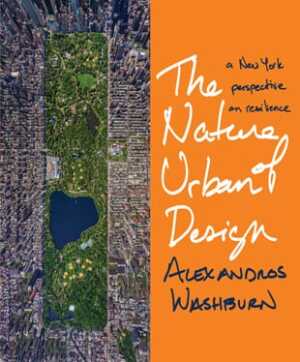

The Nature of Urban Design: A New York Perspective on Resilience

Alexandros Washburn

Island Press

2000 M Street NW, Suite 650, Washington, DC 20036; www.islandpress.org.

2015. 264 pages. Paperback, $30.

In his book The Nature of Urban Design, Alexandros Washburn writes that “nothing important in a city can change without an alignment of politics, finance, and design.” As New York City’s chief urban designer under Mayor Michael Bloomberg, he played a key role in the planning and building of the High Line, the 21st century’s most notable civic design project. That experience shaped his view of city design.

For Washburn, politics, both top down and bottom up, is the “greatest force in determining what gets built,” while a successful financial model is the “transformational trigger that allows repetition of the elements to form the eventual urban design pattern.” Urban design does not make cities, but “makes the tools”—the rules, plans, and projects—that guide a city’s transformation.

Urban designers do not sit down at the drawing board to lay out cities. Instead, they collaborate with residents, developers, and politicians to create design rules and policies that guide future growth proposals. The bulk of that growth will be repetitive, building over and over by right under existing codes. Only rarely, when consensus is reached to change the rules of the game, will design be transformational.

The High Line is such a transformational design, forever changing lower Manhattan’s West Side. Washburn tells the inside story (much of which is no doubt familiar to Urban Land readers) of how this happened, starting from the first effort in 1999 by two citizen activists to protect the rusting and abandoned elevated freight railroad from demolition. They formed a nonprofit organization, Friends of the Highline, and developed their political connections, financial structure, and design ideas.

The adjacent West Chelsea neighborhood had declined after the meat packing industry moved out in the 1980s. Speculators bought land under the rail line and rented it for parking. Meanwhile artists and galleries arrived. Seeing the opportunity to build five-story buildings on their parcels, the landowners petitioned the city to remove the rail structure. They convinced then mayor Rudolph Giuliani, who signed the demolition order as his term ended.

But the demolition order was rescinded by new mayor Bloomberg, who appointed a Friend of the High Line, Amanda Burden, to chair the city’s Planning Commission (Burden would later be honored by ULI with the 2009 J.C. Nichols Prize). Now the question was how to renovate the structure, satisfy the landowners and neighborhood, and pay for it all. Burden called for a strategy that linked High Line renewal with neighborhood renewal and that let the landowners realize their land value so they would drop their demolition demands.

Working with the stakeholders, the city’s urban designers created an innovative new zoning district, the Special West Chelsea District, with the goals of transforming the High Line into a unique linear park, providing new housing, preserving the art galleries, adding new uses to the neighborhood, and maintaining light and air around the new park. A transfer of development rights provision allowed landowners to sell their rights to receiving sites on the area perimeter. Buyers of the rights were given a 30 percent rights bonus if they developed 20 percent of their new building as affordable housing.

Washburn believes that every great city must be able to carry out big visions while attending to the fine-grain quality of street life and providing daily access to green spaces. He judges urban design in terms of how well it meets the standards of three “bosses”—the grand scale of Robert Moses, the neighborhood quality of Jane Jacobs, and the natural green space of Frederick Law Olmsted. All three would find the High Line meets his or her standards.

Moses would be impressed with the $2 billion in private investment, 12,000 new jobs, and transfer of 35,000 air rights since the rezoning. Jacobs would appreciate the district’s bustling cafés and galleries, active street life, and mix of old and new buildings. And Olmsted would be amazed at the new linear park, 20 feet (6 m) in the air, attracting more than 4 million visitors a year as the city’s most visited park per acre.

Washburn’s High Line story convincingly supports his collaborative urban design approach. His other big urban design story concerns ensuring the city’s resilience in the face of future disasters. Washburn experienced Hurricane Sandy as a resident of Brooklyn’s Red Hook neighborhood and is aware of climate change perils, but he is less convincing in evaluating design for averting potential catastrophes.

We already know that urban design can mitigate climate change by slowing the rise in greenhouse gas emissions through increased walkability and transit use, building energy efficiency, use of renewable energy resources, and carbon capture. We also already know that urban design can adapt to existing climate change risks by increasing structural fortification and social resilience, and facilitating planned retreat. But we do not know how these various actions interact with each other.

Washburn would track and measure the effectiveness of mitigation and adaptation through a system of risk “ecometrics.” His system would account for mitigation impacts on reducing the probability of climate change risks together with the impacts of adaptation on reducing the consequences of future disasters. In theory, this is an impressive system of risk metrics; in practice, it is light years away from being operational.

As befits a book by a wise urban designer, The Nature of Urban Design brings together both the practical and the visionary. It correctly notes that cities are mostly built up by repetitions of tried and true approaches. However, it also teaches us that, in rare cases, wonderful transformations can occur under the right mix of politics, finance, and design.

This book was first published in 2013, but is now available in paperback.

David R. Godschalk is planning professor emeritus at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and coauthor of Sustaining Places: Best Practices for Comprehensive Plans (APA Planning Advisory Service, 2015).