Anyone who has been involved in development projects knows how difficult it is: assembling your capital stack, navigating local zoning requirements, finding the right design and construction partners, securing any needed variances. It is a process that can be drawn out and fraught with uncertainties.

It is no wonder that many view community engagement as an additional obstacle—one, that if not otherwise required, they are inclined to skip.

On the other hand, if, like most community members, all you see of a new development-in-process is construction fencing (featuring a couple of logos, maybe a rendering), then it is understandable that you might experience a new development as a sudden loss—a part of your community, your world that is now fenced off, inaccessible. Eventually the fencing will come down, but what will be there when it does, and for whom?

Long-term residents—especially those in neighborhoods that have traditionally been deprived of investment—find themselves in a bind. On one hand, they need resources to preserve and improve their community’s housing stock and infrastructure.

A 2016 report indicated that across the United States, people are living in 30 million units of substandard housing that pose “significant physical or health hazards” (such as lead contamination, gas leaks, poor heating and air conditioning, and crumbling structures). Inequities in the built environment (inside and outside homes) contribute to vastly different health outcomes and life expectancies, leading to differences of 20 to 25 years in life expectancy between neighborhoods within the same city. And the nationwide shortage of affordable housing now stands at 7.4 million units—including more than 63,600 in Minneapolis, 40,000 in Cincinnati, 31,000 in Louisville, and 17,000 in Pittsburgh.

On the other hand, investment often means displacement. Though Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhine neighborhood, for instance, is often celebrated as a model of redevelopment, a recent report shows it has experienced a 73 percent loss of affordable units for people earning 30 percent of the area median income. (As the adjacent neighborhood, the West End, sees massive investment related to a soccer stadium, a report shows that four in 10 residents are at risk of losing their homes). It is no wonder that long-term residents often greet the news of new investment with an uneasy mixture of hope and anxiety.

This is a nationwide problem. Small to medium-sized cities across the United States—places often celebrated for their low cost of living—are increasingly unaffordable as higher-income residents from the coasts relocate. Boise is one example of this, but if you look at lists of cities that are becoming unaffordable, you see places like Charlotte, Des Moines, and Irving, Texas.

This situation may reinforce developer reluctance to engage the community in a robust manner, observing that the community either fails to show up or only shows up to say no. But for those wanting to ensure that a project will contribute to the betterment of an existing community rather than its displacement, the situation also underscores the necessity of community engagement.

Communities know what they need. Their residents understand their neighborhood’s strengths and weaknesses because they live there, navigating its difficulties and delighting in its charms. They can tell you what they love most about their neighborhood as well as share what amenities they lack, the intersections that pedestrians avoid because they are dangerous, or the perfect spot to spend a sunny day. Those who view community engagement as an obstacle risk missing out on a wealth of knowledge about what can make a project successful.

In GBBN’s health care, education, culture, and workplace projects, we regularly work with our clients to bring together robust focus groups so that our design can be informed by those who will actually use the space. They provide incredibly valuable input and help set goals to define what success for the project will look like.

If the end user is a yet-to-be-defined tenant—whether a resident, employer, or commercial tenant—developers and architects rely on experience and collected data to make assumptions. But they should also draw on the expertise of community stakeholders—neighbors, nearby businesses, neighborhood organizations—that will be affected by the development. It’s important to see them as end users as well and to bring them into the process of defining what a successful project will accomplish.

Nonfinancial stakeholders not only deserve to be heard, but your project will be improved if they are. They may not have title to the property, but their lives will be shaped by what happens there. Beyond that, they are invested in the community, they know how it works, and they can help your development team define the design problem more accurately, identify the actual needs of that user better, and assess the impact of a development on the community where it is located.

This can also benefit your development by cultivating community support, which can ease the development and permitting processes—helping secure variances or public funding—and set your project up for success once it is built by ensuring that it will meet the community’s needs. If it is not meeting the existing community’s needs, it’s worth asking who the project is for and whether it might result in the displacement of current residents.

Fostering More Robust Community Engagement

When viewed as a box to check (or worse, an obstacle), community engagement tends to take rather anemic forms—a poorly advertised, weekday meeting; a presentation to a single community group whose membership represents only part of the community; a request for a letter of support after the program and design are set.

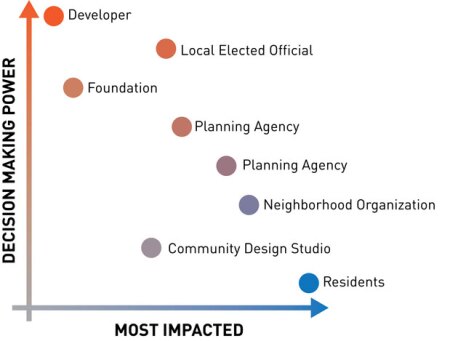

More robust community engagement—engagement that truly listens to all community members, taking care to draw out the voices of residents traditionally most removed from decision-making power (but also most affected by it)—should focus on building trust and empathy.

In our experience, we’ve found that the following considerations help cultivate that trust:

- Take pains to reach the entire community. Find different ways to reach people who are less accessible. Digital communications are easy, but they’ll miss segments of the community. Don’t shy away from distributing flyers, reaching out through existing community groups, and employing other means of being present in the community.

- Engage early. Before design has begun, before the program is fully settled, you can consult the community to see what it needs. This can help you set the right goals for your project while developing community support. For one of our Cincinnati projects, the city actually organized an engagement session as part of the request for proposals (RFP) process so the community could inform the development of a city property from the start.

- Be inclusive: accommodate different styles of engagement. Some people are comfortable speaking up in public; others are not. Provide different modes for input through writing, forums, small group discussions, and online platforms. Following the pandemic, an increasing number of people are comfortable in a digital environment and can connect in that way as well. Enterprise Community Partners and Engage Pittsburgh have some great online platforms that can help.

- Accommodate people of different abilities and social needs. A physically accessible space for community engagement events is a must. Partnering with an organization to provide child care will also allow more voices to be heard. You should also consider translation/interpretation services, where appropriate.

- Show the takeaways. Each engagement session should begin by reviewing takeaways from the previous session to confirm what you heard. It illustrates that you are listening. This is what we’ve heard. Is that correct?

- Be clear about the kind of input needed. This changes throughout the design process from a very open-ended surveying conversation style to a more directed presentation-with-question style. Be open about what can still be changed and what input is helpful.

We prefer three sessions of community engagement: one early on before design starts, one follow-up to get input on the development design and to confirm what we heard in the first session, and one to get final approval at the end of the design process. We used this approach in our College Hill Station project in Cincinnati and were able to get the buy-in from the community. Community members even held a parade to welcome the construction machinery into their neighborhood on the day of groundbreaking!

From Community Engagement to Community Empowerment

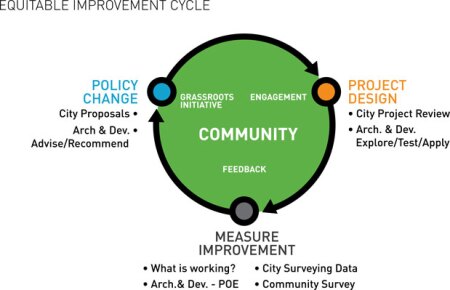

For community engagement to really succeed in fostering equitable development, it is important to help create conditions that help long-term residents share in the decisions that shape their community. This can be done to some extent by bringing community members in early and making room for them to shape a specific project. But this also requires us to move beyond the limits of traditional, project-based approaches.

Three initial steps can be taken to help center the community in development efforts.

- Build relationships before buildings. At a recent panel of developers that GBBN hosted at the Environmental Justice Symposium, part of its Design Issues Series (DIS), all the developers present stressed the importance of developing long-term relationships in their communities. As Gill Holland put it, “helicoptering” into a neighborhood with the attitude that “‘we have all the answers, this is going to be great for you,’ is not the way to do it.”

Along with Derrick Tillman of Pittsburgh’s Bridging the Gap Development, he stressed the importance of maintaining an ongoing presence in his community. Tillman even reported that he aims to be in a neighborhood for a couple of years before initiating a project there. Cultivating relationships this way will help you understand and address the needs of a neighborhood. In addition, your neighbors might even help identify opportunities you would not have known about. - Build local frameworks and knowledge for equitable development. Though community members have invaluable experiential knowledge to offer, they do not always have the most reliable information regarding equitable development trends in their city. Developers and city officials would also benefit from more fine-grained, reliable data. A number of grassroots initiatives in , Minneapolis, and elsewhere have developed rubrics to identify and measure what it means to build inclusively.

A major benefit of such tools is that they would enable better input by collecting clearer, more consistent data for measuring equitable development before and after projects are completed. This could help communities, developers, architects, and city officials achieve consensus about existing problems and potential solutions. Such data could be used to strengthen community engagement and improve city policies to encourage more equitable development. Of course, to be effective the metrics must be clear and transparent while providing enough specific data. - Put the community at the center of planning. Adopting form-based code offers another promising way of empowering communities to shape their development. The process itself brings community members together to articulate a shared vision of their neighborhood’s future. Four communities in Cincinnati have done this, defining how they want their neighborhoods to look, setting desirable density levels, and articulating guidelines for future development. This will make it easier to communicate with potential developers as the process shifts decisions about development away from a highly technical—and, at times, contradictory—set of codes to the community itself.

The last two items go beyond the activities typically associated with development. Indeed, even the task of developing long-term relationships in the community where you’re working goes beyond typical practice. But with the scale of our needs—for affordable housing, for development without displacement—it is time work beyond the typical.

An architect in GBBN’s community development market, STEFAN CORNELIS is a member of ULI Cincinnati and is active in its Young Leaders Group. STEVE KENAT is a Principal and Director of Community Development at GBBN Architects, Chair of ULI Cincinnati’s Advisory Board, and a member of the ULI Urban Redevelopment Product Council. GBBN Architects has offices in Beijing, Cincinnati, Louisville, Minneapolis, and Pittsburgh.