’s hard to figure out how to do that unless there’s a requirement.”

Sustainability

Environmental sustainability is a cherished ethos for the cohousing movement.

In Barcelona, Spain, the La Borda cohousing project by Lacol features a passive cooling and heating system. Cooperatively built by architect-residents, it does not have any parking for cars. Its 28 apartments have flexible walls—allowing for reconfiguration as residents’ needs change—and are organized around an open atrium.

In Cambridge, England, the Marmalade Lane cohousing project, which was built in 2018, includes 42 individual homes—including tidy brick rowhouses and apartments—clustered around a common house with a shared kitchen. The multigenerational project features a pedestrianized central courtyard, an outdoor play area and garden, and shared laundry, gym, and workshop. The development used environmentally friendly materials and designs that promote low energy use and a reduced carbon footprint.

Environmental efficiency is achieved across cohousing in multiple ways. Because individual cohousing units are smaller than average, they save building materials. At Takoma Village, energy for the common spaces is provided by rooftop solar panels, with the development generating enough power to sell it back to the grid. Power tools, ladders, and a lawnmower are owned in common and shared by all residents. A nook in the apartment building is stocked with clothing and supplies that owners no longer need—a popular community amenity. Parking is relegated to the outer areas of the development.

Governance and Sales

Many American cohousing projects, including Aria and Takoma Village, are established as condominiums and governed by a homeowners association.

Monthly HOA dues cover standard expenses such as taxes, insurance, and bookkeeping, as well as larger capital projects. The costs of day-to-day cleaning, gardening, and maintenance, which would otherwise need to be collected in HOA fees, can be reduced by cohousing residents taking on these tasks themselves.

Most cohousing units are sold directly by owners, bypassing real estate agents, with marketing and communications taken on by the cohousing development. At Takoma Village, a task force organizes regular tours and awareness-building activities for potential residents.

Being in Community

In an era of social disconnection and rising rates of loneliness, cohousing offers a powerful way of being in community.

Denver resident Trish Becker-Hafnor, who now leads the Cohousing Association of the United States, recalled coming home from a long day at work, sitting down in front of the television, and realizing she had never been inside her neighbors’ homes. She decided that there had to be a different way of living, and with her partner became an early resident at the Aria cohousing development.

For Becker-Hafnor, becoming a mother was an inflection point. “Having a child felt really intimidating,” she says. She and her partner dreamed of the mutual support that they had experienced in other chapters of their lives.

Alicia George credits the community at Takoma Village with making it possible for her to adopt her son. “Americans are geared to want independence. The reality is that we are social creatures,” she says. “This community has given me a sense that there are people who look out for me and my child.

“A lot of people worry about what they are going to lose” if they move to a cohousing project, George continues. “They don’t think as much about what they will gain.”

Older people can gain the ability to stay in their homes longer via cohousing. Some cohousing communities are built for people from specific age demographics, such as seniors, while others are intentionally multigenerational. But regardless of the model, cohousing’s systems of mutual support mean that many people can continue to live relatively independently as they age, reducing the need for paid nursing care and its public and private costs. And the evidence is clear that social connections help everyone live healthier, longer lives.

Getting to Scale

In Europe, in recognition of the social, economic, and environmental benefits of cohousing, governments have encouraged its development. Denmark is the global leader, with an estimated 7 percent of the population living in cooperative or cohousing communities.

The United States is far from that number. For cohousing to reach more people, Becker-Hafnor says that more developers will need to get into the cohousing business. Her organization, Cohousing Association of the United States, features some resources for developers, and McCamant runs a yearlong training program, 500 Communities, to teach professionals how to design and build cohousing and work with founding groups.

Portland, Oregon–based developer Urban Development Partners (UD+P) has completed multiple cohousing projects across the Pacific Northwest. Although there are barriers to getting cohousing projects built, including liability laws and financing, UD+P development manager Danny Milman says that “cohousing projects shouldn’t take any more time than any other residential development, if you’re pushing ahead the way you should be.”

UD+P has created a business line working with founding groups, who form a limited liability company, as a development consultant and guarantor of cohousing construction loans, in return for a project fee.

Milman says that the company’s commitment to building people-centered housing drives their work. “Of all the different types of buildings that I’ve developed or built, cohousing is the only one where it gets better over time. There’s nothing better than to build something that is going to be loved like that.”

In lots of ways, cohousing feels revolutionary. And almost miraculous. It must take a special kind of alchemy for a group of visionaries to look at a piece of land and imagine the community that could grow there.

But there also is something very traditional about cohousing. People have been living communally, in villages and in cities, for a very long time. Indeed, in many ways it is the modern American way of life—of every family in their own single-family home, expected to manage largely on their own—that is the historical outlier.

Becker-Hafnor describes cohousing as “a collection of homes built around common spaces where people eat together, make shared decisions, and share an ethos of living sustainably.”

This shared decision-making model requires developers to collaborate with buyers in ways that may feel unfamiliar. It may not be right for every developer. But even for developers and other land use professionals who may never be part of a cohousing project, cohousing offers both inspiration and a signal: a need and a market demand exist for a much broader range of housing typologies and ways of living than most places supply.

RACHEL MacCLEERY is co–executive director of the ULI Randall Lewis Center for Sustainability in Real Estate.

Learn more:

The Cohousing Association of the United States is a national nonprofit that advances cohousing.

The 500 Communities Program, run by cohousing pioneer Kathryn McCamant, is a year-long program for professionals interested in learning how to design and develop cohousing projects.

Cohousing Communities: Designing for High Functioning Neighborhoods, by architect Charles Durrett, describes how to design for social interaction and environmental sustainability.