“Preservation and interpretation of the Nation’s ethnic roots reminds us that cultural diversity was and remains a significant factor in our national experience.” — Historian Antoinette Lee

An estimated 90 percent of construction will take place on existing buildings over the next 10 years. In many cases, the tax incentives available through the National Park Service (NPS) will be critical in determining a project’s viability. It is therefore incumbent on the NPS to look equitably at building inventory currently listed in the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). Of the 90,000 places registered today, less than 8 percent pertain to women, Latino, African American, or other groups. These figures give way to cultural erasure and handicap prospects of adaptive use development in communities of color.

I would like to share some of my recent experiences with the design and development of the Farley Post Office in New York City as a case study of the program’s potential, then look at ways in which the program might expand the scope of development and tax credit opportunities. Through the recent example of the Farley development, inclusive of Moynihan Train Hall, one can see how the NPS has the power to shape the public realm for the better. Having recently worked on the design side for the project, I was part of the team that negotiated the requirements with the NPS and can attest to its tangible benefits.

While the project is most widely recognized for its transportation component, the success of the Farley development project extends far beyond the singular component of the train hall. More than a transportation project, the Farley redevelopment’s victory lies in a team of stakeholders creatively reenvisioning the best and highest uses of a historic structure. At a nearly even financing split, neither the train hall nor the private development of the project could have existed without its counterparts. Though the character of the space is transformed, the planning of the building remains quite similar. The envelope, large open floor plates, and internal vehicular circulation remained as key components of the project planning, benefiting both the project’s design as well as its financing. This approach to reuse was guided in large part by the NPS, which arguably brokered the project as we see it today and shepherded it to successful completion.

The repositioning of the Farley Central Post Office is one of the largest adaptive use projects in the history of North America. It is a mixed-use development comprising class A commercial office, transportation, retail, and U.S. Post Office space spread out over two city blocks totaling nearly 1.4 million square feet (130,000 sq m). I would argue that the project was such a success due to:

- The extension of the public realm from Hudson Yards to Madison Square;

- A public/private partnership capitalizing on the common interests of the stakeholders;

- The existing building’s readily adaptable plan and envelope to both commercial and public realm uses; and

- The guidance of the National Park Service in maintaining the project’s character across different phases and interest groups.

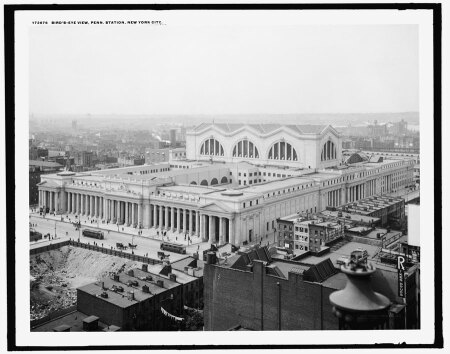

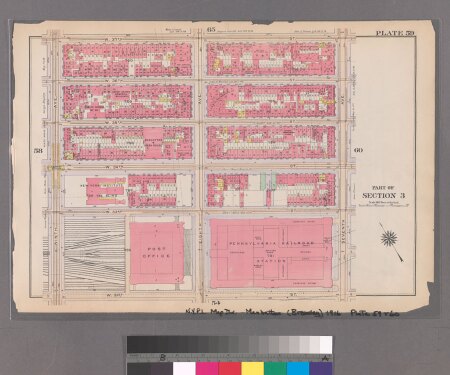

The NRHP and, by association, the NPS are inextricably intertwined with the development of the original Penn Station and its sister building, the Farley Post Office. The original Penn Station was demolished in 1963 as part of the development deal for the new Penn Plaza. In exchange for the Penn Station air rights, the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) was to receive construction of a smaller underground station at no cost, and a 25 percent stake in the new Madison Square Garden. The demolition of the original Penn Station birthed the historic preservation movement in the United States and the National Preservation Act of 1966, inclusive of the NRHP. Penn Station’s sister was recognized as a New York City landmark in 1966 and entered into the NRHP in 1973. This important designation helped shape the recent development partnership.

The original Farley Post Office was erected between 1911 and 1914 by McKim, Meade, and White as part of a proposal by the PRR. The U.S. government took title of the site in 1907, with an easement set in place for the PRR allowing for use of the tracks and platforms underneath. The first sections of the Penn Station itself were opened in 1910 as an expansion of tracks and service into Manhattan from what is today Exchange Place in Jersey City. An annex was built onto the original structure between 1932 and 1934 when the U.S. government purchased the western portion of the lot from the PRR. The addition was composed of an expanded loading dock at grade with vehicular service entrances off Ninth Avenue, 31st Street, and 33rd Street. The expansion was led by Postmaster James A. Farley, the current building’s namesake. From the outset, the Farley Post Office and Pennsylvania Station were developed in concert as an early iteration of a public/private partnership.

Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan was the first to propose the transformation of the Farley Post Office into a reimagined Pennsylvania Station in 1993. In many ways, the original Farley Post Office was well suited as a development site for the new mixed-use facility from the beginning. Physically, the original post office was designed around a large central mail sorting hall under an industrial skylight, surrounded by postal office windows above. Comprising two city blocks between 31st and 33rd streets, and 8th and 9th avenues, the building offers contiguous floor plates on a 354,000-square-foot (32,888 sq m) site ideal for campus-oriented commercial development models like those of Apple, Microsoft, or Facebook—in the middle of Manhattan. At the ground level, interconnected service entrances over 15 feet (4.6 m) wide easily lend themselves to new pedestrian retail corridors.

Fiscally, the original U.S. Postal Service tenant has been in a free fall over the last few decades. A General Accountability Office report found that the Postal Service has lost more than $69 billion over the last 11 years. As part of such losses, the facility had fallen into disrepair and began curtailing 24-hour-a-day service in 2009. The Post Office found itself in a position of no longer needing or being able to maintain almost 1.4 million gross square feet (130,000 sq m). This presented the right physical and financial common ground for a group of public and private stakeholders to take the existing 97 percent private, 3 percent public space split and transform it into what is today a 63 percent private, 37 percent public mixed-use private development and transportation hub.

These partners include the Empire State and Moynihan Station Development Corporations, Amtrak, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the U.S. Post Office, Related Companies, and Vornado as principal stakeholders. Of the many public agencies that advised on requirements for the development, the National Park Service and the tax credit program had one of the largest impacts on the public/private partnership, and the post office’s expansion into the public realm. The Farley Development, of which Moynihan Train Hall is a piece, is in fact the largest tax credit project in the history of the program.

Since 1976, the federal rehabilitation tax credit has encouraged the preservation and adaptive use of historic buildings by offering owners a tax credit. The tax credits represent a dollar-for-dollar reduction in taxes based on 20 percent of the cost to rehabilitate the project. There are four main considerations that must be met to qualify for the tax credit:

- The historic building must be listed in the National Register of Historic Places or be certified as contributing to the significance of a “registered historic district.”

- After rehabilitation, the historic building must be used for an income-producing purpose for at least five years.

- The project must meet the “substantial rehabilitation test.” In brief, this means that the cost of rehabilitation must exceed the pre-rehabilitation cost of the building. Generally, this test must be met within two years or within five years for a project completed in multiple phases.

- The rehabilitation work must be done according to the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation. These are 10 principles that, when followed, ensure that the historic character of the building has been preserved in the rehabilitation. (Source: U.S. Department of Interior)

It is the fourth point that shaped the design scope of the project and created a common set of ground rules for the various stakeholders. In the case of the phase 2 train hall, the refurbishment of existing trusses at the skylight (a hallmark of the design) were part of the negotiations with the National Park Service. Similarly, the vehicular service entrances and drive aisles were converted into pedestrian retail entrances, leaving the original organization of the facade and ground floor plan reenvisioned without major alterations. Original elevator shafts designed to transport mail from the tracks onto the sorting floor were reappropriated as Amtrak baggage elevators.

For the third phase of work, the 10 Standards for Rehabilitation guided the restoration of existing perimeter walls at the core and shell spaces. Ceiling types across the building were catalogued together with the New York State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO), which shaped exposed structural expression across the open office plans and organization of the building distribution systems. Key elements of the U.S. Postal Service layouts were preserved, including existing corridors and openings running through the otherwise open floor plans as well as elevator lobbies now serving as conference and meeting rooms. Significant entrance lobbies such as that of the U.S. Passport Office were preserved to serve as commercial office entrances, with service windows refurbished to serve as café counters.

I celebrate the success of a magnificent public space afforded by the Farley Development and applaud the part of the NPS both financially and technically. At the same time, I question why similar efforts have not been as successful in other New York City projects such as the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem or the African American Burial Ground in the Financial District. Where intervention from our public agencies has the potential to affect the cultural legacy and economy of a community, we must ensure that there is equal access to that agency.

Efforts have been made to include diverse racial and ethnic inventory into the NRHP to varying degrees since the early 20th century. In 1943, the NPS added the first-ever property associated with African American heritage to the national park system with the George Washington Carver National Monument in Diamond, Missouri. More systematically, in 1972 the NPS funded a study of sites with the express intent of expanding the inventory associated with African American heritage. That study led to the addition of 85 additional properties. More recently, preservation efforts have shifted to include a diverse voice in the selection and management of newly registered sites.

Semi-recent recognition of Traditional Cultural Properties (TCP) has looked to expand the scope of what is defined as significant with a 1980 amendment to the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 with the following:

For the purposes of the National Register, the National Park Service defines a TCP as: one that is eligible for inclusion in the National Register because of its association with cultural practices or beliefs of a living community that (a) are rooted in that community’s history, and (b) are important in maintaining the continuing cultural identity of the community.

For communities of color to have access to the cultural and economic benefits seen at the Farley Post Office, both the inventory on the NRHP and those assessing its applications must be diverse. In 1993, U.S. Representative John Lewis stated, “Historic preservation must represent every community. . . . I believe that the National Park Service lacked adequate minority representation in its programs and historic sites.” At that time, of the 47,000 entries in the historic register, only 2.6 percent were significant to minority ethnic or racial groups.

Diversifying the scope of inventory on the NRHP broadens the opportunity for development in communities of color. The post office conversion has played a pivotal role in the Penn Quarter master plan, spurring a renewed sense of pride in Midtown Manhattan’s public space. I believe this same model could have a far-reaching impact on cultural and economic development in underserved communities if the NRHP better represented our cultural diversity as a nation. Let’s applaud the victory of the Farley Development and call on our public agencies to ensure equitable access to the repositioning work ahead of us. Citing historian Antoinette Lee, “What (we) are more concerned with ensuring today is that cultural groups enunciate what resources are important to them, how the resources should be protected, and who should be empowered with the management of the resources.”