The city of Detroit used an online platform to get more community feedback on the city’s first Sustainability Action Agenda. In addition to traditional community outreach, community members were solicited with a multilingual campaign using text messages, a web platform, and traditional yard signs, helping the city gather input from thousands of respondents, more than would be possible at a traditional community meeting.

Questions such as “What are things you would change about your everyday life—and why?”; “What do you like about your neighborhood—and why?”; and “What’s your most challenging housing expense—and why?” seem simple.

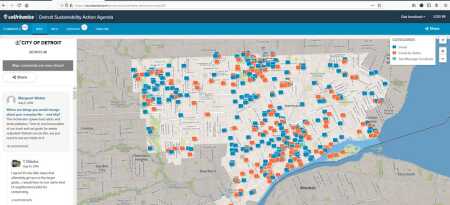

But when Detroiters answered, their responses were mapped out and indexed digitally on an all-access interactive map. The coUrbanize platform in Detroit drew over 1,300 comments and questions, part of a goal to reach nearly 7,000 Detroiters in developing the sustainability master plan. The coUrbanize website drew more than 550 followers, each receiving an email digest of comments and a summary on a weekly basis.

Using coUrbanize “was a great adjunct platform,” said Joel Howrani Heeres, Detroit’s director of sustainability. It was a good way to engage residents where they’re at, to foment discussion about what could happen.

“The cool thing about those folks we did get through coUrbanize is that we had repeated engagement with them,” said Heeres. “With other people, it was more of a one-time engagement.”

The Detroit engagement project is one of nearly 400 designed by Boston-based coUrbanize, founded by city planner Karin Brandt in 2014. Such community engagement platform companies—such as MySideWalk.Com out of Kansas City and Placespeak.Com out of Vancouver—are helping municipalities, civic organizations, and private developers gauge community needs and desires.

Brandt said that she started coUrbanize because of her experience in attending community meetings to explain developments and strategy.

“It felt like those who tend to show up at a public meeting were more opposed to change. It’s difficult to get new people to attend a meeting at 7pm, when often they’re too busy, or don’t have the time or resources,” said the Iowa-bred Brandt.

“How do we make the conversation more constructive and easily accessible to encourage a broader audience to participate?” Brandt asked. “How do you reach that population whose voice isn’t normally being heard, and get it before it’s too late to incorporate feedback?”

One of the goals also was to make it easier for immigrants in neighborhoods and ethnic enclaves to more easily communicate their views, even if English was not their first language.

In Detroit, city officials planted lawn signs with volunteer households asking passersby to text their answers to questions, written also in Spanish and Arabic. “We’re working on creating a healthier Detroit for generations to come. Get involved!” read the lawn signs.

In Detroit, the lawn signs did not generate big numbers, probably because of low foot traffic and visibility. But coUrbanize signs with questions helped galvanize community input in 2018 for developer JBG Smith Properties in designing the Central District for the Crystal City neighborhood of Arlington County, Virginia, near Washington, D.C. The Crystal City signs were in areas near subways with high-pedestrian traffic.

Among the Crystal City questions were the following:

- “What kind of restaurant would you visit most often at the corner of 18th and Crystal?”

- “What do you want to see when you leave the future Metro exit at 18th and Crystal?

- “What kind of activities do you want to see most in a future plaza at 18th and Crystal?”

“The coUrbanize platform stimulated community input,” says Andrew Van Horn, JBG Smith’s executive vice president.

“With a project of this scale and this much potential development, we really wanted to find new opportunities to access community members who couldn’t show up at board hearings and wait six hours to testify,” said Van Horn, speaking to the Washington Business Journal (Link).

Deploying platforms such as coUrbanize does not do away with face-to-face town halls on development, Brandt says. In Detroit, Heeres also used coUrbanize to gauge audience reaction to ideas at community meetings.

By using texting feedback at meetings, Brandt says that leaders get a more “democratized” process that better answers whether planners “are getting what people really think or just those confident enough to use the microphone.”

The Detroit team used the same SMS integration to display the sign questions at public meetings on the projection screen and received a lot of response from community members, says Brandt, and “we now recommend this as a best practice to all project teams.”

Detroit touts its Sustainability Action Agenda as “a strategic roadmap . . . to create a more sustainable Detroit where all Detroiters thrive and prosper in an equitable, green city; have access to affordable, quality homes; live in clean, connected neighborhoods; and work together to steward resources.”

On the coUrbanize website, residents had a lot to say about air quality, mobility issues, about improving bus stop shelters.

When Detroit’s Sustainability Action Plan was released in June, it listed multiple goals. Among them are transforming the city’s abundant vacant lots, reducing waste sent to landfills, making it easier to get around the Motor City without a motorized vehicle, and to improve air quality and reduce exposure to pollution. In Detroit, the coUrbanize platform drew multiple comments about air quality.

Even before the sustainability plan was released, one goal for cleaner air got a boost. Numerous coUrbanize comments in 2018 came from residents disgusted by odors released by an incinerator near the heart of the city.

“The incinerator spews bad odors and emits pollution. Time to end incineration of our trash and set goals for waste reduction! Detroit can do this, we just need to set our minds to it,” said one website respondent.

In March, the operators of the controversial Detroit incinerator, which had run afoul of government regulators for years, announced it was ceasing operations in response to financial concerns and community outrage.

In some communities, the time of day of a meeting might not be convenient for work or child care needs, or people would have to travel long distances to participate. By reaching out to people on their phones or by street signs, communities are giving a voice to the people who are often left out of the traditional community meeting process.