No ordinary street fair, this new generation of urban festival draws on the ideas—and donations—of internet-empowered masses to help cities shape their image.

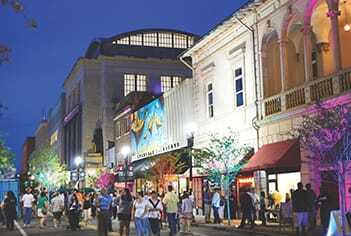

In April, 130,000 people flocked to the first One Spark festival in downtown Jacksonville, Florida, to hear indie rock bands, watch fire dancers, admire multimedia art installations, and, most important, listen to entrepreneurs’ pitches for more than 400 projects in search of seed money. The ventures ranged from art and theater projects to robotics and video games, and included a few projects that were so edgy that they defied categorization.

One competitor sought funds to transform a bland local water tower into public art by emblazoning it with a giant flamingo and then auctioning off corporate naming rights to it. Another participant touted Riverpool, a giant floating concrete swimming pool and marina that he wants to put in Jacksonville’s St. Johns River. Yet another proposed building something called the Jacksonville Eco Village for Green Urban Rehabilitation, which would combine environmentally minded home renovation, solar power, and urban gardening.

Related Content: How to Build a Better Crowdfunding Festival: Lessons from One Spark

It was a surprising display for a city better known as a transportation hub, river port, and financial center than as a hotbed of edgy artists, high-tech wizards, and envelope-pushing social entrepreneurs. That image is one local visionaries such as Elton Rivas, a 35-year-old marketing consultant and cofounder of the event, aim to change through the One Spark festival, planned as an annual five-day event to brand Jacksonville as the next Austin or Seattle. “We got tired of people telling us that we had to move to another market to do something creative,” Rivas explains.

It was not just the exotic projects on display at One Spark’s inaugural festival that made it cutting edge. Organizers promoted One Spark as the world’s first community festival focused on crowdfunding, a nascent method of microfinance in which small contributions are solicited from large numbers of benefactors via the internet.

One Spark raised $107,000—a little more than 10 percent of its $1 million budget—from more than 400 backers, some of whom contributed as little as $10, using the popular crowdfunding website Kickstarter. Jacksonville resident Peter S. Rummell, immediate past chairman of ULI, provided the remainder, plus another $250,000 for prize money.

Visitors to the festival could download a crowdfunding app to their mobile phones that not only allowed them to vote for entrants competing for a share of that prize money, but also allowed them to register an account and contribute on the spot to an exhibitor whose idea caught their fancy. The take from such direct contributions was small—Rivas describes it only as tens of thousands of dollars—but the opportunity helped reinforce the festival’s interactive allure. “It’s sort of like Kickstarter, but in person,” Rivas says.

The Jacksonville event may be one harbinger of a promising new international phenomenon—civic festivals that aim to promote local communities by incorporating crowdfunding both as a source of capital and as a tool for engaging visitors and residents.

In some cities, festival promoters are using piecemeal online solicitations to cover some or all of the startup and operating costs. Others are seeking to transform existing festivals into de facto crowdfunding events by helping creative exhibitors obtain financial support online. And some are setting out to do both.

Like any method of raising money, crowdfunding comes with caveats and potential pitfalls, and its novelty means users must be willing to venture into largely unexplored territory. But proponents say that crowdfunding festivals’ potential to attract large, far-flung audiences and to synergize the online social networking with a tangible event makes them a powerful tool for building a distinctive community brand. Indeed, some of the concept’s enthusiasts even foresee a not-too-distant day in which architects and developers may use crowdfunding festivals to help remake a city by garnering support for new buildings or redevelopment projects.

Crowdfunding and Branding Converge

Though crowdfunding is a contemporary phenomenon, its roots may go back to the 1880s, when newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer staged a campaign that raised $100,000 from small donors to complete the pedestal for the Statue of Liberty. It drew 125,000 New Yorkers as participants, most donating less than $1.

The rise of the internet has made raising money a few dollars at a time vastly more feasible. By the late 2000s, crowdfunding websites such as Kickstarter.com, ArtistShare.com, and IndieGoGo.com were enabling filmmakers to make movies and musicians to record CDs without corporate backing by soliciting contributions directly from fans. Those pleas proved so successful that arts institutions, neighborhood organizations, and even companies began eyeing the crowd for financial support. For example, the Smithsonian Institution’s Freer and Sackler art galleries recently sought $125,000 from small donors via the cause-oriented crowdfunding site Razoo.com in order to fund an exhibit on art related to yoga. “It’s another way for us to tap into veins of support out there,” explains Smithsonian spokeswoman Allison Peck.

By 2012, according to Venture Beat, the number of crowdfunding campaigns worldwide had risen to 1 million, and they raised $2.67 billion. Massolution, a research firm that follows crowdfunding, predicts the volume will nearly double this year to $5.1 billion.

Up to this point, people who contribute to crowdfunding efforts generally have had to be content with receiving small tokens of gratitude—a T-shirt or a music CD, for example—in exchange for their contributions. But now, thanks to a federal law passed by Congress in 2012, startup companies eventually will be able to sell small shares of equity to the crowd as well, providing them with an early-stage opportunity that once was available only to high-net-worth investors. (Before such investments may take place, however, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission [SEC] will have to issue new regulations. As of July 2013, the commission had not yet done so.)

Crowdfunding’s rise has dovetailed with another movement—local art, music, and technology festivals that help brand communities as innovation centers and attractive destinations both for the youthful creative class and the businesses and investors that can help them achieve their ambitions. Not surprisingly, many festival promoters are trying to leverage crowdfunding’s benefits.

Most are small-scale efforts—a few thousand dollars for a local comedy festival in Jersey City, New Jersey, for example. But others are more ambitious, such as the Kickstarter campaign by Durham, North Carolina’s Art of Cool Festival to raise $25,000 to stage performances by jazz musicians and “get people thinking about what is important and worth preserving in downtown Durham and encourage them to invest in the places they live,” according to the event’s Kickstarter pitch. In Portland, Oregon, promoters of the XOXO Festival—a three-day “celebration of disruptive creativity” that showcases musicians, filmmakers, comic book artists, game designers, and electronic hardware tinkerers—raised $176,000 of the staging costs for its September 2012 event via Kickstarter.

“A lot of people think we did this festival to spark downtown, but the issue is really bigger. If we can create a sense that Jacksonville is a place where ideas and money can meet, we’ve really got something.”—Peter Rummell

Meanwhile, other established community branding festivals are incorporating crowdfunding into their programs by helping exhibitors raise money from the crowd online. The most conspicuous example is Austin’s South by Southwest (SXSW) festival—a 26-year-old event that has grown in scope to showcase not only local music, but also films and emerging digital technology—which is underwritten by major corporate sponsors such as AT&T, Yahoo, and Esurance. The 2013 edition of SXSW featured an expert panel on the benefits and legal hurdles to be overcome in using crowdfunding, and keynote speakers such as OUYA Inc. chief executive Julie Uhrman, whose business raised $8.5 million via Kickstarter to finance development of a small game console designed to run on the Android operating system.

At San Francisco’s Launch Festival, an event this past March that showcased startup companies, organizers provided a mobile phone app that allowed 6,000 registered attendees to spend “launch dollars"—essentially, IOUs for funds to buy equity stakes in the ventures of exhibitors whose products they liked—when the SEC finally gives regulatory approval for such deals. The app also gave cloud participants a chance to see, in real time, which startups were attracting the most future investment.

Branding a Community

Crowdfunding experts say Jacksonville’s One Spark festival seems to have been the first community-branding event built around crowdfunding, not only raising at least some operating capital from the crowd, but also providing a platform through which exhibitors could raise funds. Already, communities such as the Kansas City metropolitan area and Jackson, Mississippi, reportedly are moving quickly to set up similar festivals, and there is interest in Canada and the United Kingdom, according to Sydney Armani, founder of Crowdfundbeat.com, a website that covers the field. “You’re going to see a lot of this sort of thing,” he predicts.

One appeal of crowdfunding festivals, says Rummell, is that they can be powerful tools for building a community brand—not just for the outside world, but for people who live in the community. It is worth noting that nearly 86 percent of the people who attended One Spark came from the city itself, and another 7 percent hailed from nearby communities in north Florida. “Jacksonville is like a lot of medium-sized cities in the million-plus range,” Rummell explains. “There’s a surprisingly large group of bright 25-to-35-year-olds who want to stay here and are looking for reasons to do it. But they’re also looking to make a living in their field. They want to have a place that’s contemporary, that’s with it.”

He says that a crowdfunding festival also can help forge a community connection between two groups that are often separated by age and economic means—the real estate and development sector, and the art and technology creative class. “A lot of people think we did this festival to spark downtown, but the issue is really bigger,” he says. “If we can create a sense that Jacksonville is a place where ideas and money can meet, we’ve really got something.”

There also are plenty of ancillary benefits for property owners and developers. The same mobile app that allows festival-goers to vote for and contribute to exhibitors also can provide a curated tour of a downtown area. Festival organizers can subtly guide visitors to areas and structures that they want people to see—and in the process, reshape public perception of the city itself.

It is not just the exhibitors, but the places where they exhibit that are on display, Rummell notes. One Spark organizers placed some exhibits inside existing businesses such as restaurants, and put others inside vacant space in buildings available for leasing. “It created a lot of foot traffic into those spaces,” Rummell says. For local merchants, that translated into a big short-term bump in revenues, and there is the possibility that potential tenants may discover spaces they were not aware of previously. On the horizon lies the tantalizing template of SXSW, which organizers calculate pumps $126 million into the Austin economy each year.

The next One Spark, scheduled for April 2014, will provide even more opportunities for exhibitors to obtain financing for their projects. In addition to $200,000 in prize money that will be distributed according to visitors’ votes, the festival’s organizers will award $10,000 prizes to winners of juried competitions in art, innovation, music, science, and technology categories. Organizers also say private investors and equity firms will make millions in additional potential funding available to exhibitors.

Although the concept of local crowdfunding festivals is just starting to take off, some experts in the field already are imagining ways to leverage and expand the concept. So far, such local events have showcased mostly the arts and technology, but Elizabeth Smith Kulik, cofounder and chief executive of crowdfunding site Prohatch and a 35-year real estate industry veteran, expects future festivals to include architects and builders as well. “There are [development] projects that you might have difficulty getting institutional investors for,” she says. “There’s a difference between Wall Street and Main Street.” (Though such deals would be subject to extensive SEC regulatory scrutiny, a recent Washington Post article notes that some conventional capital-management fund managers are skeptical about whether crowd investors have the expertise to evaluate real estate projects for their viability.)

Dan Marom, an Israeli crowdfunding expert and author of the 2012 book The Crowdfunding Revolution: How to Raise Venture Capital Using Social Media, would even like to see American communities finance public projects in part through crowdfunding—a concept already being tried in the Netherlands, where a pedestrian bridge through Rotterdam is being built with crowd contributions. Contributors will have their names listed on the bridge’s beams as a reward. “Crowdfunding [festivals] could be a very powerful mechanism for civic empowerment,” he says. “It’s a way for citizens to vote about ideas, to engage, and make a dialogue.”

But Marom, who gave a talk at One Spark, already sees crowdfunding festivals as a powerful tool for using the power of the internet and social networking to build a local brand. “You take one step ahead and move things into the offline world,” he says. “Instead of just reading about entrepreneurs on the web, you can see them for real. And then you can continue the conversation.”