When it opened more than 100 years ago, Lorton Reformatory in northern Virginia was anything but an ordinary prison.

President Theodore Roosevelt, who commissioned the novel correctional facility in response to the deplorable conditions found in the Washington, D.C., penitentiary system, envisioned a place that featured a light-filled, open-air, minimally secure design where inmates could be rehabilitated through work.

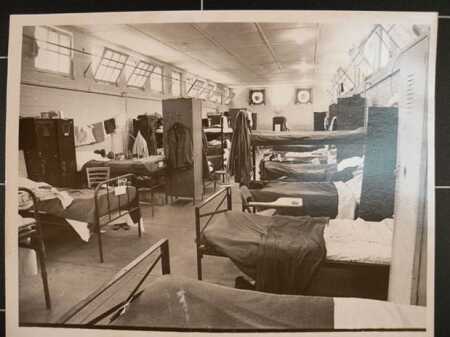

Built in the 1920s by bricks formed by the hands of prisoners at the nearby Workhouse kiln, the reformatory, with its colonial revival architecture, contained gabled dormitories instead of cellblocks that faced a grassy central courtyard, making it look more like a university campus than a bastion of punishment. It served as a model for the Progressive Era’s take on corrections.

ULI Washington: Case Study: Liberty in Lorton on October 14

So, it was only fitting that when it came time to adapt and reuse the historic property after the prison closed, it also required creativity and an outside-the-box approach to its construction techniques.

Now, the repurposed reformatory site is blossoming into a vibrant urban community that when completed will feature 165 apartments, 157 townhouses, 24 single-family homes, and up to 100,000 square feet (9,300 sq m) of office and retail space—a $190 million development known as Liberty.

Much has changed since the prison’s inception. As the Progressive movement’s philosophies faded away, the reformatory increasingly took on more serious offenders, leading to the addition of higher-security facilities. Ironically, some of the same concerns that led to Roosevelt’s commissioning of the prison in 1908, such as overcrowding and violence, led to Lorton’s closure in 2001, according to congressional testimony. Fairfax County purchased the 2,300 acres (931 ha), renamed Laurel Hill after the home of Revolutionary War soldier Major William Lindsay located there, from the D.C. Department of Corrections for $4.2 million in 2002. It included not only the reformatory but also the Workhouse and agricultural land. In the years since, the majority of the site has been redeveloped into a master-planned community that includes housing, recreation, a landfill, a golf course, schools and the Workhouse Arts Center.

“This Laurel Hill piece was the last 80 acres [32 ha],” says Heather Diez, project coordinator for the Fairfax County Office of Public/Private Partnerships.

The D.C. Workhouse and Reformatory sites entered the National Register of Historic Places in 2006, ensuring the integrity of the historic structures needed to be maintained. So, Fairfax County sought a master planner for the reformatory with experience in adaptive use, who could link residents with services in the fairly rural southern part of the county that, if successful, would continue on as the master developer, Diez says.

In 2008, the Alexander Company, based in Madison, Wisconsin, was hired to complete the master plan. Alexander had recently redeveloped the National Park Seminary in Silver Spring, Maryland, and followed a similar formula for the Liberty project, says Dave Vos, development project manager for the Alexander Company.

“We are a development company who does our own planning, and we have the ability to bring in development partners and consultants to test the market for various uses to make sure that there’s a market for them,” Vos says.

He says they evaluate how to eliminate any financial gaps in those proposed uses with funding sources that Alexander specializes in securing, including historic tax credits, which was something that also appealed to Fairfax County.

“It was important to find somebody . . . who had that skill to pursue and obtain historic tax credits, which were used to finance a lot of this project,” Diez says. The master planner/developer also needed to establish relationships with the Virginia Housing Development Authority (VHDA) and the Virginia Department of Historic Resources to effectively navigate the approval process.

In the master plan, Alexander described their vision as a “hub of community spaces” that would connect residents to work, retail, and recreation through auto, pedestrian, and cycling transportation. The former prison dormitories would be converted into a mix of market-rate and affordable apartments complete with high-end urban finishes of exposed brick, maple cabinetry, and granite countertops, with amenities including a pool, a fitness center, and a community room. The penitentiary would be transformed into commercial or residential space. At the site of a previous ballfield where Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, and Louis Armstrong once entertained inmates, a community green would invite residents to relax over a picnic or during a family movie night. New housing, including both townhouses and single-family homes, would be constructed along tree-lined streets. Shops servicing the neighborhood were designed to include a market, a bank, a pharmacy, restaurants, and more.

After meeting extensively with the community, which Diez says embraced the project, the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors approved the master plan in 2010, and Alexander moved on with the interim development agreement. Though the economic downturn did not have much impact on the overall plan, Vos says the Alexander Company did have one area of concern.

“The for-sale housing became a concern as we were finalizing our development agreement with the county, because that was right after the backside of the recession,” he says.

Vos says Alexander sought a development partner willing to commit to that part of the equation, so the company turned to Elm Street Development, based in McLean, Virginia.

“Bringing in Elm Street was very helpful, because they’re a very experienced land developer in that region,” Vos says.

Each team member now had a defined responsibility and area of expertise.

“Elm Street’s role was basically all the infrastructure construction for all of Phase I,” says Jim Perry, regional partner and vice president at Elm Street, with William A. Hazel, based in Chantilly, Virginia, serving as their general contractor for sitework. “Then we also developed the first phase of market-rate housing, which is 107 units.”

Alexander would handle the interiors and exteriors of the historic buildings, with Baltimore’s Southway Builders serving as their general contractor and with Van Metre Homes of Stone Ridge, Virginia, building the new construction housing. Fairfax County would contribute a capped amount of $12.8 million entirely toward infrastructure.

Planning to Succeed

With the partners in place, they started negotiating the final agreement and securing financing. This took longer than expected, due to some challenges that arose.

In 2012, a ruling by the Third U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in the Atlantic City Historic Boardwalk Hall case jeopardized their tax credit financing. The court decided that investors need to have a significant stake in a development in order to receive historic tax credits. Because of this, tax credit investors pulled out of the market as they waited for clarification from the Internal Revenue Service. Vos says that Alexander and others lobbied for the Treasury Department to provide guidance as to what level of investment qualified for the credits, which was finally issued in 2014.

With that resolved, the final hurdle was created by Fairfax County’s plans to retain ownership of the historic structures on a 99-year ground lease. “That ground lease did create some problems for us because we were financing a portion of our project through bonds that were issued by the Virginia Housing Development Authority,” Vos says.

Both the VHDA and the county wanted to be able to control insurance proceeds in the event a casualty occurred to the historic structures. The county wanted to ensure that proceeds were used to repair or replace the historic buildings, while the VHDA wanted the ability to use the proceeds in a manner that ensured the continued financial viability of the project.

“It took us the better part of the year to work through that negotiation between the state and the county to come up with a compromise that protected each party’s interests and allowed us to proceed,” Vos says. “Without those two setbacks, this project probably would’ve started about three years prior.”

Both the county and Alexander pulled from their previous public/private partnerships to structure this one for the best chance of success. Diez says the county had learned to require that the adaptive use portion be completed before the new residential could be built. And based on Alexander’s experience, the developer partners did not move forward until they were all ready to close their financing, so everything was executed on the same day, which Vos highly recommends.

“If you can avoid having the final development agreement signed until you are actually ready to close, that takes a whole part of the equation away because you know you have the financing in place to do it and there don’t have to be as many ‘what-ifs’ in the agreement,” he says.

When complete, the $190 million Liberty development will feature 165 apartments, as well as townhouses and single-family residences. Residents of Liberty can connect with their neighbors at the community green or other amenities, and the development will also include up to 100,000 square feet (9,300 sq m) of office and retail space. (The Alexander Company)

Turning a Scheduling Nightmare into Dream Results

With closing complete, the partners were ready to get on site—all at the exact same time, which is not the typical delivery method.

“Normally, you’d want to get all your sitework done or substantially done before you start your vertical construction, and in this case much of the vertical construction was there,” Vos says. “Elm Street was required to put in sanitary/sewers that were up to 20 feet [6 m] deep and that were as close as ten feet [3 m] away from buildings that we’re supposed to be reroofing, tuckpointing, and repairing windows on.”

But Elm Street was prepared.

Knowing the partners would need to work together under tight conditions, and that earthwork on the previously manipulated site had the potential to create delays and significant change orders, Elm Street says they realized early on that they would need assistance with scheduling and management. So they brought in SmartSite, a construction management firm based in Waldorf, Maryland.

“We had used SmartSite on other sites previously with good success,” Perry says. “The larger and more complex a project is, the more benefit they add. Since this project was big and very challenging, it was a natural site to bring them in on.”

When SmartSite joined the team in 2013, managing partner Frank Duduk said they quickly recognized that this was unlike any project they had worked on in the past, even for a firm experienced in solving complicated problems.

“When we first got involved with the project, it was pretty overwhelming, as you can imagine,” Duduk says. “There’s just so many moving parts.”

Duduk says Liberty reflects the trends in urban residential development, with increased density and mixed uses, where the best way to develop the land is to bring together several interdisciplinary partners that each offer a key area of expertise. That is where SmartSite adds value, by getting all partners on the same page through technology, data, and modeling, he says. But Liberty required coordination on a whole new level.

“This was without a doubt the most complicated schedule we had ever had to develop, because everybody wants to get paid and recover their investment as early as possible,” Duduk says. “Here we are, three years before we’re going to break ground, and we’ve got to start promising them which buildings are going to be done when.”

With the way the development agreement was structured, SmartSite had to create a schedule with the partners starting on the same day and, ideally, finishing on the same day.

“That, for a construction manager, is a worst-case scenario,” Duduk says.

The other major goal was to keep earthwork and demolition out of the critical path, which was not going to be easy with the adaptive use occurring simultaneously.

SmartSite set out to identify the project timeline and complete an early building information modeling (BIM) sketch of what issues may occur during construction. The company’s approach to this is different because SmartSite takes the engineering plans, which are primarily designed for permit approval showing existing and future grades, and creates an interim condition model, which shows what would actually need to happen in order to build so that there are no disagreements between the stakeholders. This has traditionally been an area of conflict in development, particularly complex ones, because it is usually overlooked in the permitting process, Duduk says.

Flying through Construction

One of the emerging ways that SmartSite collects its data is through drone use—and that collection is happening far sooner than it traditionally has in development.

“The difference with what we’re doing is we’re inserting that into the design, budgeting, and implementation phases for the owners instead of the normal workflow, which is you hire a bunch of contractors, then they hire a bunch of 3-D modelers, and then they come back to the owner and say your plans don’t work,” Duduk says.

The drones provide not only a visual map of site changes through detailed imagery, but also changes in contour, digital volume, and stockpiles.

“Now I can fly a drone and create a progress surface and compare that to the interim grade surface to determine how close the contractor is to where they need to be and how much work they’ve gotten done and how much work they have left,” Duduk says.

The interim condition model creates the quantities, production units, and schedules, linking time, money, construction, as-builts, and design in value-engineering. Duduk says in the past, developers let the field worry about that level of data, which is why change-order percentages on earthwork can be so substantial. He believes that SmartSite’s delivery approach will become the future standard for development.

“I think we’re very much at the head of the line when it comes to establishing a new best management practice,” he says. “It’s really hard to believe that everybody doesn’t do it this way.”

Perry says the data-driven schedule, published before work began, and extensive modeling from SmartSite were a tremendous asset. It also helped them negotiate resource commitments from site contractor William A. Hazel at the outset. They were able to know how many crews they needed where and when to keep everything on track. Doug Palatt, project manager for William A. Hazel, says that transparency in communication also was important.

“The project team planned, managed, and implemented the schedule with weekly updates to ensure the critical path was maintained,” Palatt says. “Having all parties involved in this process was instrumental in the successful progress of the project.”

Because of SmartSite’s services, Perry says they were able to peacefully coexist and operate even with the building crews working on 34 structures spread out over 50 acres (20 ha), according to Scott Carver, Southway director for Washington, D.C., and northern Virginia, who says they learned not to underestimate the manpower needed and ended up with a large staff devoted to Liberty.

“We would not have been able to get it done within the time frame we did without that kind of assistance from [SmartSite],” Perry says.

Another area where SmartSite added benefits was with the modeling of dirt operations, he says. The geotechnical investigational report revealed a high level of risk for earthwork, due to existing fills. It indicated that material needed to leave the site and that deep dynamic compaction would be required—a dangerous proposition with the proximity to the historic buildings. So SmartSite performed extensive field investigation and analysis.

They found that some of the material was much better than the initial borings had suggested, allowing them to recast the dirt numbers and find places where material could be reused instead of removed.

“The way they create these 3-D models, you get a level of analysis that is just not available otherwise, that allows you to make decisions very quickly about how to save money and grab the stuff that’s in front of you,” Perry says.

SmartSite applied the same level of analysis to other areas, which led to reordering the construction of a retention pond and sanitary lines.

“Rewriting the sequence isn’t so hard if you have the data that we have,” Duduk says. “Our approach is to really simply try to model three dimensions of the problem so that . . . you’re squeezing as much guesswork out of it as possible.”

Though they started the project with $2 million in early risk assessment, Duduk says that, with SmartSite’s methods, the risk was basically down to zero by the end.

“It’s the worst possible operational and delivery nightmare with the best possible on-time, under-budget completion,” he says.

Moving In and Moving On

The converted prison is now welcoming its new residents, and Fairfax County is excited for the community’s future.

“This has just been a really well-embraced project,” Diez says. “I haven’t seen one go this smoothly. We’re fortunate we got such great partners.”

They are looking ahead to Phase II, which will develop the maximum-security penitentiary into residential, commercial, retail, and office space. Work is expected to begin in 2018, taking about 18 months to complete.

The Liberty development partners have worked together so successfully that they have teamed up again to submit a proposal for another Fairfax County public/private partnership, to adapt and reuse the Mount Vernon School. The county hopes to be under contract there in early 2018, Diez says, and they’re planning to use the lessons learned from Liberty—that when developing a modern urban community, it’s not just about filling square footage, but also making sure the components of the site service each other. She says the county is looking forward to continuing to enhance the quality of life for its residents with projects such as Liberty.

“We greatly enjoy being involved in something like this that goes so successfully,” Diez says. “To be able to find the right partner and turn it into something unique and just a benefit to the community is something we were seeking, and I think it’s definitely something that we’re achieving.”

Karen M. Scally is a freelance writer with construction media experience. She is located in the Detroit metropolitan area and can be reached at [email protected].