Will downtowns in the United States rebound and prosper? This fundamental question still lingers more than three years after the global pandemic, after public mandates to work from home and following civil unrest and crime increases that began in many U.S. cities in 2020.

A report released by Philadelphia’s Center City District (CCD) in October 2023, Downtowns Rebound, tracks the recovery of twenty-six of the largest downtowns in the United States, exploring four key variables that impact recovery: the composition of downtown employment; the length of commute for workers; leadership exercised by business, civic and political actors; and perceptions of safety. While safety dominates headlines, the report finds, it may not be the most important variable.

How We Got Here: Since the 1980s, American city centers have responded to de-industrialization, suburbanization and disinvestment that had left many as declining 9-to-5 workplaces with few residents, diminished retail, and minimal nightlife. By 2019, nearly all major U.S. cities had downtowns that were thriving as mixed-use places for professional and financial services, information technology, education, research and health care, entertainment and culture, tourism, shopping, dining, and as preferred places to live.

Suddenly in 2020 and 2021, those old enough to remember experienced 1970s flashbacks as a barrage of news stories predicted “the death of downtowns” and a burgeoning, academic industry foretold a new, immiserating cycle of “urban doom loops” as lenders take back empty office buildings and municipal tax bases implode.

For decades, digital technology has untethered workers from fixed locations. But mandated shutdowns in early 2020 were unprecedented events. Widespread availability of web-based video-conferencing platforms for group meetings made transitioning to remote work almost seamless. Office occupancy, transit ridership, sidewalk vitality, and retail sales all dropped dramatically.

International tourism was suspended; domestic travel dropped precipitously. Arts and culture organizations shifted to virtual performances and exhibits. Evening vitality and restaurant table service evaporated, along with the sense of safety in numbers on sidewalks. Students left college campuses. Middle-class residents decamped from cities to second homes. In most U.S. cities there was a 70-80 percent drop between February and April 2020 in the volume of people present downtown.

Various metrics of recovery—employment, hotel occupancy, retail sales, housing prices and rents—indicate steady progress during the last three years. Still, most cities have not fully restored 2019 levels of vitality, leaving many offices empty. The duration of shutdowns enabled employees to grow comfortable with the convenience of remote and hybrid work.

Another robust discussion has emerged around the push-and-pull between employers and employees, between mandates or incentives, and between acquiescence or embrace of the virtual office. Employees point to reduced travel times and wardrobe costs and simplified daycare. Employers ask: can productivity, innovation, and mentoring be sustained with diminished human contact?

Secondary industries that depend on the presence of office workers—building engineers and janitors, transit workers, and lunch-hour restaurant workers—all have been adversely impacted. It remains an open question if downtowns will fully recover as centers of innovation and productivity for a broad range of workers at all educational and skill levels.

Downtown leaders now confront basic questions. Can recovery be accelerated to restore sidewalk vitality and tax revenues that support municipal services? With ridership below 60 percent of 2019 levels in Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, and San Francisco and barely over 60 percent in Boston, can major transit systems restore rider volume before federal relief funds expire?

Measuring Where We Are: CCD’s study focused on 26 of the largest downtowns, defined by job density. Using Placer.ai anonymized cell phone data for these dense nodes and surrounding half-mile residential rings, we compared rates of return in the second quarter of 2023 to the second quarter of 2019 for residents, workers, and visitors. Total recovery rates ranged from 69 percent in San Francisco to 100 percent in Nashville (Figure 1).

Focusing on the return of non-resident workers, using Placer.ai data and studies of the percent of downtown jobs that can be performed from home, we correlated worker recovery rates with downtown employer composition.

Four cities with the highest rates of worker return (Figure 2) have downtowns with strong concentrations of industries that depend on face-to-face experience: entertainment, hospitality, leisure and food services. It’s important to underscore too, that visitors constituted the largest share of people downtown in all 26 cities in 2019 and that their return requires a much lower commitment to place than signing an apartment or office lease or resuming the daily commute to work. The cities that lead in overall recovery—Nashville, San Jose, and San Diego—had both the highest share of daily visitors downtown and the greatest share of jobs in leisure and hospitality.

Three cities at the lower end, Denver, Portland, and San Francisco, excel in information technology, a sector comfortable with remote long before 2020 and with a current work-from-home average of 2.55 days per week. So, which is the chicken, and which is the egg? Are the widely reported quality of life and homeless encampment challenges in San Francisco and Portland, the cause of low worker return? Or was a void created by industries that most easily adopted remote work?

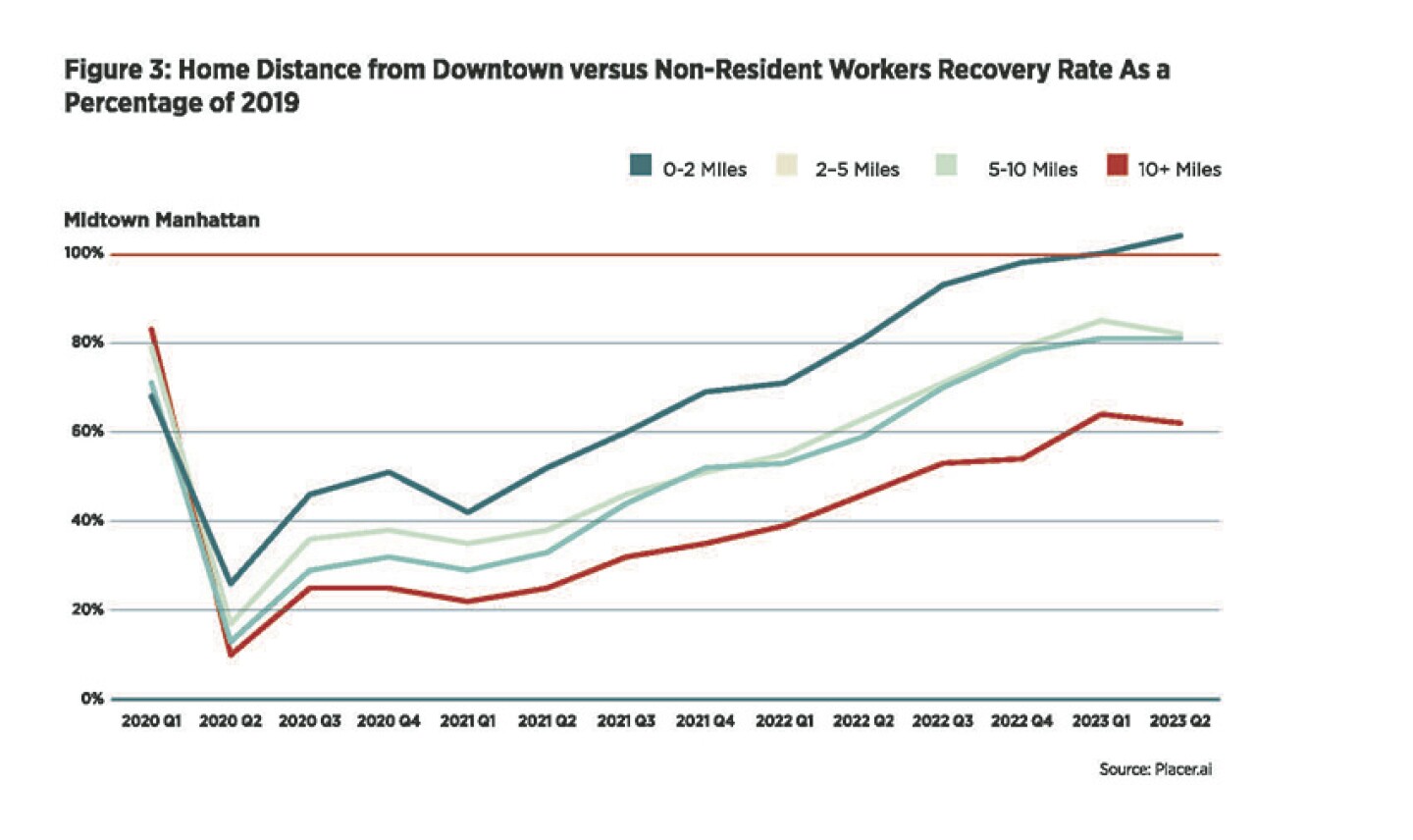

The Advantages of Live-Work Downtowns: Figure 2 shows Midtown Manhattan’s high rate of recovery, despite a concentration in financial and business services—sectors highly prone to remote work. But Figure 3, calculated from Placer.ai data, shows the return rate of those workers who live within 2 miles of their jobs at 100 percent; while those dwelling more than 10 miles away are only at 61 percent.

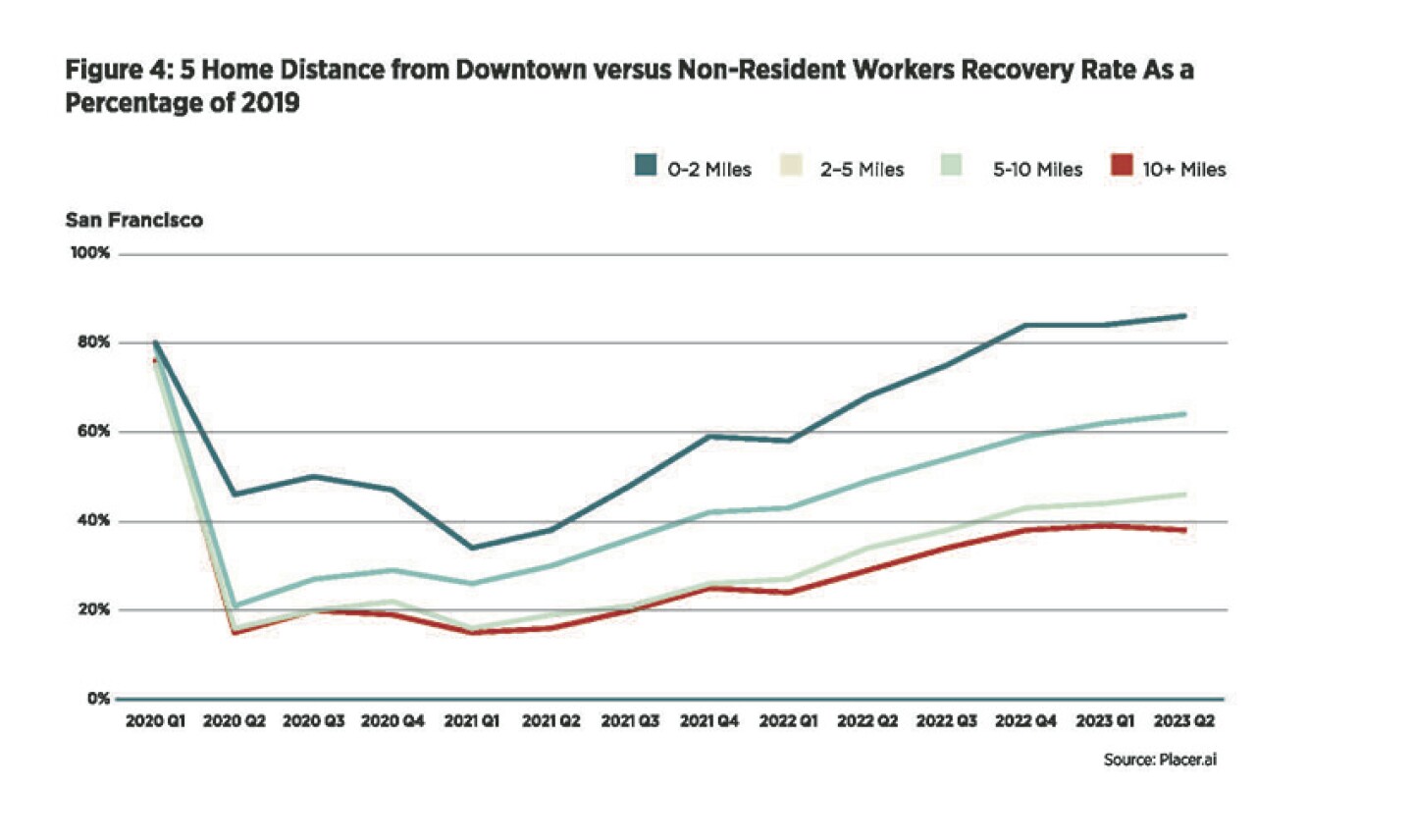

The same difference characterizes downtown San Francisco. Those who live within 2 miles have returned at a rate of 80 percent; those who live more than 10 miles away are below 40 percent.

This highlights the challenge for major urban transit agencies. They must do everything in their power to make the transit experience seamless and safe. But it also underscores the competitive advantage of those cities whose deliberate diversification strategies have transformed them from 9 to 5 office districts to live-work, walkable places.

Barrero, Bloom, and Davis also highlight the age of a city’s workforce as a significant variable in the intensity of work from home. “It is lowest among people in their early 20s and peaks among those in their 30s.” Young professionals in their twenties benefit most from professional networking, on-the-job training, and in-person mentoring. Those without children also socialize more at the workplace or in nearby establishments after work. “They are more likely to live in small or shared apartments, which reduces the appeal of working from home. People in their 30s and early 40s are more likely to live with children and face long commutes, raising the appeal of work from home.” Those downtowns with condominiums for empty nesters get the same proximity advantages for older workers.

Residents, however, remain the smallest share of those downtown each day in the twenty-six largest cities. In Philadelphia, with one of the largest downtown populations among the 26, Center City residents constituted just 13 percent of those downtown in January 2019; workers accounted for 34 percent; visitors —tourists, convention attendees, shoppers and diners and those coming to access services—made up 53 percent.

Still, from 2011 to 2019, employed residents living in core downtowns grew more rapidly than overall employment in many cities. Philadelphia, San Francisco, Seattle, Washington, Boston, Denver, Midtown Manhattan, and Portland all have more than 20 percent of their downtown workforce living within two miles of the core. Many of these cities also have more than 40 percent of greater downtown residents who work in their greater downtowns, reducing the length of commute.

The Placer.ai data also confirms that downtown residential populations were impacted only temporarily by the pandemic. Following a net outmigration in 2020, nearly all 26 downtowns have larger populations today than in 2019.

Leadership Matters: Command and control no longer works. The Gensler design firm talks about making the office a destination, not an obligation: a place for interaction, enriched by programming. Those who listen closely to the concerns of their workers and focus on the collaborative, socializing, and mentoring activities that can only occur in person, have achieved greater levels of employee engagement, return, and higher rates of productivity. They also restore jobs and opportunities for workers in other industries, at all skill levels, who depend on their presence downtown.

Comcast is an excellent example. By type—information technology and communications—they should tend toward remote. But they have steadily moved to four days a week in their corporate headquarters in Center City Philadelphia. It may be easier for firms like this, with their own event and marketing teams, to direct these resources internally. Others may benefit from outside assistance.

Some human resources professionals suggest that while perks and parties may help, more access to company leadership could increase employee satisfaction, as might enhanced commuter benefits and compensation for more days at the workplace. Others cite the inherent benefits of face-to-face interaction for innovation and on-the-job learning, as well as the spur to productivity that comes from chance encounters with competitors on downtown streets. A good CEO also inspires employees to buy into a larger vision.

Safety Matters: Public leadership remains paramount. The killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and others commemorated in Black Lives Matter protests prompted civil unrest in some cities, vandalism and looting in others. This stimulated a profoundly needed debate about the appropriate role of police and optimal ways to produce public safety.

But it also generated demands to defund police that were implemented in several places, while inducing lower staffing levels in others, as many officers chose to leave the profession or move to less contested communities. This impacted both the perception and reality of public safety. Recent memories of civil disruption, boarded-up businesses, and diminished foot traffic that made the presence of the mentally ill and addicted appear more prominent—all combined to foster anxiety about safety downtown. But apart from a spike in retail theft, nearly all the factors that create unease in most downtowns today relate to quality-of-life challenges and homelessness.

In 2018, Patrick Sharkey’s Uneasy Peace urged a renewed commitment to community policing, shifting the role and image of police officer from warrior to guardian so that departments become more engaged in, and trusted by, the communities they serve. One can reject racist and illegal police actions and over-reliance on jails, yet still affirm an appropriate role for well-trained police working in concert with other mental health, addiction, and homeless service providers in addressing challenges that go beyond simple law enforcement. It should be an essential part of the recovery strategy for every city.

Whether in public safety, workplace practices, or by diversifying downtown land use, the last three years are a profound reminder that successful cities will be those that respond best to challenges and reshape themselves for new realities.