The mental and physical benefits of being close to bodies of water—or “blue space”—have made headlines amid growing consumer interest in health and wellness. Scientific studies have shown the positive impacts of living and spending time near oceans, lakes, ponds, and rivers—benefits including reduced stress and anxiety, improved sleep, and generally a healthier and more active lifestyle. A population-based study published in Scientific Reports examined the effect of urban waterways on mental health and found that proximity to water showed benefits for quality of life.

In the United States, a 2022 report by home warranty company American Home Shield found that a waterfront view increases the value of a property by an average of 78.1 percent.

For some people, the desire to reside close to water may be physiological, whereas for others, it’s simply a geographical choice—location, location, location. In such cities as Chicago and Minneapolis, for example, high-rise multifamily residences on the Chicago and Mississippi rivers, respectively, tend to be near employment, entertainment, and recreation options. With them often comes a willingness to pay a lofty price for a condo or rental apartment. In turn, developers have focused predominantly on building market-rate or luxury properties geared to the highest earners. This tendency makes fiscal sense, as there’s only a finite amount of riverfront land available, and such properties tend to hold their value and appreciate over time.

It’s challenging to find prime riverfront land in major U.S. metros to house new market-rate properties, let alone for an entirely affordable or mixed-income community, but the importance of promoting equitable riverfronts can’t be overstated. Are cities and developers doing enough to open these premier locations to all socioeconomic levels?

What makes a riverfront equitable?

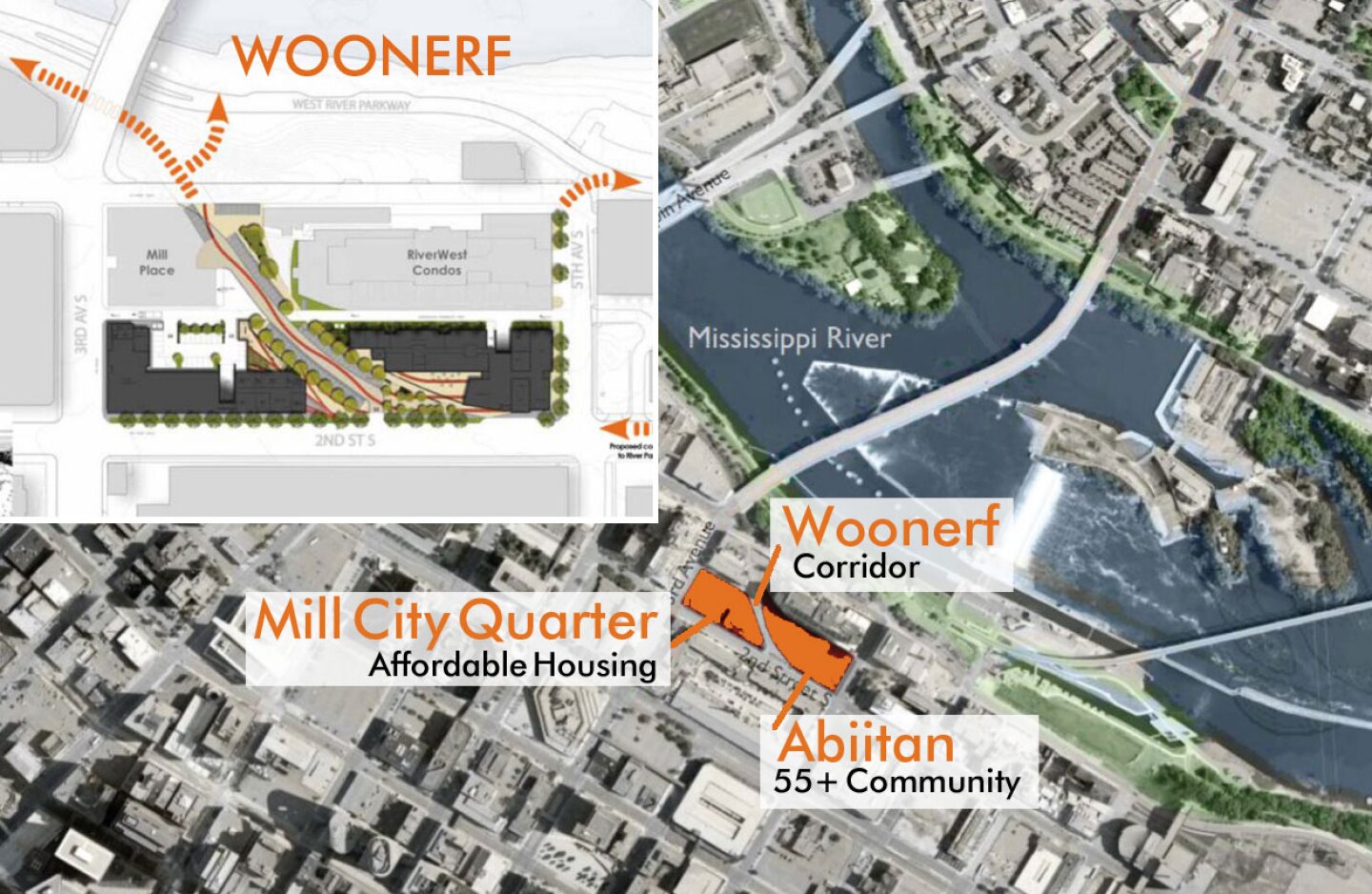

BKV Group utilized ‘inclusionary zoning policies’ for Mill City Quarter in Minneapolis along the Mississippi River, an affordable 150-unit apartment building—along with a separate 55+ property dedicated to senior independent, assisted and memory care—located adjacent to a pedestrian-friendly woonerf that directly connects to the waterfront just a half-block away.

BKV Group

Historically, riverfronts were turned over to industry and commerce, leading to widespread pollution of urban waterways and the land that surrounds them. After de-industrialization, many cities reclaimed their riverfronts, thus sparking a mix of public and private investment that drove up land prices in subsequent years. Fundamentally, the riverfront is no different from any other area of a city where economic diversity is essential to creating a thriving community.

Although we lack a textbook definition for equitable riverfronts, I point to two clear delineators: the onsite development has an affordable housing component or is entirely affordable, or the surrounding lands are fully open and accessible for public use. Some major cities, including Minneapolis, have inclusionary zoning policies to help ensure that neighborhoods, especially ones around such prime real estate as the downtown riverfront, remain diverse and equitable.

Our firm, BKV Group, applied this policy in the architectural design of Mill City Quarter, along the Mississippi River. The community adjoins an affordable 150-unit apartment building—along with a separate 55-p[us property dedicated to senior independent living, assisted living, and memory care—on either side of a pedestrian-friendly woonerf, which was once a rail corridor, that directly connects to the waterfront, just a half-block away. The mixed-use complex, which also includes 15,000 square feet (1,393 sq m) of retail space, transformed two large city-owned parking lots in the Mill District, one of Minneapolis’ most popular neighborhoods.

The other aspect of making a riverfront equitable is the creation of public spaces available for everyone’s use, such as riverwalks, parks, and other amenities. BKV was involved in the recently completed Mississippi Crossings improvement project for the city of Champlin, a far-north suburb of Minneapolis, where we transformed 160 acres (64.75 ha) of riverfront land, adding a pavilion, 600-person open-air amphitheater, playground, recreation area, and boat landing.

Champlin officials had been working for more than a decade to bring much-needed recreational activities to the community. The city collaborated with BKV and Greco Properties through a public-private partnership to secure funds for the project and design it within the allowances of various agencies and regulation guidelines for riverfront development.

Getting resourceful

Some creativity is needed to bring more equity to our riverfronts, but it will take a mix of public and private financing in the form of grants, incentive programs and other subsidies, and land availability. City-driven identification of opportunity zones is one place to start, because these typically distressed, up-and-coming areas offer tax incentives in exchange for investment.

Additionally, real estate brokers will have to be savvy and visionary enough to identify land plots that may not, at first glance, appear development-worthy, such as ones with utilities passing through them, including sites with existing structures and infrastructure that must be incorporated, improved, or removed entirely.

In finding innovative ways to get past these obstacles, we can create new opportunities for more equitable development. BKV, in partnership with Dominium Development, was able to do just that with Upper Post Flats, located on the historic Fort Snelling site, at the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers in the Twin Cities.

The 192-unit affordable housing development is an adaptive use of former military housing. With its legacy as military housing going as far back as the Spanish-American War, the new community will house many veterans and their families. Because of the historic significance of the site, Upper Post Flats received tax credits that contributed to the feasibility of making it an all-affordable development.

Pillsbury A-Mill is an iconic Twin Cities and National Historic Landmark, now reimagined as the A-Mill Artist Lofts and designed by BKV Group, the community of affordable artist apartments located just off the Mississippi River, utilized state and federal historic tax credits and the Low-Income Housing Tax-Credit (LIHTC) programs.

(BKV Group)

Adaptive use redevelopments can help bring more equity to riverfronts because they often tap into available state and federal historic tax credits, along with Low-Income Housing Tax-Credit (LIHTC) programs that are essential to get such projects to pencil out. A-Mill Artist Lofts, also developed by Dominium, is an example of an affordable riverfront development in Minneapolis that, like Upper Post Flats, used these financing methods. As a conversion of the historic Pillsbury A-Mill, an iconic Twin Cities historic landmark completed in 1881, the design and construction process was closely monitored and approved by several state agencies and the National Park Service to ensure the project complied with historic design requirements.

Cities can also set aside a percentage of their remaining undeveloped riverfront land for affordable or mixed-income housing. This approach would be similar to what local governments are mandating through equitable transit-oriented developments (ETODs), which incentivize or require affordable housing and community-oriented commercial space near transit hubs that might otherwise be inaccessible to lower-income households.

Cities that lose sight of developing and maintaining an urban infrastructure that is socioeconomically diverse face a long road to recovery. Now is the time to ensure that the future of downtowns—including ones with prime riverfront real estate—is an inclusive one, with space for all to live, work, and play.

Several transformational affordable and mixed-income developments are helping to bring more equity to the riverfronts of major U.S. cities:

Located in Brooklyn’s Greenpoint neighborhood, 1 Java Street is an 834-unit multifamily project being developed and constructed by Lendlease, occupies a full city block on the East River.

Lendlease

1 Java Street in New York City

Located in Brooklyn’s Greenpoint neighborhood, this multifamily project, being developed and constructed by Lendlease, occupies a full city block on the East River. When completed in 2026, the 834-unit property is to feature a new public waterfront esplanade with a living shoreline. The site has a direct connection to the publicly accessible India Street Pier, which was improved as part of the project and is served by the East River Ferry. At 1 Java Street, 30 percent of the units—251 apartments—are designated as affordable housing by the Affordable New York Housing Program. Residents will also benefit from the community’s sustainable design. In addition to being all-electric, 1 Java Street will feature one of the largest multifamily residential geothermal systems in the country, significantly reducing carbon emissions.

Marine Drive Apartments in Buffalo, New York

Chicago-based Habitat has been enlisted by the Buffalo Municipal Housing Authority to redevelop Marine Drive Apartments at Canalside, an affordable, transit-oriented 650-plus-unit development connected to the city’s Buffalo River waterfront. The current structures are more than 70 years old, have fallen into disrepair, and will be torn down in phases to not displace residents as part of one of the biggest redevelopment projects in the city’s history. The recently approved $400 million project, which will expand the number of affordable units on site through a mix of low-, mid-, and high-rise buildings, is being funded partially through LIHTC equity, tax credits from New York state’s Brownfield Cleanup Program, and loan programs from the state Housing Finance Agency. It is expected to break ground in 2025.

Wendelin Park in Chicago

Chicago-based Structured Development’s Wendelin Park, a new mixed-income community on Chicago’s Near North Side, is steps from the North Branch of the Chicago River, near the Wild Mile, the city’s first floating eco-park. Replacing an industrial site, the Wendelin Park development comprises three residential buildings situated around a new publicly accessible park. They include The Seng, a 34-unit, all-affordable condo building—the largest of its kind ever built in Chicago—and Post Chicago, the city’s largest co-living community, with 431 beds. Foundry—a 27-story, 327-unit market-rate apartment tower—was completed late last year. In addition to enhancing walkability, the park features a community garden, dog run, children’s climbing and play area, and 20-foot sculpture.