Chicago’s plan to transform the city’s entire portfolio of public housing is still unfinished after 13 years, more than $1 billion in investment, and the displacement of tens of thousands of public housing residents–displacement that continues to this day for some families.

But the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) has managed to turn some of its strongest critics into supporters, including one housing expert who carefully tracked Chicago’s public housing residents over more than a decade of tumultuous change. She found that people served by the CHA have significantly better housing now than when the agency began its transformation in 2000.

“Nobody lives in places that are as dangerous or as poor as the places where they were,” says Susan J. Popkin, director of the program on neighborhoods and youth development for the Urban Institute.

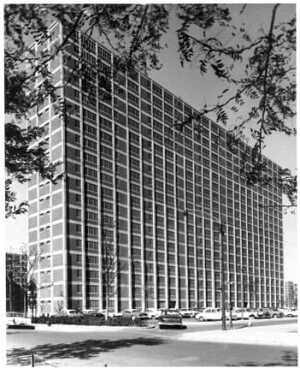

The CHA’s Plan for Transformation began in 2000 with a promise to demolish, rebuild, or renovate Chicago’s 25,000 units of public housing. High-rise projects like Cabrini-Green and the Robert Taylor Homes had become synonymous with high crime rates and urban decay.

Thirteen years later, after demolition of nearly all the CHA’s largest high-rise public housing projects and a flood of new construction, the agency has 17,000 units of public housing. Chicago’s newly built public housing apartments are often mixed in with market-rate housing that looks no different but that can rent to families earning significantly more than the average public housing resident.

Experts agree that the new public housing is attractive, but there is a lot less of it than the CHA planned. “Physically, the transformation has been amazing, . . . but they are behind,” says Lynn Ross, executive director of the Terwilliger Center for Housing at the Urban Land Institute.

In part, the CHA has fallen behind on its goals because the housing crash and financial crisis have made it difficult to find the money needed for large, complicated redevelopments. More recently, Congress cut the funding for the federal HOPE VI program, which specialized in big redevelopments of public housing like that in Chicago.

To help make up for public housing that has not been built yet, the CHA now provides federal housing choice vouchers to 37,000 households, including many former public housing residents. These vouchers help pay the rent at privately managed rental housing properties for many displaced public housing residents.

The Urban Institute has tracked Chicago’s public housing residents throughout the process. In 2000, the CHA had just finished several years of being controlled directly by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). “I was very concerned what would happen to the residents,” says Popkin. “Chicago had earned its place as the worst housing authority in the country. When HUD took over, it took them three years to balance the books.”

In those early days of public housing redevelopment, authorities often were unable to say where public residents had gone after a redevelopment, let alone whether their housing situations had improved. Chicago proposed to transform not just one public housing community, but its entire CHA portfolio. “The Plan for Transformation was probably the most aggressive plan for public housing transformation in the country,” says Ross.

Surveys of the public housing residents in Chicago, however, show they think their housing situation has improved, both for residents of new public housing and households living in private housing with help from vouchers. “They almost always went to physically better housing,” says Ross.

In particular, former public housing residents feel safer and less economically isolated in their new homes. “Feeling safer is huge,” says Popkin. “We see some reductions in anxiety and mental health just from moving.”

Displacement still had a heavy cost for residents, however. Children who changed schools often fell behind. Residents were often separated from support networks. “We didn’t understand what it meant to move that many people at once, that dramatically, that quickly,” says Ross.

Supportive services can help, according to the Urban Institute. Residents with intensive case management and supportive services from the Chicago Family Case Management Demonstration now show significantly lower rates of depression, better physical health, and higher rates of employment. However, many adults still struggle with extremely high rates of debilitating chronic illness that keeps them from full-time employment, according to the Urban Institute. Many children still grapple with the fallout from growing up with chronic violence.

Many commentators still believe that displaced public housing residents flooded into the Chicago suburbs. Instead, research shows that displaced residents mostly stayed within Chicago’s city limits, where they largely had access to Chicago’s extensive bus system and other services. “They didn’t go too far. Many moved to poor, African American neighborhoods of the south and west sides of the city,” says Popkin.

The CHA redevelopments also led to a small net decrease in crime overall during a study period in which crime declined significantly, according to the Urban Institute. Crime rates fell substantially near public housing demolitions, but fell less than expected in destination neighborhoods for households relocated with vouchers. More thoughtful relocation strategies that support both assisted residents and receiving communities could help fight crime better in future developments, says Poplin.

The CHA’s work is not done. In April, officials announced “Plan Forward: Communities That Work,” a plan to acquire homes in neighborhoods across the city for rehab to help finish the remaining housing in the CHA’s original plan. The new plan would also boost economic activity around CHA sites and provide job training and educational opportunities for voucher holders.