Amid the ongoing conversation about the post-pandemic future of North America’s largest downtowns, many observers draw a straight line between the drastic reduction in full-time office workers and the elevated retail vacancy along high-profile downtown shopping streets. Consider this December 2023 quote from the Wall Street Journal: “Millions of employees are no longer commuting every day, leaving many offices half-filled and retail stores struggling for customers.”

The impact of daytime workers on this sort of retail has long been overstated, though. Yes, they provide critical support for lunch eateries and coffee bars, as well as select services including fitness studios and shoe repair. But downtowns could never count on this demographic for much more than that.

Consider the rule of thumb that employees typically do not venture more than nine minutes away from their workplace. In most large downtowns, the primary sub-district for office towers has no meaningful cluster of fashion retailers within such proximity.

The reality is that consumers typically make such purchases closer to home or during vacation. Indeed, the few downtowns that have established and retained critical mass in these categories over the years were able to do so largely as a result of leisure visitors and city residents.

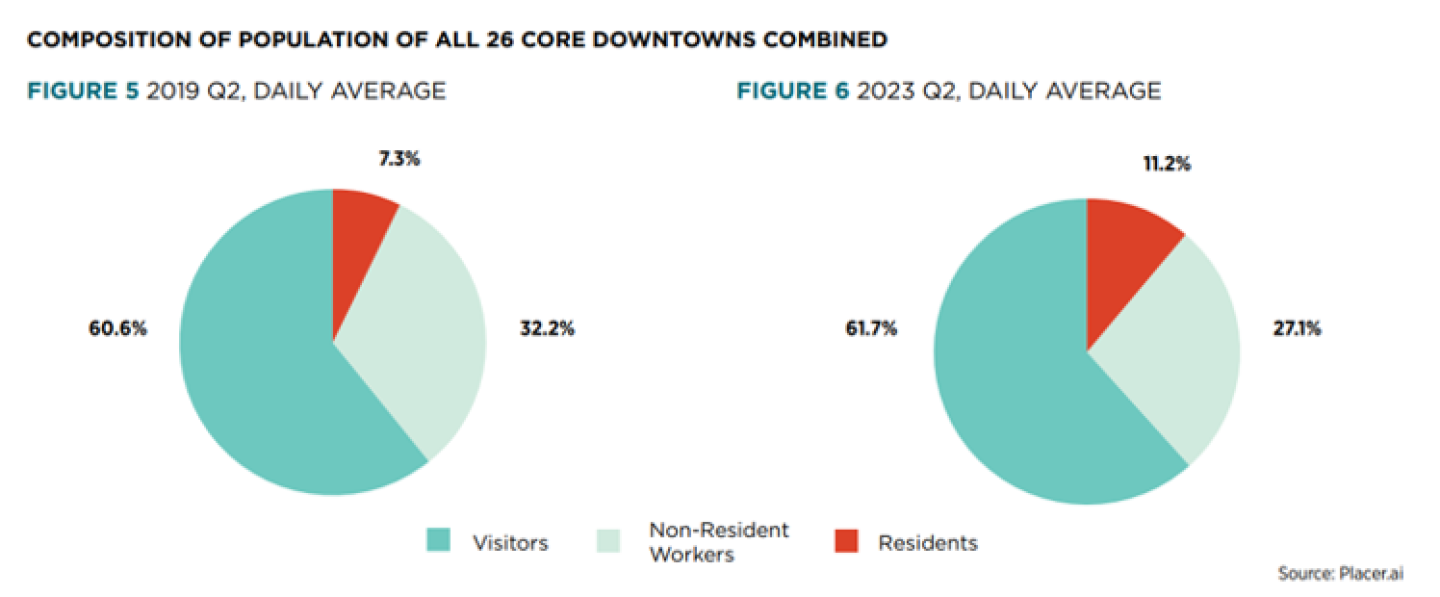

According to the Downtowns Rebound: The Path to Data-Driven Recovery report released by Philadelphia’s Center City District in 2023, visitors and residents accounted for nearly 73 percent of post-pandemic foot traffic in the nation’s 26 largest downtowns in Q2 2023 —having increased from roughly 68 percent just four years earlier—as well as the bulk of higher-priced discretionary purchases there. Note that “visitors” in this case includes anyone who does not live or work within the designated geography, like, for instance, residents from other neighborhoods or suburbs.

(Philadelphia Center City District)

So, although remote/hybrid work can rightly be held accountable for the ground-floor struggles in such mono-dimensional office enclaves as Chicago’s LaSalle Street and San Francisco’s Financial District, it does not deserve blame for the depressed foot traffic in true shopping destinations such as Magnificent Mile or Union Square.

Indeed, places in the latter category have been contending with a more complex set of challenges.

What’s really behind the elevated retail vacancy?

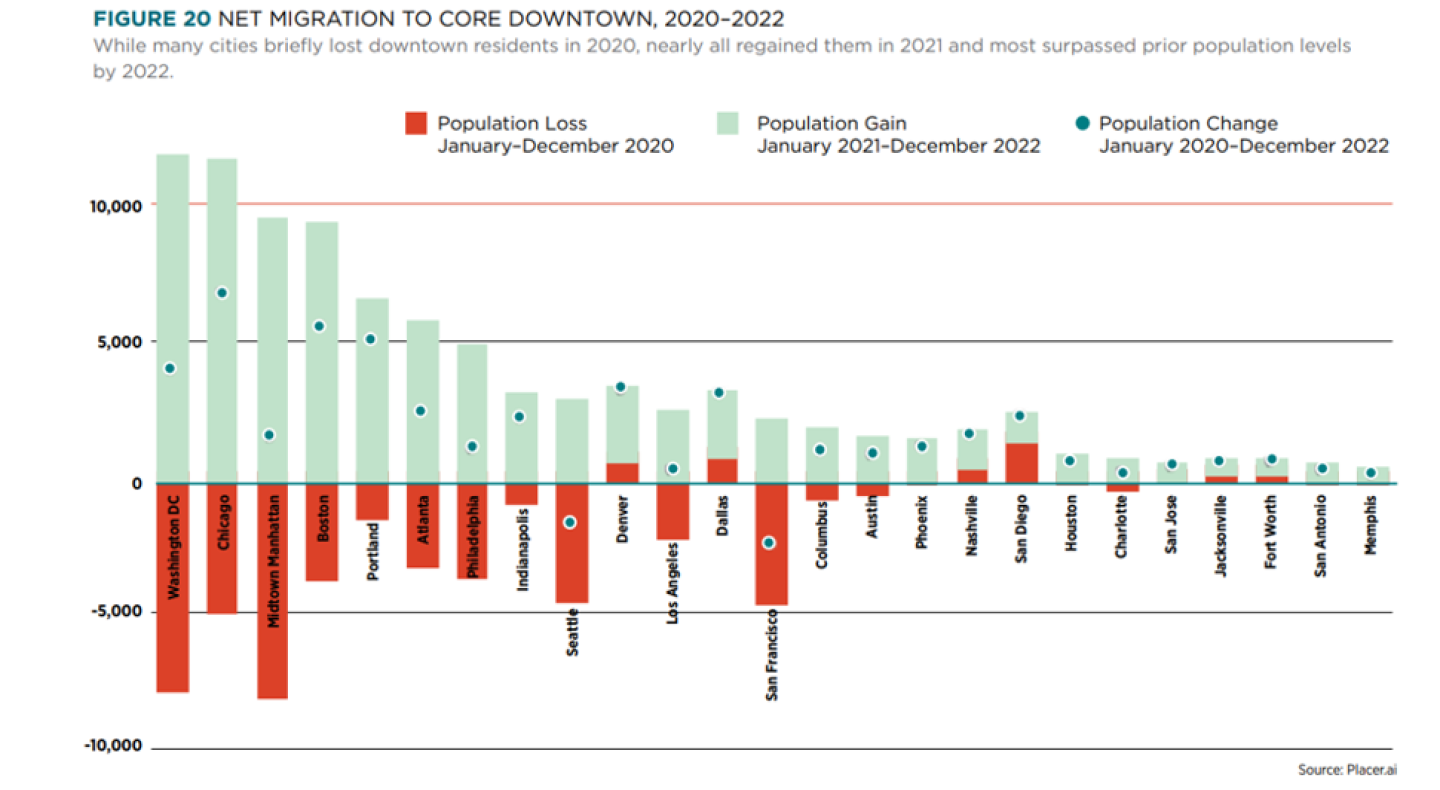

One such challenge, a severe contraction in consumer demand, stemmed from sources other than office workers in the pandemic’s first few years—specifically, free-spending foreign tourists, who effectively disappeared, and affluent urban dwellers, many of whom fled the cities in the name of social distancing, millennial life-stage transition, or both. Both of these trends went into reverse by 2022.

According to the aforementioned Downtowns Rebound report released by Philadelphia’s Center City District in 2023, while many of the nation’s 26 largest downtowns lost population in the pandemic’s first year, all of them experienced net gains from 2021 to 2022 and all but two had exceeded pre-pandemic levels by the end of that period.

The more visible presence of people suffering from mental illness, drug addiction, and being unsheltered; perceptions of widespread retail theft; and an unsettling sense of pervasive disorder have received much attention and, no doubt, played a role in deterring would-be shoppers, as well as prospective tenants. These elements have ossified at this point into an established narrative that seems impervious to new data, though untangling the extent to which these variables are more cause or effect is not easy.

Arguably, however, the most impactful trend—and the one least discussed—involves tenant demand, specifically shifts since the mid-2010s in the retail brands that are popular and the kinds of floorplates that they favor. Unlike the other challenges, this one predates the pandemic and might endure well beyond it.

In the early 2000s, major retailers started opening multiple flagship stores on high-profile urban shopping streets around the world. These massive, multistory showcases were intended primarily as marketing vehicles where consumers could “experience the brand,” thus creating a halo effect that would drive sales on digital channels, in branch locations, or through wholesale partners.

Alas, such flagships, situated along some of the highest-rent corridors on Earth and requiring constant infusions of capital to retain consumers’ attention, were expensive propositions. When many legacy brands began to struggle amid the so-called retail apocalypse of the later 2010s, these stores became obvious targets for cost-cutting.

Indeed, renowned tourist destinations known for shopping—Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue, Chicago’s Magnificent Mile, Miami Beach’s Lincoln Road, Santa Monica’s Third Street Promenade, and San Francisco’s Union Square-were already contending with rising retail vacancy on the eve of the pandemic.

Some of the blame here could land on the low interest rates and the overall urban optimism of the 2010s, which inflated both the pricing of buildings and, presumably, the asking rents for their retail space. Many landlords (or their lenders, or both) were simply overplaying their collective hand, long after they should have realized that their tenants were in trouble.

Also, though, a changing of the guard was afoot. Most of the legacy brands operating large flagships at the time—e.g., Gap, Banana Republic, Victoria’s Secret, Express, H&M, and Forever 21—were becoming ever less relevant to the modern consumer. A-list retailers for years, they were in the process of being supplanted.

The new crop of A-listers included some legacy brands that were managing to remain popular (left column in the chart below), but they were joined by a fast-growing crop of newer concepts (right column), many of them digitally native, that were resonating more with younger millennial shoppers and pursuing rapid brick-and-mortar expansion.

What, then, do today’s A-listers want?

Although the roster of A-listers has changed slightly in recent years, one constant has remained: instead of glitzy, multilevel showcases in globally renowned districts, the overwhelming majority of these brands now prefer more understated, modestly sized floorplates in the 1,000–5,000 square foot (93–464 sq m) range along smaller, more intimately scaled shopping streets.

In most large downtowns, however, the primary retail corridor is a vestige of the late 1800s and early 1900s, when department stores reigned supreme and square footage was also needed to store inventory, resulting in a surfeit of bigger floorplates. A wave of development since the 1990s favored larger spaces, as well, to entice the expanding categories of the era, such as urbanizing category killers and large-format drugstores.

Layered atop this mismatch has been the growing sense, since the 2010s—grounded at first in an ultimately mistaken assumption of the online channel’s inherent superiority, but also reinforced by the societal impulse for instant gratification—that retailers would need to expect less from destination shopping and instead “meet people where they are,” translating into a renewed focus on the places where consumers actually live.

Furthermore, many of today’s newer brands are primarily targeting the “neo-hipster” psychographic of highly educated, upwardly mobile creative professionals, who tend to favor settings and spaces that project a sanitized authenticity and patina, over ones with a bit too much polish and gloss. This mindset also helps to explain why even those downtowns that still have enclosed malls—and hence, lots of smaller inline bays—have struggled to attract such customers.

Seeking, then, both their preferred real estate as well as the ineffable “cool factor,” A-listers have in almost all cases been compelled to look beyond downtowns to the central spines of established neighborhoods where shoppers have long headed for fashion, or to the new mixed-use enclaves rising in former industrial quarters, where enough room exists to create such a critical mass from scratch.

Where such alternatives are located nearby, one need not venture far from some downtown’s clutch of vacant flagships to find a cluster of the industry’s latest and greatest. Consider San Francisco’s Hayes Valley, little more than a 20-minute walk from the city’s distressed Union Square shopping precinct; Chicago’s West Loop, separated by a single neighborhood from the struggling Magnificent Mile; or Santa Monica’s Montana Avenue, to the immediate northeast of the troubled Third Street Promenade.

Indeed, the exception proves the rule: the rare downtown that does not have to compete with other such districts in close proximity for these retailers is more likely to draw and maintain their interest. In Center City Philadelphia, for instance, the three-block Rittenhouse Row boasts not only the smaller floorplates reflective of its 19th-century urban fabric but also existing cotenancy that towers over all of the other shopping streets throughout the city. For these reasons (as well as Center City’s enviable residential densities), Rittenhouse Row has welcomed a slew of A-listers in recent years, despite the sluggish recovery in the West Market/JFK office core just two blocks away, as well as ongoing concerns about social disorder.

Looking ahead

Rittenhouse Row might be an anomaly, yet there are reasons to believe that the coming years could be more upbeat ones for other high-profile downtown shopping streets.

Indeed, large floorplate spaces in such settings have not fallen completely out of favor, particularly among international brands, which might see opportunity in a perceived over-reaction by U.S.–based retailers. Luxury fashion conglomerates, such as LVMH, Kering and Richemont, have been doubling down in select markets, whereas Aritzia, Abercrombie & Fitch, Zara, Uniqlo/Gu, H&M, Primark, Ross, Target, and Whole Foods are still committed, closing some stores yet opening others. Surprisingly, they have been joined by such suburban staples as IKEA and Kohl’s.

Meanwhile, a growing number of large-format experiential and “eatertainment” concepts have been helping to fill some of the void: Life Time, Dave & Busters, Puttshack, IT’SUGAR, Starbucks Reserve Roastery, Eataly, City Winery, Chotto Matte, and the Museum of Ice Cream, though many of them tend to opt for less expensive upper-floor spaces.

Obviously, current interest has not been enough to reduce exceedingly high vacancy rates, yet the pool of prospective tenants should deepen further as buildings acquired during the exuberant 2010s start to trade hands at steep discounts. Once properties reset to a lower basis, flagship spaces can be offered at reduced rents, subdivided into smaller bays, or both. If multistory, their second or third floors can be converted to other uses.

Moreover, just as A-list brands have abandoned or eschewed large floorplates in the commercial core during the last decade, they could return to them en masse in response to shifting market dynamics, consumer preferences, business models, or some mix of the three, especially if—or when—occupancy costs start to moderate. After all, the only constant in retail is change.

Indeed, downtown flagships, which offer opportunities to build and reinforce a brand in highly visible locations with heavy footfalls of free-spending tourists and affluent city residents, still seem like worthwhile investments even in a digital-first context, as the challenges and costs of online customer acquisition and retention continue to escalate.

In the meantime, planners should be careful not to forestall such possibilities by allowing for too much flexibility. Diversifying the mix with some food, beverage, and entertainment is one thing, but opening the floodgates to irreversible nonretail uses—as some cities have done or are considering—could jeopardize the fragile critical mass that underpins the appeal of major shopping destinations to customers and to prospective tenants.

One final point, on consumer demand: although downtown properties might need to be converted/redeveloped to accommodate different uses and higher densities upstairs, the resulting (incremental) increase in potential customers will not single-handedly revitalize the retail offer. Ultimately, the prospects at street level will depend on the full recovery of leisure tourism, particularly from abroad, as well as on continued densification of the citywide trade area.