In response to increased awareness of nature and the market demand for more and higher-quality connections to it, our approach as designers and architects continues to evolve beyond simply blurring the line between indoor and outdoor spaces. Providing end users with a choice that originates from a binary view—either indoor or outdoor—is no longer enough.

It is often our aim to erase the line between inside and out and understand how we can provide spaces across a spectrum of what I call outdoorness. Designs born out of this concept are aimed at providing end-users with a full range of spaces that offer an optimal level of comfort according to the weather, time of day, and type of use, all tied to a greater connection to the outdoors.

Concept as a Continuum

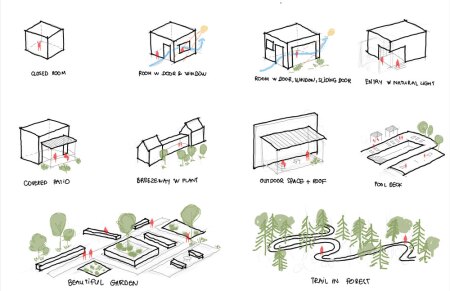

Outdoorness may not seem like a term easily applied to the built environment, but if you picture the concept as a continuum, much of our environment already incorporates some aspects of the concept. There are different gradients of outdoorness, and how that affects quality and sense of place roots a project in its context.

Think of it as a y-axis: at the left would be the interior-most room in a building, typically with a gradient of 0 outdoorness, and as one moves toward the exterior walls, the gradient increases. For example, a bedroom with operable windows with a view of the outside would be on the left end of the continuum, around a level 1 or 2. Covered spaces with three walls of windows would be representative of an even higher gradient. At the end of the scale, the highest level of outdoorness could represent a person on a trail in the Great Smoky Mountains, where there are no buildings and no cars.

Practically speaking, outdoorness can take many forms. For example, in interior lobby spaces, we boost outdoorness by bringing in more plants, sunlight, and fresh air. We design indoor amenity spaces with more operable windows. With exteriors, we often increase the indoorness by focusing on microclimates and creating outdoor rooms. This can be done by extending shade structures from the building, using breezeways as active and passive space, and employing pavement and plants to define a room’s “walls” and “floors.”

City Club Apartments (CCA) Detroit in Michigan has an active feel, like that of an old European town square or market, with the spaces offering a moment of reprieve from the area’s busy surroundings. The outdoorness of CCA Detroit is a little less overall than that of Waterford Bay—5 or 5.5 on the continuum. (BKV Group)

Biophilic Benefits Abound

Though it has been conventional wisdom that much more opportunity exists to incorporate greater outdoorness in projects in warmer climates such as Florida, this is no longer the case. Even in colder climates like Minnesota, designers have been opting for context-responsive buildings that engage with the neighborhood and adjacent uses through activated outdoor spaces.

From a biophilic standpoint, great outdoor spaces may have more human value than highly amenitized indoor spaces. Through decades of research, we have come to realize that access to the outdoors and connectedness to the environment are important parts of human nature when it comes to physical health and mental well-being. In many ways, spaces incorporating outdoorness offer an escape from daily pressures and a much-needed break from technology. Research has shown that among other benefits, exposure to natural environments can lower a person’s blood pressure, reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, and boost the immune system.

Landscape architects have been willing into place this shift to prioritizing outdoor space and exterior amenities as a critical component of human health, but it took the COVID-19 pandemic to accelerate it and create what I believe is a perpetual change. An example is the number of people who decided to stay and live in the mountains of Colorado rather go back to the office once COVID restrictions ended. For them, the change is a permanent thing.

Authenticity

My colleagues at BKV Group and I recently visited a potential site for a new project in downtown Kansas City, Missouri—a dilapidated 1930s warehouse building. Half the roof had caved in, the windows wereall busted out, and vines were creeping in—yet the space looked and felt great.

All of us on the tour asked, “Why is this such a fantastic space?” What we realized is that the building no longer dominated the landscape. The disintegration of the built space created a better balance and connection to nature. Options existed for us to either be in the shade or the sun, the surrounding views were open and inviting, and there was a general human scale and highly textural quality to the space. It was a space that was hard to define as either outdoor or indoor. I now think about that dilapidated building and aim for a blurred level of outdoorness in all projects.

This all supports a larger vision for how my firm and others are focused on a holistic approach to connecting with nature for a design ethos of authenticity. We champion projects that reflect and celebrate the culture and ecology of their setting. This is a recent divergence in our profession and practice that historically (and sometimes currently) has led to buildings that dominate the landscape and context. Unless designers consider an authentic, contextually responsive project, buildings can become monoliths that have a long-term negative influence on their surroundings. Authenticity is paramount when designers consider projects affecting places that have a large impact on people for decades to come.

Located in a serene setting adjacent to the Mississippi River, Waterford Bay is a four-story, 243-unit rental community on a 295,000-square-foot (27,400 sq m) property deeply integrated into its natural surroundings in St. Paul, Minnesota. The outdoorness of Waterford Bay as a whole would earn about a 6.5 on the continuum. (Courtesy of BKV Group)

Beyond the Limits of Geography

Among the sectors of the built environment, hospitality has been a trendsetter in embracing outdoorness, especially luxury hotel properties, which often incorporate open lobbies that connect to outdoor pool and recreation areas or the beachfront. These concepts have become extremely popular in newer multifamily buildings as well. Whether urban or rural, high levels of outdoorness can be incorporated into new construction regardless of geography,

Located in a serene setting adjacent to the Mississippi River, Waterford Bay is a four-story, 243-unit rental community on a 295,000-square-foot (27,400 sq m) property deeply integrated into its natural surroundings. From the building’s floor-to-ceiling glass windows and outdoor patios offering sprawling views of the Mississippi to the native on-site prairie grasses and stormwater management system that drains directly into the river, essentially every aspect of the design was tied to nature.

From a biophilic standpoint, the property’s south end has a large amount of sun exposure, and natural vegetation surrounds all sides of the building. Outdoor communal areas—divided by plants that bring in a variety of greens and other colors as a functional element—help break up the spaces into areas that allow small groups to congregate. In many ways, being on the property is equivalent to sitting under a big oak tree. On an outdoorness scale, Waterford Bay as a whole would earn about a 6.5.

In contrast, the seven story, 228-unit CCA Detroit is situated in an urban location in the heart of downtown Detroit overlooking Grand Circus Park. It has an active feel throughout its indoor and outdoor spaces that aligns with the surrounding neighborhood. It has countless details inspired by nature, including curved lines that mimic movement as well as the patterns and shapes of the exterior courtyard, which has a triangular shape that makes it feel larger than it actually is. This sense of movement makes the courtyard feel like a new space every time one steps into it.

The green space was designed to accommodate maturation, allowing the trees to fill out to create a natural canopy. CCA Detroit also incorporates garage doors in the first-floor lobby area leading to the exterior courtyard that bring in abundant natural light. While the property has an active feel, like that of an old European town square or market, the spaces themselves offer a moment of reprieve from the area’s busy surroundings. The outdoorness of CCA Detroit is a little less overall than that of Waterford Bay—5 or 5.5 on the continuum.

Industrywide, many components of outdoorness are branching out beyond multifamily housing to other sectors like city and suburban offices, government facilities, and libraries. As an understanding of the importance of indoor/outdoor connectivity continues to accelerate across the built environment, it will be interesting to see how high the bar gets set. One thing is certain: the sky is the limit.

COLLIN KOONCE is an urban design and landscape architecture leader, and partner at Minneapolis-based BKV Group, a holistic design firm.