Oak Street, located at the north end of The Magnificent Mile, is a thriving retail district of boutique stores. Encouraging smaller-format retail stores to turn the corner from Oak Street on to Northern Michigan Avenue, and attracting local, uniquely Chicago merchants to fill them, will provide a distinctive character to the north end of the Magnificent Mile, according to a ULI Chicago panel report. (ULI Chicago)

After suffering through a devastating pandemic, Chicago’s Magnificent Mile is poised for a major makeover. But it will take time, energy, and significant investment.

For decades, the storied North Michigan Avenue shopping district (also known as the “Mag Mile” locally) has been a key engine driving downtown Chicago’s economy. Stretching from the Chicago River north to Oak Street, the boulevard is a longtime jobs generator, one of the city’s top tourist draws and a major source of sales and property tax revenue. It’s in the same league of retail high streets such as Fifth Avenue in New York, Union Square in San Francisco, and Lincoln Road in Miami.

But the area is looking threadbare today after the loss of some major retailers, including Macy’s, Gap, and Uniqlo. Signs of financial distress are emerging, too. Brookfield Property Partners, the owner of the iconic Water Tower Place mall, recently decided to hand the property over to its lender, giving up on its turnaround plans for the mall.

The boulevard was already slumping before COVID-19’s arrival, but its decline accelerated as restrictions to contain the pandemic kept many tourists and office workers out of stores. Rising downtown crime has hurt the street’s image, too. The Mag Mile’s vacancy rate jumped to 26 percent last year, up from 15 percent in 2019, according to Cushman & Wakefield.

Now, city officials and Mag Mile leaders are trying to lay the foundation for a turnaround after the release of a report from a panel convened by the Urban Land Institute’s Chicago district council. The 31-page report offers a variety of solutions, including streetscape enhancements and new branding initiatives. The panel’s boldest idea: the construction an eye-catching pedestrian bridge over DuSable Lake Shore Drive that would connect the north end of the boulevard to the lakefront.

But the report stresses that reducing crime should be the top priority. Recent carjackings and smash-and-grab thefts have alarmed residents, businesses, and would-be visitors. The panel interviewed 60 people with a stake in the Mag Mile. Every one of them named crime and safety along North Michigan Avenue as their top concern, according to the report.

“Without a more concerted effort to reduce actual crime and the perception of it, any revitalization strategies are not likely to have a significant impact,” the report says.

To deter crime, the panel recommends that the Chicago Police Department increase its visibility on the avenue, with more officers on foot or horseback. The department could strengthen its collaborative policing agreement with Northwestern University, which has a large downtown campus just east of the Mag Mile, according to the panel. More security cameras could also help, as could a marketing campaign to counter the narrative that Michigan Avenue is unsafe, the report says.

The panel was blunt in pointing out the retail strip’s other big problem: Its retail mix is too stale and homogenous to attract tourists in the e-commerce era.

“Most retailers on North Michigan Avenue can be found in any sizable suburban mall, and merchandising is largely identical to what shoppers can find elsewhere, including online,” the report says.

That may be starting to change. With many traditional retailers scaling back their brick-and-mortar presence, some Mag Mile landlords are embracing new experiential concepts: immersive shows and exhibits that are part museum, part entertainment. In a former Forever 21 store at the Shops of North Bridge mall, “Prince: The Immersive Experience,” an exhibit about the music and life of the late rock musician, opens in June, following successful shows in the same space about The Office and Friends TV series. Another experiential tenant, The Museum of Ice Cream, will open this summer in the retail space at the base of Tribune Tower.

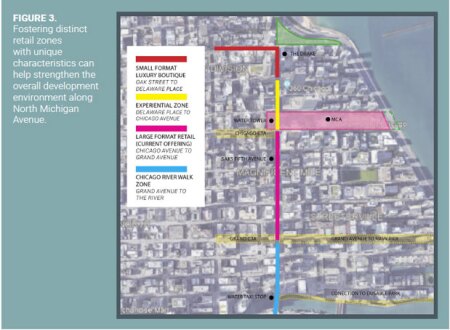

The ULI panel recommends that Mag Mile landlords divide up the boulevard into distinct retail zones. Experiential attractions, like virtual reality theme parks, immersive exhibits, and other ticketed experiences, would congregate around the middle section of the strip. Small-format luxury retailers could gather at the north end, connecting to Oak Street, the city’s swankiest retail destination, with large-format retailers on its south end.

The pandemic has been tough on other big-city shopping districts, too. The direct vacancy rate for ground-floor retail space in Union Square jumped to nearly 26 percent in 2020, up from about 14 percent in 2019, according to a report from the Union Square Alliance, which promotes businesses in San Francisco’s Union Square neighborhood.

With its wide sidewalks, North Michigan Avenue is an easy way for pedestrians to get quickly from Point A to Point B. That’s another problem, according to the ULI panel.

“There are few places to sit and eat, or simply linger and people-watch,” the report says. “There are also few spaces to accommodate public art installations or programming such as musical performances and pop-up food vendors that would attract people to The Mag Mile.”

To encourage visitors to stop, relax and eat, the panel recommends the installation of new seating and other sidewalk furniture, along with “pocket plazas.” To create a better connection to the street, landlords could modify their buildings with floor to ceiling windows and indoor/outdoor spaces for retailers and restaurants.

“Doing so would ‘erode the wall’ at the street level, visually connecting the street to the buildings along it and creating a lively, inviting environment for customers and passers-by,” the report says.

Led by Alicia Berg, an assistant vice president at the University of Chicago and former Chicago planning commissioner, the 11-member technical assistance panel included local professionals in planning, architecture, law, and real estate. The group met for a two-day brainstorming session in late October and released its report in March.

The ULI panel didn’t hesitate to dream big. It suggests the city explore the creation of a major “public common” to the east of the city’s landmark Water Tower on Michigan Avenue, a new open space for performances and programs. To make an architectural statement at the north end of the Mag Mile, the city could sponsor an international design competition to design the pedestrian bridge over DuSable Lake Shore Drive.

“A bridge that cantilevered over the top of The Magnificent Mile before turning towards the lake would offer a stunning view of The Avenue and its historic architecture,” the ULI report says.

Yet big ideas cost money, and a bridge at the north end of Michigan Avenue could run into the eight figures, says Kimberly Bares, president and CEO of the Magnificent Mile Association, which promotes businesses on the avenue.

“That’s a beaucoup bucks kind of project—that’s a Pete Buttigieg kind of ask,” she says, referring to the U.S. Secretary of Transportation.

To generate revenue for other Mag Mile initiatives, the Chicago City Council has already approved one of the panel’s recommendations: to create a special service area, or special taxing district. But the SSA runs for just three years and will only raise $742,000 annually.

That’s not a lot compared with the public funding that supports big shopping districts in other cities. The Union Square Alliance receives more than $6 million in tax revenue annually to fund its budget, while the Fifth Avenue Association, a similar organization in New York, receives more than $3 million. Both operate as business improvement districts, or BIDs—groups of property owners that agree to pay higher taxes to raise money for initiatives within their boundaries.

Mag Mile Association, which funds its operations through member dues and events rather than tax dollars, has a budget of about $3 million, Bares says.

To create a bigger and more permanent source of funding to support the Mag Mile, the city is seeking approval from the state of Illinois to create a Michigan Avenue BID that would replace the SSA.