From 2007 to 2011, jobs grew faster in many downtowns than in surrounding areas, reversing a nearly 60-year-long trend in the United States. This is according to research by economist Joe Cortright of the City Observatory, a think tank based in Portland, Oregon, funded in part by the Knight Foundation.

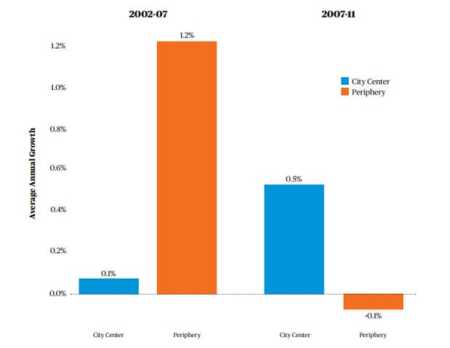

The report—Surging Center City Job Growth—found that between 2007 and 2011—the years of the onset of and early recovery from the Great Recession—employment in downtown areas, broadly defined, grew 0.5 percent annually, while in the surrounding metropolitan areas, it dipped by 0.1 percent annually. City centers outdid surrounding areas in 21 of the 41 metropolitan areas examined. In only seven cities did the surrounding region outperform the urban core.

Three Sun Belt cities recorded the fastest growth rates in their urban cores. Jobs in downtown Austin, Charlotte, and New Orleans increased at rates of 3.4, 2.5, and 2.1 percent per year, respectively, outstripping their outlying areas.

By contrast, in the preceding five years (2002–2007), dispersal of jobs was still the norm. Employment in city centers was stagnant but in outlying areas was growing—actually about 12 times as fast (0.1 percent versus 1.2 percent).

The report points to two factors driving the recent centralization of jobs. First, the shift in employment to knowledge- and service-based industries. These tend to be located in city centers that facilitate face-to-face interaction and have outperformed other industries in job growth. By contrast, manufacturing, construction, warehousing/distribution, and transportation are more scattered and have performed less well.

Still, Cortright says, this difference alone did not account for city centers’ job growth. City centers also displayed a competitive advantage, turning the tables on the suburbs, which had long exceeded downtowns in attracting and creating jobs. This has been especially true in the arts, entertainment, dining, lodging and finance, insurance, and real estate.

Cortright points to the growing movement of talented young workers into urban neighborhoods, something that may help explain the new competitiveness of city centers. “The growing attractiveness of urban living,” he writes, “is leading to measurable increases in skill level of the labor force near city centers. Employers are taking notice: a growing number of firms report that they are choosing downtown locations in order to tap into the growing talent pool of young workers.”

The resurgence in city center jobs has not been universal, he notes. Job decentralization has persisted in some places. Six metropolitan areas exhibited much stronger job growth in outlying areas than the urban core in 2007–2011 as well as in 2002–2007: Houston, Kansas City, Las Vegas, Louisville, Rochester, and San Antonio.

The question, of course, is whether the recent job figures favoring city centers are permanent or transitory. Cortright sees a number of longer-term, structural reasons for optimism about job growth in the urban core during the current economic expansion. Besides the lure of urban living for well-educated young people and the movement of companies to city centers to tap this labor pool, he cites the growth in the urban core both of consumer industries—lodging/food services, arts, entertainment, and recreation—and the education and health care industries. He also points to the continuing relative decline of manufacturing and distribution, whose jobs are concentrated in outlying areas, and the waning of major investments in new highway construction that has long propelled the dispersal of people and jobs.

Aaron Renn, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, credits the report for being measured rather than overselling its findings. It is good news for cities, he says, though the findings are uneven. Job growth is concentrated in certain cities, and the period of change is limited. The recent past, he says, is not a complete indicator of the future, but it cannot be dismissed.

Renn likens the situation to that of traffic, which, he says, had declined nationally from 2007, when the recession began, until last year, when it rose slightly. The question, he says, is whether traffic will resume growing or if something is going on.

Cortright says one blogger was unimpressed by his findings, pointing out that job growth was stronger in city centers in barely half of the 41 metropolitan areas and that the job gains did not offset losses in the previous five years. In other words, Cortright says, the blogger “was saying the glass was half empty, not half full.” In fact, he adds, “the glass used to be pretty much close to empty.”

Wendell Cox, principal at the firm Demographia, calls the job changes “miniscule” and says that little could be divined from a study of “the worst four years of economic performance since the 1930s.” It would, he says, be like an analyst in the midst of the Great Depression trying to predict employment trends.

Superseding a 60-year-old trend, Cox says, would be a sea change, adding, “Sea changes are unusual.”

He points to newly released U.S. Census figures for the years 2011–2014 showing Americans relocating to the suburban counties in the 50 largest metropolitan areas in numbers far exceeding moves to counties containing urban cores. In the latest year studied, between July 2013 and July 2014, 230,000 people relocated to these suburban counties while 190,000 people left core counties.

“A move back to normalcy,” Cox calls it.

He points out that millennials have not only moved to city centers. “Ninety percent of millennial growth is outside the urban core,” he says. “How many people can you cram into two square miles?

“Granted, population trends are not the same as job trends,” Cox adds. “Jobs simply follow people.”