Demand is surging for senior housing as America’s population ages, but supply continues to lag. That gap is one reason investors in ULI’s 2025 Emerging Trends report rated the sector second highest for the best risk-adjusted returns over the next three years.

Supply and demand dynamics don’t tell the whole story, though: senior housing development tends to thrive at the upper end, where seniors with means can afford to live in a continuing care retirement community. It also thrives at the lower end, where government subsidies support housing and health care for seniors with fewer resources.

“The big challenge in senior housing is for middle-income people, particularly if they need some kind of caregiving,” says Lisa McCracken, head of research and analytics for NIC (National Investment Center for Seniors Housing & Care), headquartered in Annapolis, Maryland. “If you need supportive housing or assisted living, it’s either private pay or Medicaid. But . . . a massive number of people in the middle . . . can’t afford private pay and don’t qualify for Medicaid.”

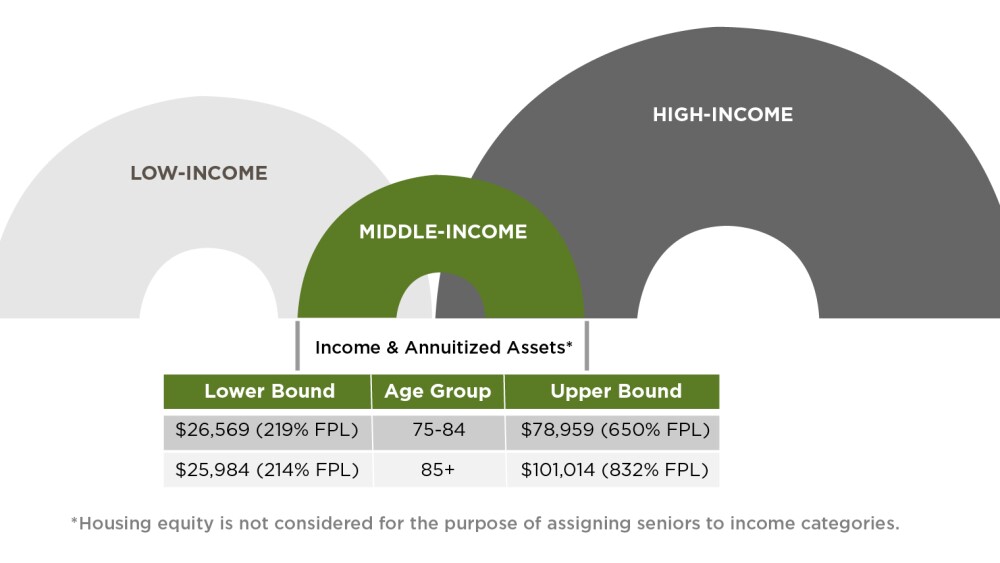

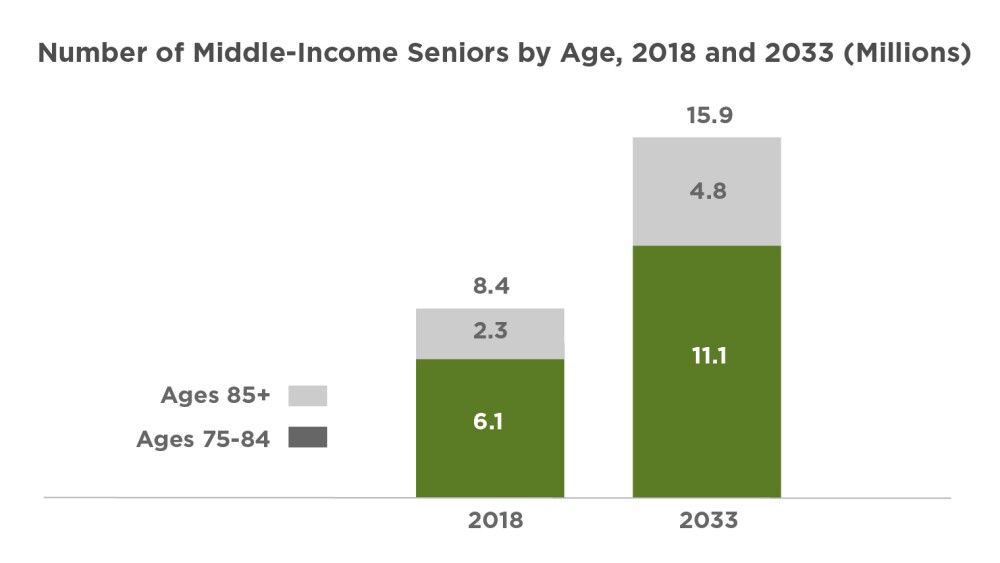

Researchers at NIC and NORC at the University of Chicago estimate that there will be 16 million “forgotten middle” or “missing middle” seniors, age 75 and older, in the United States by 2033, who will constitute 44 percent of all older adult households. Middle-income seniors typically earn 80 percent to 120 percent of area median income (AMI), according to McCracken.

More from Emerging Trends 2025

Unaffordable rents

Dale Boyles—San Diego–based managing director of senior housing at Alliance Residential, a multifamily developer—says that middle-income seniors can generally afford a rent of $2,500 to $4,500 depending on their location, rather than the upscale rents of $5,000 to $15,000 that many senior living communities charge.

“Many people think the answer is a low-service environment in which middle-income seniors pay an affordable rent and then fend for themselves to engage housekeeping or home health services as they age,” Boyles says. “But that doesn’t work for someone with a $3,000 monthly budget if their rent is $2,000. The cost of food, medications, and services can be much higher than $1,000.”

Older seniors are more likely to have mobility limitations and cognitive impairments that make it harder for them to live independently, according to NIC. Paid caregiving will be a necessity for many of them because the majority will be unmarried in 2033, and many do not have children living nearby.

Affordable housing is just part of the equation for middle-income seniors as they age. Help with daily living and health concerns is the second half of the challenge.

According to researchers at the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University, only 14 percent of adults age 75 and older who live alone can afford a daily home health aide visit after paying for housing and other living costs, and just 13 percent can afford an assisted living facility in their area.

Financing roadblocks to overcome

Senior housing for the forgotten middle faces the same challenges as all real estate development, including the cost of capital, construction costs, and the limited availability of capital. In addition, there are the challenges of serving a market that has budgetary constraints, and the need to provide more than housing alone.

“Middle-market senior housing faces financing challenges due to high equity requirements, limited subsidies, and rising construction and interest costs,” says Jon Fletcher, CEO of Presbyterian Homes & Services, a nonprofit senior housing provider based in St. Paul, Minnesota. “Traditional multi-housing funding models prioritize luxury or low-income housing, leaving middle-income seniors underserved. Investors and lenders are keen to see middle-income product be successful, but they also often see middle-market housing as a lower-margin product, making it difficult to secure financing.”

The margins are extremely tight, and operations costs have risen significantly in the years since the start of the pandemic, Boyles says. Caregiver wages that were $13 to $14 per hour are now in the $20 to $25 range, he says. Inflation has raised food and utilities costs.

The problem, Boyles says, is scale.

“There’s no Walmart in our industry, because 60 percent of the total operating costs is for labor,” Boyles says. “It’s people helping people with their physical and emotional needs, so it’s hard to be really efficient.”

Those dynamics limit the appetite of lenders for middle-income senior housing.

“Banks don’t lend directly to developers much for senior housing because this is an operations-driven business,” says Kathryn Burton Gray of Seniors Capital LLC, based in Laguna Beach, California. “Some operators are also developers, and there are developers who have a strong strategic partnership with a well-known operator, but otherwise it’s very difficult for a developer to get a loan for middle-market senior housing.”

To remain viable, middle-market senior housing requires long-term investment and careful cost management, Fletcher says. “Acquisitions and repositioning existing properties may yield more stable financial returns at middle-income price points when compared to new construction in today’s market,” he says. “Developers should focus on operational efficiency, moderate rent growth, and strategic partnerships to ensure sustainable success and affordable services delivery models.”

Senior housing typically has the most community support of any kind of development, according to Alexandra Vondeling, a senior associate with Opticos Design, a Berkeley, California–based architecture firm that specializes in missing middle housing.

“Sometimes a city will put out an RFP [request for proposal] for a senior housing developer and operator for [city land] and will hold onto the lease for a certain period of time,” Vondeling says. “Churches sometimes want to build attainable housing and have land that can be used. Any type of organization that can reduce land costs can help subsidize development costs.”

Developers who have met the challenge of getting costs to pencil out have often pieced together a patchwork of financing solutions, McCracken says.

“They’ve gotten grants, upfront capital, tax credits, or tax-exempt bonds to help offset costs,” she says. “We think there are opportunities for public/private partnerships because developers with private capital would come to the table for LIHTC [Low-Income Housing Tax Credit] deals. But these need to reach the lower-to-middle-income seniors, not just affordable housing levels. This would be like workforce housing incentives, except at the senior housing level.”

Making middle-market housing work

There are multiple approaches to address middle-income senior housing, including solutions on both the real estate side and the operations side. From a design and architecture perspective, forgotten middle housing works best if it’s part of a walkable community that encourages socializing with neighbors, Vondeling says.

“The types of design that resonate with seniors include cottages with courtyards and pocket neighborhoods that create community,” Vondeling says. “We’re also encouraging zoning changes that allow for ADUs [accessory dwelling units] for seniors to live near their family. Another option is a multigenerational home with a section carved out for the senior, or an incremental addition to a home.”

Solving the shortage of housing for the forgotten middle seniors requires an operations focus married with a real estate focus, Burton Gray says.

“Housing for middle-income seniors requires a massive responsibility of engagement and programming,” Burton Gray says. “Affordability and enrichment are both needed to make people healthier and happier.”

Middle-income senior housing requires an integrated approach that includes housing, health care, and social infrastructure, Fletcher says. “The rising costs of health care, assisted living, and long-term care present significant barriers,” he says. “A successful model combines independent living, home health care, and social engagement to ensure long-term stability.”

Most successful forgotten middle senior housing communities offer independent living, McCracken says, but a few, such as Innovation Senior Living, a senior housing operator based in Winter Park, Florida, provide assisted living services.

“Since development at any level is extremely costly, we focus on buying properties as inexpensively as possible—under $80,000 per unit,” says Pilar Carvajal, Innovation Senior Living’s founder and CEO. “We make some of the units semiprivate to meet the needs of lower-middle-income seniors. Then we partner heavily with home health care aides, hospice care, and therapists, so our residents get what they need without putting people on our payroll.”

Replicating the model

Carvajal says that opportunities exist to replicate this model by repositioning hotels, multifamily buildings, and trailer parks with the addition of a community center.

Merrill Gardens, a senior housing developer based in Seattle, Washington, started its Truewood by Merrill division—which includes independent living and assisted living communities—about five years ago, when they acquired approximately 20 communities that had been built for senior living but were no longer serving that populace.

“Our idea was to create a Residence Inn–level of senior housing instead of the JW Marriott,” says Tana Gall, Merrill Gardens’ president. “The goal was to serve middle-market seniors, some of whom have a housing budget capped at $3,500, and others who could afford more rent but are more practical. Or they’re just not ‘fancy’ and would be happy with good quality, without the bells and whistles.” For example, Gall says, instead of serving an array of made-to-order breakfast choices every day, Truewood by Merrill offers a high-quality, freshly cooked breakfast with just one choice to lower costs.

The company focused on the residents and services, and it was careful not to overspend on renovating the buildings, says Jason Childers, COO of Merrill Gardens. “We were able to acquire the buildings at a great basis, and we just worked with what we had,” he says. “We focused on ways to drive down costs to lower rents, starting with a goal to lower labor costs by 30 percent.”

Opportunities to manage operating costs without compromising quality of life include:

- Adjusting food services. At Truewood, the company held focus groups and found that residents were interested in flexibility and didn’t necessarily want to go to the dining room three times a day. Carvajal says that, in her communities, she reduces food costs by having one special gourmet meal per month instead of on a nightly or weekly basis, as luxury senior housing facilities often do.

- Streamlining operations. Many of Carvajal’s properties are clustered, so she can have one executive director for several properties. She brings as many operations into the corporate office as possible, such as eliminating business managers in every community. “I negotiate group purchases for everything, and negotiate with Medicaid and the insurance companies, too,” she says.

- Cross-training employees. Childers says Merrill was able to shrink labor costs by tracking the daily ebb and flow of employee activity and having workers take on multiple tasks. For example, team members who serve food and clean up after breakfast often had a midmorning lull, which they now fill by working at the front desk or managing an activity. “Our employees are multifunctional and learn about the business, and can grow in their careers,” Childers says. “We found out that one of our dining room servers is a great musician, so he plays piano for our residents now, too.”

- Relying on volunteers and residents. At Truewood, residents, family members, volunteers, and staff lead activities and provide transportation, which reduces paid staff time. “One of our residents is a former high school art teacher, and now she teaches other residents,” Gall says. “Our intention is to have a robust calendar of activities. It turns out that resident satisfaction goes up when they feel like they have a job and a purpose.”

- Developing relationships. Partnering with volunteer organizations, family members, home care organizations, home health aides, physical therapists, and physician groups have helped Truewood take the pressure off staff and reduce operations costs, Gall says. These strategic partnerships also help develop a sense of community among residents, volunteers, and staff.

Presbyterian Homes & Services has followed a similar path by developing a scalable middle-market model, Fletcher says. “We have leveraged a mixture of new developments, affiliations, acquisitions, and joint ventures; minimized overhead; and implemented a hub-and-spoke structure to centralize services and amplify the benefits of concentrated scale,” he says. “We maintain affordability by attempting to link rent increases to CPI rather than market-driven pricing and using creative financing strategies.”

Streamlined services and operational efficiency are key to the success of these middle-market senior housing communities.

“Forgotten middle housing for seniors needs capital and a model to replicate,” McCracken says. “We have the bookends covered—affordable senior housing and luxury senior housing—so we need to look at the solutions, such as design changes, scaling back amenities, and strategic partnerships. There needs to be a public element and private groups who are passionate about this.”

Related Reading: