As single-use suburban office parks across the nation suffer increasing vacancies, developers have begun to acquire and transform them into mixed-use centers. Meanwhile, as corporations as different as Weyerhaeuser and General Electric gravitate from office parks to center cities like Seattle and Boston, respectively, office park redevelopers increasingly seek to create walkable urbanism with diverse uses within multitenant, mixed-use, nascent downtowns. In south Florida, a father/daughter development team took on the task of developing an entire new downtown out of what had been an office park.

Initially developed in the 1970s by Jacksonville developer Ira Koger, the 120-acre (48.5 ha) Miami Koger Center office park (later renamed Doral Center) in Doral, Florida, had accumulated 32 buildings with about 1.5 million square feet (140,000 sq m) of office space when it was sold to that father/daughter team, operating as Coral Gables–based Codina Partners, through a 2004 acquisition agreement.

Until it was incorporated as a separate city in 2003, Doral had been an unincorporated area of Miami-Dade County just west of the Miami International Airport, about ten miles (16 km) from downtown Miami. Its name is the compound of the first names of its initial New York developers, Doris and Alfred Kaskel, who acquired 2,400 acres (971 ha) of swampland for only $49,000 in 1959, then developed the Doral Hotel and Country Club there in 1962.

The office park is immediately east of that club, now called Trump National Doral Miami, an 800-acre (324 ha) resort with five 18-hole golf courses, 700 hotel rooms, conference space, and a 50,000-square-foot (4,700 sq m) spa. The resort also houses the Pritikin Longevity Center and multiple restaurants and shops.

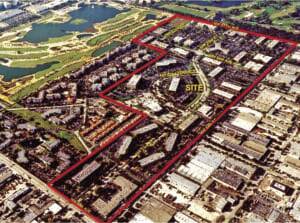

Codina Partners bought the 120-acre (48.5 ha) office park through serial purchases starting in 2006. It stretches east about 4,000 feet (1,200 m) from Trump National across NW 87th Avenue to NW 79th Avenue and about 2,000 feet (610 m) south from NW 54th Street to NW 51st Street. The acquisition agreement contained a series of rolling options to take down parcels within the property.

Ana-Marie Codina Barlick, chief executive officer of Codina Partners, a partnership with her father, prominent south Florida developer Armando Codina, says the price was based on the raw value of the land because the company’s intention from the beginning was to demolish all but four of the buildings as it built the project, named Downtown Doral. While the cost of demolition was to be borne by the sellers—investment groups managed by J.P. Morgan Chase—Codina Partners worked closely with them to maintain cash flow to the sellers until the parcels were needed for redevelopment.

The timing of the purchase—2004, a year after incorporation of the city and seven years before the Trump Organization’s $350 million investment at Trump National—was auspicious. Also, with more than 30 years of experience and Armando Codina’s previous role as chairman of Flagler Development, the development company founded by pioneering Florida railroad and development magnate Henry Flagler, the developers had the reputation needed to make credible the idea of transforming an office park into a downtown.

In 2005, Codina Partners hired Miami-based new urbanist planners Duany Plater-Zyberk (DPZ) to develop a site plan and proposal for a mixed-use planned unit development (PUD) for a program that includes more than 1 million square feet (93,000 sq m) of office space; a main street with 180,000 square feet (17,000 sq m) of retail and restaurant space; 2,840 condominiums, townhouses, and apartments; a new 60,000-square-foot (5,600 sq m) city hall; a three-acre (1.2 ha) park; and a K-5 charter school.

The scale and block size of the plan were determined by the existing infrastructure and by the program for higher-density high-rise towers, both of which led to larger block patterns, says Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, partner in DPZ. The DPZ plan remains essentially intact, Codina Barlick says, though she notes that her firm used several architects over the years in order for “the downtown to be authentic, organic, and not feel like a project.” Within the density constraints of the PUD is the flexibility to adjust to market demand, she notes. The overall residential density was based on 25 units per acre (62 units per ha) for the 120-acre (48.5 ha) site.

The plan preserved 25 acres (10 ha) at the center of the site, where four of the newest three-to-five-story office buildings were located; those structures, built in the 1990s, contain 369,000 square feet (34,300 sq m) of office space. The buildings, configured in a random pattern that does not align with the rectilinear grid of the balance of the site, are interspersed with curvilinear surface parking lots. This portion of the site constitutes 20 percent of the initial site; gross rents from the buildings represent about $10 million per year, which the developers wanted to retain during the multiyear buildout of the downtown development. In addition, that area represents a land bank of redevelopable property that generates cash flow during a longer holding period; Codina Barlick says her firm has no plans to redevelop those properties, but added that could change as the downtown reaches buildout.

The balance of the site on the north and west sides contained the other 28 buildings—mostly one- and two-story structures inexpensively constructed in the 1970s to house government workers. They totaled more than 1 million square feet (93,000 sq m) of Class C office space and were marked for demolition and redevelopment. Careful planning around lease terminations helped the developer avoid the added expense of lease buyouts. Codina Barlick says the Great Recession actually assisted in that effort because some tenants chose to downsize in smaller quarters in remaining buildings.

One of the earlier projects developed in Downtown Doral was the 60,000-square-foot (5,600 sq m) new City Hall, built on two acres (0.8 ha) in the north-central portion of the site. The city selected Codina to construct the building and a 250-space garage behind it. Codina sold the parcel at a discounted price of $1.3 million to the city and delivered a turnkey building. The city financed the project’s $20 million development and construction cost.

At City Hall’s southeastern corner, a three-story rotunda capped by a cupola marks the new civic downtown center. Immediately to its south, Codina Partners created a city park on three acres (1.2 ha) of land it donated to the city in exchange for impact-fee credits. The partners spent $1 million creating the park and an additional $1 million on Micco, a large shade sculpture by artist Michele Oka Doner. A traffic circle between City Hall and the park visually connects the two, creating a civic heart for Doral. A circular brick plaza and an oval walkway add to its civic character.

Just south of the park, Codina Partners provided for the Downtown Doral Charter School, which accommodates up to 768 students from kindergarten through fifth grade plus a private preschool for up to 80 students. The partners donated the 3.5-acre (1.4 ha) site to the Miami-Dade County Public Schools (MDCPS) in lieu of school impact fees that would have been charged to the downtown development. The school system ground-leases the site to Downtown Doral Charter Elementary School (DDCES), a 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation of which Codina Barlick is president and which is responsible for operating and maintaining the school.

The nonprofit corporation hired MDCPS to design and build the 72,000-square-foot (6,700 sq m) school building, and the Florida Development Finance Corporation (FDFC) issued $21.8 million in ten-, 20-, and 30-year serial bonds to finance the project, debt service reserve, and the initial 32-year, $4.5 million capitalized ground lease rent, which FDFC loaned to the DDCES. The bonds will be repaid out of the school’s operating budget, which is funded by the state.

The mission of the tuition-free charter school is to provide a multilingual education to students in English and either Spanish or Portuguese. Under state statutes governing charter schools, nearby residents of Downtown Doral get preference for admittance to the school for up to half of the school’s enrollment. As a result, disproportionate numbers of new residents, many of whom recently immigrated from Venezuela or Brazil, have sought apartments in Downtown Doral. The developers are including more three-bedroom units in residential buildings as the project proceeds in an effort to attract more families, Codina Barlick says.

To the east of City Hall, Codina Partners developed 8333 NW 53rd St, a 150,000-square-foot (14,000 sq m) office building with a rotunda at its southwestern corner and its own six-level, 700-space parking garage. Between City Hall and the new office building, a two-acre (0.8 ha) site is planned for another office building and parking structure. The local office market still demands a parking ratio of four spaces per 1,000 square feet (93 sq m) of office area, Codina Barlick says.

South of the park, NW 53rd Street curves to become Main Street, a two-block-long central thoroughfare of Downtown Doral running east–west to intersect with NW 87th Avenue and across to a traffic circle within Trump National. Main Street offers retail spaces along both sides of the street, and retail space also runs along the perpendicular NW 87th Avenue, a major commercial street. An existing traffic light at NW 87th and Main Street led planners to select that east–west corridor as the site’s retail axis.

The 1,000-foot-long (300 m) Main Street divides the main downtown area into two superblocks of about 12 acres (4.9 ha) each. A north–south street, Paseo Doral, divides the superblocks with two linear urban courtyards—long, narrow parks surrounded by buildings—flanked by one-way streets lined with parallel parking. A symmetrical development plan locates six high-rise residential towers placed to preserve views and preclude shadows, Plater-Zyberk says.

The first two 20-story towers, 5252 Paseo and 5300 Paseo, are in final development. The first tower, with 203 units, sold out at prices averaging $375 per square foot ($4,166 per sq m) for units ranging from $300,000 to $800,000. All the units sold within 90 days. Sieger Suarez Architects of Miami designed the towers. The second tower has 219 units and recently was 75 percent sold at prices averaging $400 per square foot ($4,444 per sq m).

Lennar Commercial, the commercial arm of the Miami-based housing developer, is Codina’s partner in developing the Main Street retail area, made up of single-level retail space lining parking and the residential towers. The retail area is intended to total about 200,000 square feet (18,600 sq m), with at least 20 restaurants and shops. Half of the 80,000-square-foot (7,400 sq m) Phase I will be restaurants, Codina Barlick says. Each portion of the superblock will have 200 parking spaces in a two-level parking structure at its center. Another 50 spaces are in linear surface parking lots lining NW 87th Avenue. The restaurants at the corners of Main Street range in size from 5,000 to 6,000 square feet (460 to 560 sq m). Another 40,000 square feet (3,700 sq m) of retail space will be included in Phase II.

All ground-level and on-street parking is free to users, although the developers might welcome city meters for the on-street spaces as a way to allocate parking use, Codina Barlick says. Above the retail parking spaces, another level of parking will be sold to condominium buyers at $20,000 per space.

A 50,000-square-foot (4,600 sq m) Publix supermarket is planned for NW 53rd Terrace at the end of Paseo and across from Downtown Doral’s public park. The store will be in a large urban format and specialize in prepared foods. With construction to start this September, the Publix is scheduled to open in December 2017. Other current service tenants are a salon, a bank, a wine and spirits store, and a dry cleaner.

On six acres (2.4 ha) on the southwest corner of the site, the developers built 85 townhouses designed by Raul Sotolongo, principal of Sotolongo Salman Henderson Architects, based in Doral. The 24-foot-wide (7 m) units are designed as Mediterranean-style villas with white stucco walls, red tile roofs, covered balconies, and arcade entries. The three- to four-bedroom units range from 1,800 to nearly 2,000 square feet (167 to 186 sq m) and have garages. Prices range from $600,000 to over $1 million. Codina developed the townhouses through a partnership called CC Devco Homes, a Codina-Carr Company.

On two five-acre (2-ha) sites flanking NW 53rd Street near the northeast entrance to the site are twin apartment complexes, Cordoba I with 224 units and Cordoba II with 232. The one-, two-, and three-bedroom apartments range in size from 700 to 1,300 square feet (65 to 120 sq m) and rent for $1,500 to more than $3,200 per month. Parking within the complex was planned at an average 1.3 spaces per unit. Codina Partners and J.P. Morgan completed both phases of Cordoba in 2013, and institutional investors now own the properties.

Most of the infrastructure for the overall project was built over the past three years, Codina Barlick says. It was partially self-financed by Codina Partners and a loan from Goldman Sachs. The infrastructure expenditure will be repaid through a special-purpose community development district (CDD), which is authorized to issue tax-exempt bonds to pay for construction of infrastructure improvements. Developers pay taxes and assessments to cover the debt service on those bonds.

The development plan is currently being more than doubled to 250 acres (100 ha). This April, Codina and Lennar finalized an agreement to buy the 130-acre (53 ha) Doral Great White Golf Course, one of the five operated by Trump National, from the Singapore-based private, limited-investor entity GIC Pte. Ltd. for $96 million.

The golf course adjoins the Downtown Doral property, and 66 acres (27 ha) are currently entitled for development of as many as 2,709 residences, including condominiums, apartments, townhouses, and single-family homes. Entitlements also would allow more than 800,000 square feet (74,000 sq m) of office space and as much as 300,000 square feet (28,000 sq m) of retail space. Codina Partners and Lennar will each develop portions of the golf course for a mixture of uses weighted to a slightly lower residential density, Codina Barlick says.

Transforming a suburban office park into a downtown can be challenging. Unanticipated disasters like the Great Recession, which caused serious harm to the Florida market, led to extensive delays. But opportunities not originally envisioned also arose, such as the ability to acquire the Great White Golf Course and more than double the project’s size.

The city now has more than 50,000 inhabitants and a median household income topping $70,000. Headquarters operations for Carnival Cruise Lines, Univision, and Perry Ellis, plus the regional operations of major companies, provide thousands of jobs.

Codina’s success building Downtown Doral has attracted other developers to the area. Just south of the Great White Golf Course, the Related Companies is developing CityPlace Doral, an $800 million mixed-use project designed by Miami-based Arquitectonica, which will bring to a main street 250,000 square feet (23,000 sq m) of lifestyle retail space with 30 bars and restaurants, topped by 1,000 apartments and condominiums. The development will include a Fresh Market (an upscale southeastern food market chain), a Kings bowling alley, and a CinéBistro Cobb movie theater with in-theater dining. Downtown Doral was developed to be family oriented, says Codina Barlick, and she thinks that CityPlace Doral’s emphasis on regional entertainment will be a complementary project.

Traditional downtowns were developed over long periods of time, incrementally undertaken by a variety of developers. What was atypical in the last half of the 20th century was the wholesale removal of large office users from traditional downtowns and their relocation into single-use office parks in the suburbs. Now that the millennial generation resists working in single-use environments, the transformation of those environments into new mixed-use centers and downtowns by single developers is also unusual. Downtown Doral shows one way to go about it. UL

William P. Macht is a professor of urban planning and development at the Center for Real Estate at Portland State University in Oregon and a development consultant. (Comments about projects profiled in this column, as well as proposals for future profiles, should be directed to the author at [email protected].)