Placemaking—combining elements of the built environment in a compelling way that attracts people—is the essence of real estate development. Creative placemaking takes that concept further, with the placemaking effort led by arts and cultural considerations that help shape not only the physical character of a place, but also its social character. As Anne Markusen and Ann Gadwa Nicodemus wrote in “Creative Placemaking,” a 2010 paper for the National Endowment for the Arts, “Creative placemaking animates public and private spaces, rejuvenates structures and streetscapes, improves local business viability and public safety, and brings diverse people together to celebrate, inspire, and be inspired.”

Creative placemaking, done well, can deliver high value to its stakeholders, including the community, developers, and public and private partners.

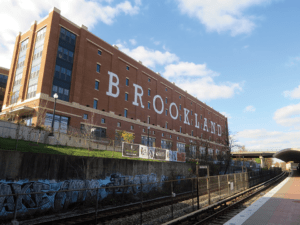

The distinguishing features of creative placemaking and the attributes present in a well-executed project are evident in three very different real estate developments: a transit-oriented, mixed-use development project in the once-quiet community of Brookland in Washington, D.C.; the redevelopment of a blighted building in the changing Tenderloin community in San Francisco; and a neighborhood revitalization effort in Mill Hill in Macon, Georgia.

Monroe Street Market, Washington, D.C.

Monroe Street Market transformed Catholic University of America’s South Campus and the surrounding Brookland neighborhood in the northeast quadrant of Washington. Monroe Street Market comprises a sprawling five-block complex, just three miles (5 km) from the U.S. Capitol and adjacent to a Metrorail station and bus lines.

This vibrant mixed-use community includes 720 multifamily residences, 45 townhouses, and 83,000 square feet (7,700 sq m) of retail space. An important component of the development is the inclusion of 27 affordable artists’ studios totaling 15,000 square feet (1,400 sq m) on the ground floor of two of its three residential buildings. The Art Walk between the buildings features a 1,000-square-foot (93 sq m) public square with a fountain and a 70-foot-tall (21 m) clock tower at one end, and a 3,000-square-foot (280 sq m) community arts center at the other, both serving as focal points for the complex where special events are held and residents can gather.

Abdo Development, based in Washington, D.C., and the Bozzuto Group, based in Greenbelt, Maryland, assembled a diverse team of partners to implement their plans. The project has been under construction since 2011, artist occupancy began in 2013, and the last phase of the project is scheduled to be completed in 2017.

Catholic University owns the site, which provides an entrance point to its South Campus; CulturalDC, a nonprofit organization that provides creative placemaking services primarily to real estate developers and property owners, helped design and activate the artists’ studios; and Dance Place, a nonprofit dance company that has been anchored in the community for decades, provides ongoing dance programs in the development’s Edgewood Community Arts Center and the Art Walk and plaza. Programming includes Third Thursday open artists’ studios, Saturday farmers markets, free weekend dance performances, and free public fitness classes at the Edgewood center on Saturdays.

The Monroe Street Market design team improved walkability, traffic patterns, and pedestrian crossings along Michigan Avenue and Monroe Street, making the area more pedestrian friendly. Residential amenities include a health club, swimming pool, and yoga center, plus easy access to the nearby Metropolitan Branch bike trail.

The development has expanded the availability of local retail options, enabling more money to stay in the community. The art features attract visitors and tourists, who also contribute to the local economy. As a central gathering place, Monroe Street Market has helped unify the Brookland community. This year, ULI Washington recognized the project with an Award for Excellence in Mixed-Use Development.

The Hall, San Francisco

The Hall is the temporary activation of a warehouse building that had been blighted and vacant for seven years before Developers/Partners Tidewater Capital, a San Francisco–based investment and development firm, and War Horse, a Baltimore-based development firm, purchased the property in 2013.

The building is located in the Tenderloin, a San Francisco neighborhood that has long faced many social challenges such as drugs, unemployment, crime, and poverty.

The Hall, an experiment being conducted in 4,000 square feet (372 sq m) of temporary retail space, is focused on community engagement and urban revitalization while the development team seeks entitlements to redevelop the site to provide 186 units of rental housing above 10,000 square feet (929 sq m) of retail space. The future development is planned to include a mix of market-rate and affordable housing and is expected to break ground next year.

The interim use consists of six food stalls placed in a food-hall setting and run by local entrepreneurs—all former food-truck vendors. There also is a bar, plus events programming aimed at promoting positive change in the community.

The Hall is more than a culinary arts initiative. The space serves as a gathering place—a clubhouse of sorts. It was built with the intention of fostering connection among members of the community by creating a space to convene, break bread, and share experiences. Since opening in October 2014, the Hall has served more than 4,000 meals a week, been the site of more than 90 community events, and donated more than $35,000 to local nonprofit groups.

Last year, it began serving monthly community breakfasts, open to all, during which the development team provides updates on the broader project, seeking input from stakeholders while also discussing such community topics as public safety, small business development, housing affordability, and arts in the community. Further, in an effort to address neighborhood unemployment, the Hall organized and sponsored two job fairs to help match employers with neighborhood job seekers. The Hall is a finalist for ULI’s 2016 Global Awards for Excellence.

Mill Hill East Macon Arts Village, Macon, Georgia

Mill Hill is located in the Fort Hawkins neighborhood, known as the birthplace of Macon. Once a village for people working at a local cotton mill, the neighborhood is composed of properties that are now 46 percent vacant and blighted, according to a study by the Macon-Bibb County Urban Development Authority (UDA).

Although the area is now disconnected from the economic drivers around it—residents are not employed at the local hospital or nearby tourist attractions—the strategic plan for Macon’s urban core lays out hope that the new community arts center and artist housing being developed there will help transform the area into an economically and culturally thriving community.

The new Gateway Park, being developed by the Macon Arts Alliance, Macon-Bibb County UDA, and other partners, will connect the community to nearby tourism assets, such as the Macon Centreplex, the Marriott Macon City Center, and the Ocmulgee National Monument, which honors 17,000 years of documented human habitation in the area. The Ocmulgee mounds were built 1,000 years ago by Native Americans during the Mississippian Period and are on the former land of the Muscogee Nation.

Vacant mill houses will be transformed into affordable artist live/work housing—seven units in the first phase, each providing 900 square feet (84 sq m) of space for one occupant—helping reduce blight and becoming a hub for economic activity.

The Bibb Mill Auditorium, built in 1920 and now being renovated, will be reborn as the Mill Hill Community Arts Center. The future arts center received a new roof this year, paid for with an anonymous $211,000 gift. With the building stabilized, restoration continues through an $813,000 investment by the Macon-Bibb County government.

During planning, the project was supported by the White House’s Strong Cities, Strong Communities Initiative and an Our Town grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). The steering committee includes prominent organizations, such as the Regency Hospital Company, the Macon Coliseum Hospital System, the Macon Arts Alliance, and the Knight Foundation, as well as the mayor of Macon-Bibb County.

The project team worked with the community to identify its unique assets. It discovered that many residents like to cook, so a culinary school is part of the redevelopment plan. The goal is to attract new residents and businesses to the area, helping the local economy grow while affordable homes are retained for those who have long resided there and helped create this distinctive place.

Four Essential Tasks

In research for their paper on creative placemaking, Markusen and Nicodemus, spent six months surveying successful projects, identifying ingredients of success as well as common challenges. Their case studies cover many types of communities, from older industrial inner cities to younger, lower-density cities, and from rural towns to Native American reservations. This work and their later reflections highlight four essential tasks for those seeking to carry out successful creative placemaking projects.

- Build cross-sector partnerships. The Monroe Street Market’s public, private, and community partners—including Abdo Development, the Bozzuto Group, Catholic University, CulturalDC, Dance Place, artists, and others—were vital contributors to the drive to unify the community and promote its economy through the arts. Similarly, the Mill Hill East Macon Arts Village has a team of many players at the local and national levels who have helped the project build momentum.

- Mine community assets and honor the uniqueness of place. The Hall creates a physical sense of place in what was once a vacant building, serving as a gathering space in the geographic middle of different communities, providing a place for fostering and strengthening relationships within a challenged neighborhood. The Mill Hill East Macon Arts Village promises to be a shining reminder of the birthplace of its city, Macon, while bolstering its residents and the local economy. Both teams worked with assets already present in the community.

- Explore creative financing. Money can come from unforeseen places, such as the $211,000 gift to replace the roof on the Bibb Mill Auditorium. Stakeholders can use leverage or find partners to help share the cost of the project, as was done when Macon-Bibb County contributed $813,000 to complete construction of the auditorium and NEA’s Our Town grant provided seed funding.

- Seek equity and inclusiveness in project implementation. Some thought leaders acknowledge that creative placemaking, though intended to be an equalizer among people, has at times had the reverse effect, leading to the displacement of residents as investments boost the local economy and make areas unaffordable for some people. Mill Hill, for example, is starting with a goal of achieving equity and inclusiveness, a strategy likely to cultivate community pride and uplift not only in the local community, but also in Macon at large. The Hall employs innovative community engagement through its weekly breakfasts and sponsored job fairs, which directly address neighborhood unemployment, as well as, indirectly, related issues, including crime and drug use.

Benefits of Placemaking

Through creative placemaking, communities have the opportunity to become healthier places to live and work. Research has shown a strong connection between art and cultural assets in a community and social outcomes, including improvements in health, social connections, safety, housing burden, and economic well-being. Local governments also receive benefits such as increased tax revenues, job growth, and reduced public safety risks.

In addition, there are benefits for real estate development professionals—developers, architects, planners, and others—who take measured risks and create groundbreaking projects, as J.C. Nichols did in Kansas City, Missouri, with his Country Club Plaza (est. 1922) and Abdo and Bozzuto did in the nation’s capital nearly 90 years later with their Monroe Street Market.

A recent focus group with developers, architects, planners, artists, and nonprofit arts organizations, convened by ULI Washington, highlighted potential benefits of creative placemaking for real estate developers. They include:

- Lower development costs. “Time is money,” said one focus group participant. Community engagement and buy-in, often critical to project success, can be costly to obtain. Gaining early community buy-in and support hastens zoning approvals and progress on other aspects of the development cycle. The focus group recommended early engagement of artists and other members of the creative class for help in creating a sense of place showcasing existing community assets.

- Higher project value. Uniqueness of place helps establish premium value for a project. For example, “expect to gain 5 percent additional rent when you put a grocery store on the ground floor of a new residential building,” one focus group participant said. Similarly, Monroe Street Market’s unique Art Walk, artists’ studios, and other factors, including innovative mixed-use project design, elevated the value of the residential units in the complex, helping investors realize a higher return.

- Enhanced branding and market recognition. Just as Nichols received national and international recognition for Country Club Plaza—greatly enhancing his brand beyond Kansas City and Missouri—innovative art, culture, and design features can open doors and create opportunities that far exceed the outcomes of budgeted marketing activities.

High potential value can be realized from placemaking led by innovative art, culture, and design, and implemented effectively and employing lessons learned and best practices. The community, government, developers, and other public and private partners all stand to benefit. While creative placemaking can be applied to projects large and small and across multiple land uses and real estate disciplines—housing, mixed use, transportation, and infrastructure—possibly the greatest opportunities can be found in communities in need of revitalization.

A focus of ULI over the next two years, funded by a $250,000 grant from the Kresge Foundation, is to raise awareness of creative placemaking as an important component of building healthy places and to provide tools to assist in implementation of creative placemaking in real estate development projects.

ULI’s vision is that over time, increased use of creative placemaking will improve living conditions for low-income and other vulnerable populations living along commercial corridors and in neglected communities. The Institute’s work is intended to be scalable and should be useful regardless of project size or income level in target communities.

Juanita Hardy is ULI senior visiting fellow for creative placemaking.