Catellus first developed the 72-acre (29 ha) Bayport, a community of 632 single-family detached houses. Later, it developed Alameda Landing, a 300,000-square-foot (28,000 sq m) retail center plus 253 housing units. An urban street, Singleton Avenue, runs down the middle of the retail center and into the housing sections. At top center are the so-called big whites, 22 interlinked two-story office buildings around a green mall. (Digital Sky-2018)

This article appeared in the summer issue of Urban Land on page 80.

Alameda Point is the 1,560-acre (630 ha) western quarter of the six-mile-long (9.7 km) Alameda Island, which juts into San Francisco Bay immediately south of Oakland. For six decades, from 1938 to 1997, it was a naval air station (NAS) until the U.S. Navy, as the result of the federal base closure process, gave it to the city of Alameda, which occupied the other three-quarters of the island. Through two decades, the form, face, and future of the former NAS have been emerging.

In 1996, the Navy and city of Alameda completed a three-year planning process for redevelopment of the site, which culminated in the adoption of the NAS Alameda Community Reuse Plan. In 1999, the city received from the Navy the first 218 acres (88 ha). Since 2000, the city has undertaken many plans dealing with complex issues such as groundwater and soil contamination, geotechnical hazards such as earthquakes and tsunamis, flooding hazards, existing commercial and residential leases, and historic district resources.

Catellus Development Corporation, the Oakland-based independent company formed as owner of the real estate holdings of the Santa Fe and Southern Pacific railroads and later a subsidiary of ProLogis from 2005 to 2011, sought entitlements to transform the 218 acres (88 ha) for a variety of office, retail, and residential uses on land that had been the Fleet Industrial Supply Center. Catellus and the city executed a development agreement in June 2000 giving the company the rights to develop a residential community called Bayport and a 1.3 million-square-foot (121,000 sq m) business park. The company undertook a detailed environmental impact report, which established a mitigation program that covered all the land to which it became entitled—a program by which the company is still bound. Catellus developed the 72-acre (29 ha) Bayport community of 632 detached houses around the Ruby Bridges Elementary School and an 11-acre (4.5 ha) park.

Subject to the terms of its development agreement, Catellus assigned the residential entitlement to Warmington Homes, the Costa Mesa, California–based homebuilder that built the project. In its development agreements, the city sought to reflect the small-town character and the grid pattern of Alameda. Bayport’s blocks were typically about 200 by 500 feet (61 by 152 m) and were consistent with the varied grid pattern of the rest of the island. Catellus/Warmington achieved gross density of about nine units per acre, excluding the school and park, using lots measuring about 45 by 80 feet (14 by 24 m), comparable to lot sizes in the older community.

This site plan shows three kinds of housing: 91 two- and three-story single-family-detached houses in a neighborhood on the western portion of the property called Cadence; 106 three-story condominiums and flats called Linear, creating a more urban edge along Fifth Street across from the retail center; and 56 three-story townhouses called Symmetry on a parcel north of the Target store across Mitchell Avenue. (KTGY)

Alameda Landing

For the 146 acres (59 ha) northeast of Bayport, Catellus had hoped to create a research and development business park, but market interest was insufficient. However, there was interest for a retail center and some additional housing, which became Alameda Landing. In November 2006, the city and Catellus negotiated and executed three separate development agreement amendments: one to eliminate the company’s obligation to develop a business park; the second, to develop commercial uses on the approximately 40 acres (16 ha) east of a new two- and three-lane Fifth Street with on-street parking; and a third residential agreement for about 26 acres (11 ha) to the west, along with four acres (1.6 ha) north of Marina Village Parkway.

The agreements separated the uses to eliminate zoning uncertainty, vest development rights, and facilitate financing of both commercial and residential components. Catellus proceeded to develop a 300,000-square-foot (28,000 sq m) retail center, anchored by a ten-acre (4 ha) parcel it sold to Target for a 140,000-square-foot (13,000 sq m) store on the north end of the site, and built another 50,000-square-foot (4,600 sq m) Safeway supermarket anchor on the southern end, just north of Willie Stargell Avenue.

Seeking a more walkable center, the city encouraged Catellus to create a more urban, double-loaded retail street called Singleton Avenue through the middle of the retail area. The street encompasses four blocks on each side, about 200 feet (61 m) long with varied lot depths flanking a 50-foot-wide (15 m), two-lane right-of-way, with on-street parallel parking and 12-foot-wide (3.7 m) sidewalks, plus street trees and two through-block plazas in the center. Although those blocks are solely retail now, Alameda city planner Andrew Thomas suspects that the central, smaller-block pattern could be extended through the parking areas between Singleton and the two anchors to accommodate future mixed-use additions. An athletic club and a swim school already are quasi-retail tenants in other buildings in the center, which opened in 2015.

In return for building and dedicating the streets within the project, Catellus received a 97.5 percent credit against citywide development impact fees of $3,740 per residential unit and $4.85 per square foot ($52 per sq m) of retail space. The development agreements also required Catellus to develop and fund a transportation demand–management plan, including at buildout a maximum payment of $425,000 (2006 dollars), including up to $125,000 per year for a water shuttle to Oakland. Funding is implemented through assessments on Alameda Landing property.

Multifamily buildings were split into sizes ranging from three- to ten-plexes, forming a more urban edge along Fifth Street. Commercial spaces occupy all four corners at Singleton Avenue. A village green and a neighborhood common (at right) serve as a focal point at the inflection point of Fifth Street. (TRI Pointe Homes-Adam Hiles)

First Multifamily Units in Four Decades

Because of an Alameda city charter amendment enacted in 1973, no multifamily development had been permitted in the city. Negotiation of site-specific development agreements enabled Catellus to build the first multifamily units in nearly four decades in Alameda Landing under the city’s 2010 density bonus ordinance, which allows developers to build market-rate multifamily units if they reserve 16 percent of the units for affordable housing. A mixed-use planned development district also is available, which permits up to one unit per 2,000 square feet, which is 21 units per acre (8.5 units per ha).

To develop the residential portion of Alameda Landing to which it became entitled in 2006, allow ing up to 300 units of housing, Catellus selected the San Ramon–based northern California division of TRI Pointe Homes, part of the TRI Pointe Group of six regional homebuilders that emerged after the Great Recession and later merged with the Weyerhaeuser Real Estate homebuilding company.

To provide a more walkable center, the city encouraged the creation of a more urban, double-loaded retail street through the middle of the retail area. The street, Singleton Avenue, encompasses four blocks, about 200 feet (61 m) long, with varied lot depths flanking a two-lane right-of-way, with on-street parallel parking, wide sidewalks, and street trees. (Google Maps)

TRI Pointe Homes hired the Oakland office of KTGY Architecture + Planning to refine its concept for the project. To help integrate the residential uses with the retail center, the development team continued Singleton Avenue west through the site where it could eventually connect with another segment of Singleton Avenue along the southern edge of Coast Guard housing to the west. That segment extends to Main Street, which leads to the ferry terminal. The San Francisco Bay Ferry carries passengers on five routes between Alameda Island and San Francisco, a 20-minute ride, and across the harbor to Oakland. The ferry terminal is a 20-minute walk from Alameda Landing and less than five minutes away by rush-hour shuttle. To augment the residential/commercial connection, three-story buildings at each corner where Singleton connects with housing have commercial spaces whose design reflects the brick restaurants and retail buildings that line the opposite side of Fifth Street.

Diversity of Housing Types

To soften the impact of increased density and to appeal to the broadest housing market, the team chose to develop three kinds of housing: 91 two- and three-story single-family detached houses in a neighborhood called Cadence on the western portion of the property, placed on lots about 40 by 75 feet (12 by 23 m), slightly smaller than Bayport’s 45-by-80-foot (14 by 24 m) lots; 106 three-story condominiums and flats called Linear, creating a more urban edge along Fifth Street across from the retail center; and 56 three-story townhouses called Symmetry on a separate 4.3-acre (1.7 ha) parcel north of the Target store, across Mitchell Avenue.

Including 32 more affordable units on Alameda Landing’s southern end, that mix achieved an average density of about 11 units per gross acre (27 units per ha), not that much denser than the nine units per gross acre (22 units per ha) density of Bayport, which is consistent with the scale of the rest of Alameda.

The design divided the projects into 115 buildings (24 multifamily buildings and 91 single-family detached houses) to reduce their apparent scale. In addition, the multifamily buildings were split into six different sizes, including three-, five-, six-, seven-, nine- and ten-plexes. Even though all the 253 units were planned with two parking spaces per unit, all 506 off-street spaces are contained in individual-unit garages within each building, further reducing the projects’ apparent scale. That was intended to meet a public purpose stated in the residential development agreement to maintain the small-town character of the city. Like Bayport, 20-foot-wide (6 m) alleys provide vehicular access to houses, though in order to slow internal traffic, many do not connect directly to larger streets.

Three kinds of communal open space totaling 4.9 acres (2 ha) were incorporated into site design. A village green and a neighborhood common across from it serve as a focal point from Fifth Street toward the east. A half-acre (0.2 ha) town square serves as a private open space for neighbors but is connected through a paseo to Fifth Street. Paseos and courtyards interspersed through the four residential blocks connect them.

Private open space in the neighborhoods of single-family detached homes is concentrated between the houses, “with the great room wrapping around an exterior courtyard to allow for maximum natural light into prime living areas to take full advantage of the Bay Area moderate climate,” says Jill Williams, KTGY board chairman and principal of the Oakland office. The homes’ zero-lot design facilitates privacy for these spaces, she says. The efficiency of the site plan for the townhouses in Symmetry with adjacent walls not only increased their net density to over 19 units per acre (47 units per ha), according to Williams, but also allowed private outdoor open spaces to be larger than those for some of the single-family detached houses.

Universal Design

Incorporating universal design was an important objective of the city and the developers. The plans for two of the four single-family detached homes, accounting for 40 percent of the single-family houses, provide ground-floor suites accommodating multigenerational households or aging in place. In Linear, 22 units are fully accessible to the handicapped. They have zero door thresholds, wider doorways, housewide maneuvering clearances, removable base cabinets, and accessible controls.

To achieve more universal design, KTGY went beyond a typical three-story townhouse configuration and created overlapping units and numerous versions of interlocking units. The fully accessible ground floors of many of the houses and townhouses provide ground-floor great rooms, kitchens, bedrooms, and bathrooms that can facilitate multigenerational living. The multi-family projects come in more than ten designs, from a two-bedroom, two-bath first-floor flat to a four-bedroom townhouse.

Development Cost and Absorption

The total development cost for the three communities exceeded $75 million, says Brian Barry, vice president of project management at TRI Pointe Homes. Sale of the land closed in three phases from December 2013 to December 2015.

The 91 Cadence houses, ranging in size from 2,100 to 3,330 square feet (195 to 309 sq m) on lots averaging 2,850 square feet (265 sq m), were closed out by January 2018 at prices ranging from $1.2 million to $1.5 million; the 56 Symmetry townhouses, which vary from 1,760 to 2,300 square feet (164 to 214 sq m) for units as large as four bedrooms and three-and-a-half baths, were closed out in March 2018 at prices from $950,000 to $1 million; and 100 of the 108 Linear condominiums, which vary widely in size from 1,017 to 2,480 square feet (95 to 230 sq m), were sold at prices from about $800,000 to over $900,000 by March 2018. Homeowners association dues range from $150 to $325 per month depending on square footage.

On future projects, perhaps on waterfront projects that constitute the next phases, addition of rooftop decks and other features will be considered to enhance flexibility for younger buyers, Barry says.

The white-and-gray buildings at left are affordable housing units collectively referred to as Stargell Commons. TRI Pointe Homes agreed to donate an additional acre (0.4 ha) and capital to the city to help pay for construction of the 32 affordable units. The Alameda Housing Authority partnered with Resources for Community Development, a Berkeley, California, nonprofit that developed the $17.4 million project. It contains one- to three-bedroom units that are rented to qualified tenants earning 30 to 60 percent of AMI. (TRI Pointe Homes-Adam Hiles)

Affordable Housing

To meet the 16 percent inclusionary zoning provisions in Alameda, 16 affordably priced, deed-restricted homes were included in the projects, Barry says. Those units can only be resold to buyers with incomes that do not exceed 80 percent of the area median income (AMI) at the time of resale. TRI Pointe Homes also agreed to donate an additional acre and capital to the city to help pay for construction of another 32 affordable units.

In addition, the Alameda Housing Authority partnered with Resources for Community Development, a Berkeley nonprofit organization that developed a $17.4 million apartment project called Stargell Commons, which has one- to three-bedroom units that are rented to qualified tenants earning 30 to 60 percent of AMI, which in 2016 was $93,600 for a family of four. When the development opened in 2017, rents ranged from $491 for a one-bedroom unit to $1,437 for three bedrooms. The East Bay Times reported that more than 11,700 people applied for the 32 units upon opening.

The master-plan stage for the north waterfront contains mixed-use retail, office, and residential projects. As the two-decade planning process has evolved, the city has become more urban in its objectives, seeking more vertical mixed uses. The plan allows for up to 400 housing units as well as 364,000 square feet (33,800 sq m) of maritime commercial space within the existing industrial buildings and at least 5,000 square feet (465 sq m) of retail, restaurant, and other visitor-serving uses. (City of Alameda)

Planning Becomes More Urban

The city is still at the master planning stage for the northern waterfront mixed-use retail, office, and residential projects, Thomas says. As the two-decade planning process has evolved, the city has become more urban in its objectives, seeking more vertical mixed uses. The plan allows for up to 400 housing units as well as 364,000 square feet (33,800 sq m) of maritime commercial space within the existing industrial buildings, plus at least 5,000 square feet (465 sq m) of retail, restaurant, and other visitor-serving uses. Greater density may be granted in proportion with the increase in trips accommodated through the transportation demand–management program.

To encourage vertical mixed uses in the area, the master plan allows buildings with ground-floor retail space to exceed five stories. To ensure construction of smaller units affordable to people with a moderate income, at least 10 percent of market-rate units must be no more than 1,200 square feet (111 sq m). Parking spaces for residential units may not exceed two per unit. At least 15 percent of housing units must include universal design features.

And in a reversal of its four-decade multifamily exclusion, no more than 30 percent of units on the waterfront may be single-family homes. At least 15 percent of all the units must be affordable, with deed restrictions enduring for at least 59 years. The city also has a right of first refusal on resales.

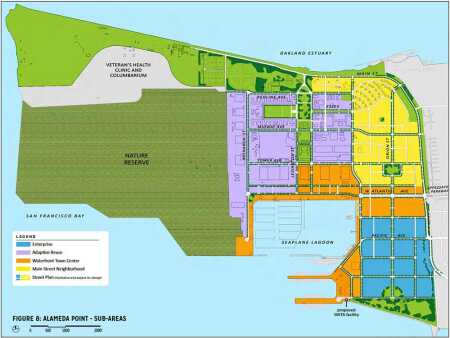

Click to zoom. Over 556 acres (225 ha) of land remains to be redeveloped on Alameda Point west of Main Street. The city has divided that land into four subareas: a waterfront town center neighborhood surrounding the southern seaplane lagoon; a Main Street neighborhood for a mixture of housing types with supportive services; an adaptive use subarea that contains over 2 million square feet (186,000 sq m) of existing buildings; and an enterprise subarea for research, industrial, and office development. (City of Alameda)

Planning Alameda Point Development

Over 556 acres (225 ha) remain to be redeveloped on Alameda Point west of Main Street, where the city has dealt with a variety of setbacks, including unfulfilled agreements with a consortium of master developers, the Great Recession, developer withdrawals, and the 2009 defeat of Ballot Measure B, which would have approved a 300-page agreement with Irvine-based SunCal to develop the site; 85 percent of the voters opposed the measure on fears of traffic paralysis to and from an island connected to the mainland by only four bridges. It is on these western sites where a third consortium of developers is in negotiations to redevelop the first 68 acres (28 ha) of western Alameda Point. The city has divided the western land into four subareas:- A 125-acre (51 ha) waterfront town center neighborhood surrounding the southern seaplane lagoon for a mixture of retail, residential, and office uses.- A 108-acre (44 ha) main street neighborhood for a mixture of housing types with supportive services.- A 216-acre (87 ha) adaptive use subarea containing over 2 million square feet (186,000 sq m) of existing buildings, including the “big whites”—22 interlinked two-story office buildings, one of which is City Hall West. Their location across a one-acre (0.4 ha) green perpendicular to another green and street couplet makes them appropriate for institutional and office uses. Other buildings in that subarea are adaptable for light manufacturing, distilleries, and other food-related businesses.- A 107-acre (43 ha) enterprise subarea for research, industrial, and office development.

In addition, just west of Alameda Landing and east of Main Street, the Coast Guard maintains for its service members 241 World War II–era, low-density two-, three-, and four-bedroom townhouses on about 50 acres (20 ha) that may be redeveloped.

Despite the gift of land, the varied requirements of public and private partners needed to undertake redevelopment can lead to extended negotiation and performance periods during which market conditions, development costs, public opposition, and planning practices can and do change. Alameda Landing demonstrates that it is possible to overcome such obstacles by planning with flexibility.

WILLIAM P. MACHT is a professor of urban planning and development at the Center for Real Estate at Portland State University in Oregon and a development consultant.