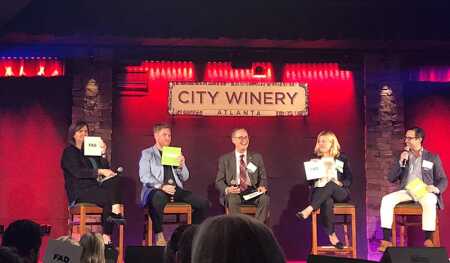

From left to right: Carol R. Naughton, president, Purpose Built Communities; Lawrence Gellerstedt IV, vice president of real estate, WeWork; Robert F. Dallas, attorney, Buckley King; Malloy Peterson; senior vice president, Selig Enterprises; and Gene Kansas, founder of Gene Kansas Commercial Real Estate; speaking on which trends they think are fads and which are here to stay at a recent ULI Atlanta event.

While the Atlanta region has grown dramatically in the last decade, the city’s traffic ranks as the eighth-most-congested among world cities evaluated by transportation analytics firm INRIX. This issue hung over much of the discussion at ULI Atlanta’s Trends in Real Estate 2019 event, held in November, which also touched on the findings from Emerging Trends in Real Estate ® 2019, copublished by ULI and PwC.

“We have a very good region, but I think it’ll be a great region when we connect it well,” said Robert Dallas, an attorney with Buckley King and planning commission chair for the city of Dunwoody, a northern suburb of Atlanta.

Dallas, who spoke on a panel with other local experts, said that Atlanta cannot fix its traffic. But as the city’s economy continues to flourish, leading to more development, there should be a focus on land use policy and density to make public transit work—and make sure that traffic doesn’t worsen as the city gains population.

Right now, Atlanta is embarking on several major transit projects, taking its transportation future in its own hands. MARTA, the transit authority that runs rail and bus service, approved in October a $2.7 billion expansion, the city’s largest in decades. The plan will add 29 miles (47 km) of light rail, three arterial rapid transit routes, and 13 miles (21 km) of bus rapid transit (BRT) lines.

BRT will be especially useful for developers, Dallas said.

“Every one of their stops, which is more transit-oriented than a typical bus stop, allows for development opportunity,” he said, adding that BRT will expand throughout the region in the coming decades.

People often tout that BRT allows for more flexibility than fixed rail, but Dallas said that if it’s flexible, it will not attract development. Having permanent stations is key.

“I’m not just talking about a stick in the ground,” he said. “I’m talking about a platform. I’m talking about a route where for, let’s say, 10 to 12 miles [16 to 19 km], we’ve invested $30 to $50 to $60 million on that route. It’s not changing overnight.”

Affordability is another major concern in Atlanta. It has the highest rate of income inequality among big cities in the United States, according to the Washington, D.C.–based Brookings Institution.

Affordable housing is critical, but Atlanta has not done much in the last decade to increase its stock, said Carol Naughton, president of Purpose Built Communities, a community revitalization nonprofit organization.

“The best way to deliver affordable housing is in a mixed-income environment, so we’re no longer isolating or marginalizing low-income families and [we’re] creating platforms for them to be able to move forward in an economically diverse community,” she said.

Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms pledged $1 billion toward affordable housing. Through an effort called HouseATL, which is a public-private and philanthropic collaborative advancing affordable housing strategies in the City of Atlanta, recommendations point to the need to produce approximately 20,000 units (new and preserved) over the next eight to 10 years. ULI Atlanta is staffing that effort. Naughton said that HouseATL has been a good start, but the city also needs developments in a range of prices, not just high-end properties.

“If we build at all the different price points, that’s going to provide a little more relief on the affordable side, even without additional subsidies,” she said. “We’ve got to think about the housing market in its entirety and building to that entire housing market, and that’ll create some flexibility on the lower end.”

Naughton said that cities surrounding Atlanta, such as affluent Sandy Springs, have reached out to Purpose Built Communities to help create housing for low-income workers. Cities have found that workers cannot easily reach jobs there.

Affordability doesn’t end with housing. Developers should also consider affordable office space, said panel moderator Gene Kansas, founder and president of Gene Kansas Commercial Real Estate.

“If we don’t have small businesses that can afford to be where the action is, so to speak, I think we’re going to miss out on a lot of diversity and richness of life,” said Kansas, also founder of Constellations, a civic shared workspace.

Coworking in general continues to be a growing component of Atlanta’s real estate market, said Lawrence Gellerstedt IV, vice president of real estate for WeWork coworking space company. Atlanta will serve as WeWork’s southern hub.

“Real estate is going to continue to change,” Gellerstedt said. “We’re going to continue to blur the lines between where we live, work, and play. As tired as that is, it’s just going to keep going.”

This is made possible by a focus toward amenities. Popular amenities nationwide include a full-service cafeteria and a fitness center, said keynote speaker Mitch Roschelle, partner and business development leader at PwC. Roschelle is also a contributor to Emerging Trends in Real Estate® 2019, produced jointly by ULI and PwC.

“The amenities of the past—the shuffleboard court, the rusty basketball hoop in the parking lot are not the amenities of today,” Roschelle said. “There’s tremendous demand to differentiate yourself with amenities.”

Major real estate company Selig Enterprises focuses on the same trend as it builds across Atlanta.

“The traffic is so bad, and transportation’s not quite there yet,” said Malloy Peterson, senior vice president at Selig Development Company, a subsidiary of Selig Enterprises. “People literally want to look around them wherever they are, and they want to see a place that they can send their kids for daycare, places they can eat lunch, dinner, get drinks, get their brunch. We don’t like to be more mobile than we have to be.”