“Obviously, if you were to set out to build millions of square feet of development space, you wouldn’t necessarily start by saying, ‘Let’s build it on a platform over an operating rail yard,’ ” explains Thad Sheely, senior vice president of operations for development firm Related Companies. “That drastically increases the degree of difficulty. Basically, we’re building the ground. But that’s only one of the things that make this project unique.”

Register for ULI Fall Meeting in NYC

New York–based Related is teaming up with Toronto-based Oxford Properties to build Hudson Yards, a $20 billion project that is the largest private real estate development in the country and the biggest in New York City since Rockefeller Center was erected in the 1930s. The 28-acre (11 ha) West Side site—which is located between 10th and 12th avenues from West 30th to West 34th Street—will include more than 17 million square feet (1.6 million sq m) of commercial and residential space, five office towers, 5,000 residences, a 150-room luxury hotel, more than 100 shops and 20 restaurants, a cultural center, a school, and 14 acres (5.6 ha) of public space. The eastern half of the project, which will include four of the five office towers, is scheduled for completion in 2018.

But the project’s scale pales in comparison with the outsized engineering feat that makes it possible to be built. In order to make use of a site already occupied by a working rail yard—including more than 30 tracks for the Long Island Rail Road and three train tunnels, with a fourth under construction—most of the development will be built atop two steel-and-concrete platforms. That base, and the buildings on it, will be supported by hundreds of concrete-filled caissons, which will be drilled between the rail lines into the bedrock.

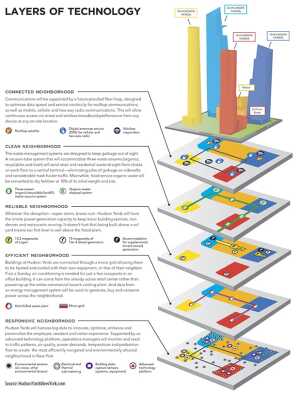

In addition to its dramatic underpinnings, the cluster of skyscrapers—all but one of which will be built on manmade land—will use technological advances to depart from convention in other ways. Related has dubbed Hudson Yards “Tomorrow’s City, Today”—a tagline that sounds as if it were written by Norman Bel Geddes, the designer of the Futurama exhibit at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Hudson Yards will have 13.2 megawatts of cogeneration capacity to supply electricity and heat—even if the larger utility company grid goes down—and its buildings will be interconnected so that they can share heat and air-conditioning resources as well. Also, trash will never pile up on sidewalks thanks to a below-the-surface disposal system that will whisk away garbage through pneumatic tubes at 45 miles (72 km) per hour.

Beyond that, a vast number of sensors embedded in the site’s infrastructure will collect mountains of data on everything from temperature and air quality to pedestrian and vehicle traffic. That information, which will be scrutinized in real time by managers in an effort to fine-tune Hudson Yards’ operation, will also be shared with New York University (NYU) researchers, who will turn Hudson Yards into a laboratory for studying urban life and finding ways to improve its quality.

The New West Side

The West Side district around the new project has been gradually evolving since 2005, when the city rezoned what the New York Times described as “a mishmash of rail yards, tunnel ramps, and parking lots” to encourage development. “It was seen as the last frontier,” says Lynne Sagalyn, a professor of real estate at Columbia University. “It’s a huge district next to west Manhattan’s mid-commercial district, so it’s an area that’s ripe for incremental growth.”

The idea of manufacturing real estate by capping rail tracks actually is a time-honored practice in New York City. “It’s exactly what New York did with Park Avenue,” says Sheely, recalling how the New York Central Railroad put its tracks and yards underground and capped them with a steel deck in the early 1900s. “No one even thinks of them being there today.” Putting platforms over Hudson Yards actually was proposed back in 1996 by urban planner Alexander Garvin, who later worked on the city’s unsuccessful bid to host the 2012 Summer Olympic Games, which called for building a new stadium in the area. And another developer, Brookfield Office Properties, is building the $4.5 billion Manhattan West office development a block east of Hudson Yards, on a 2.6-acre (1.1 ha) platform over rails as well. Thornton Tomasetti is the project’s structural engineer.

Even in light of these mammoth undertakings, the immensity of Related’s project remains striking. The eastern half of the platform, construction of which began this spring, will be supported by 300 caissons ranging from four to five feet (1.2 to 1.5 m) in diameter, which will be set 20 to 80 feet (6.1 to 24.4 m) deep—into the bedrock. That section alone will require 25,000 tons (22,700 metric tons) of steel and 14,000 cubic yards (10,700 cubic m) of concrete and will weigh more than 35,000 tons (31,700 metric tons) when it is completed. Because the location of the tracks and tunnels limits the placement of caissons, only 38 percent of the site can be used to support buildings.

While Sheely notes that the platform construction is based on time-honored civil engineering techniques, building the platforms without disrupting train service makes the process far trickier. As a March 2014 article in Wired magazine detailed, lead platform engineer Jim White has used computer models to coordinate the drilling and truss-laying around the hour-to-hour train traffic so that work can be done whenever a window of opportunity is available. According to the article, the project will require just four scheduled track closures during the 2.5 years it will take to build the platform.

“I think the platform is fascinating,” Sagalyn says. “As cities become [denser], it’s important to capture those kinds of sites—especially when they’re on top of transit. And if a profit-making developer shows that it can be done, and the huge cost of upfront infrastructure can be carried, that will make other people look at it as a case study and ask if it can be done in other places.” The expense and difficulty of the platform construction imposed certain requirements upon the

Hudson Yards project. In order for the expense to be justified, the project had to include high-density towers that would maximize use of the new land being created. “You need high density to make those numbers work,” she explains. “It will only work in cities where you have high density or high demand.”

Sagalyn gives Related high marks for how the developer handled the perils of going big. “The risk here has been mitigated by multiple equity sources and major tenant commitments,” she says. On the latter front, Related managed to line up Time Warner and high-end retailer Coach as tenants.

The necessity of thinking big also gave Related a novel opportunity, Sheely says. “Other projects in New York are infill projects, where you build one building and you control nothing beyond the property line. Here, our property line includes acres of open space and parks and other interesting things. You can do more if you can control all that.”

A Resource-Sharing Grid

That sort of control will enable the developers to innovate when it comes to energy use. The central plants of Hudson Yards’ mixed-use buildings will be connected through a thermal loop, which will enable them to exchange heat and chilled water with one another. That synergy could lead to a significant reduction in waste and energy costs, according to Charlotte Matthews, Related’s vice president for sustainability. If there are a few people in offices on a Sunday, for example, the building will not need to start up its whole central plant to keep those offices cool. Instead, the building can import excess resources from the retail building next door, which also will have a lower marginal cost and consume less energy.

“It is the first multitenant microgrid,” Matthews explains. “Most microgrids that people talk about are like hospitals or university campuses: they’re more akin to district plants. In our scenario, it can be the model for retrofitting microgrids into existing neighborhoods, because each building still has its own central plant. And we’re creating both a physical interconnection and a technology platform with monitoring, so the tenants can see what their real-time cost will be for generating hot or cold water on site, versus importing it from the thermal loop.”

Matthews says the buildings at Hudson Yards will feature other efficiency and cost-saving measures as well, including smart lighting that will notify the building manager by e-mail if a fixture flickers or goes dark, and wireless, movable occupancy sensors that will turn lights on and off automatically.

Another bit of advanced technology will spare Hudson Yards residents from seeing and smelling garbage trucks picking up mounds of trash bags on street corners or emptying Dumpsters. Instead, refuse will be removed through a trash disposal system created by Envac, a Swedish company. Recyclables, food waste, and regular trash will go down separate chutes, and the refuse will be sucked through a pneumatic tube to a central facility where a dehydrator will shrink it to 20 percent of its original weight and volume.

Matthews says that Related is installing the system in part to get ahead of what it expects will be more stringent future regulatory requirements for waste handling. Last year, the University Transportation Research Center at the City University of New York issued a report that examined using pneumatic tubes to collect and transport trash on a larger scale in the city and concluded that the practice would reduce energy use for garbage collection by 60 percent and resulting greenhouse gas emissions by more than half.

Big Data on a Massive Scale

Hudson Yards is planned to be one of the first large examples of what technologists call a “quantified community.” Sensors embedded throughout the development will gather and measure data on a vast array of categories ranging from water consumption and waste generation to heat patterns and air quality. Energy consumption in apartments will be measured by smart thermostats that will report energy use as well. Instruments that measure light outside the visible spectrum will allow Hudson Yards to monitor plumes of carbon dioxide emissions in real time.

Many of these gadgets will communicate wirelessly through the distributed antenna system built into the complex. The antennas also will allow phones and other wireless devices to log into a massive fiber optic–equipped wi-fi network that will eliminate dead zones and provide more bandwidth, according to Sheely. “We’ve done all the hard work to get the connectivity on our site,” he says.

While cities around the world are using data collection and analysis to deal with problems such as traffic and crime, the effort at Hudson Yards is far broader in scope. “This is the most systematic approach to collecting data about a neighborhood that’s ever been attempted,” says Constantine Kontokosta, deputy director at NYU’s Center for Urban Science and Progress, which is partnering with Related to analyze the data.

While all the details of the plan are still being worked out, Sheely says that the enormous amount of data most likely will be transmitted to the cloud and managed by an outside information technology company, so that the development’s managers can access the database remotely in their on-site operations center. “Basically, we’ll be the funnel and collect the data so they can put [the information] though their spin cycle in the cloud, and then provide an interface for us to be able to access the information,” he says. “That way, we won’t need to have a big server farm on campus.”

One obvious benefit is the ability to closely monitor and optimize energy use at Hudson Yards—something that Sheely claims will result in clear-cut cost savings. He seems confident that it will create value in other ways as well—though, like other technological revolutions, the benefits are not entirely clear at the outset. “We’re at an interesting crossroads with all of this—‘big data,’ the ‘internet of things,’ whatever buzzwords you want to toss out,” he says. “There’s something here, but Google and Apple haven’t figured it out yet, either. But this is a road we have to be on, but no one knows where it goes . . . our focus has been to get the hardware right, so that we have the bandwidth, the connectivity, two-way communication, and the ability to upload and download and collect data.”

Sheely also envisions getting residents and visitors to “opt in” and voluntarily provide information about their activities via their smartphones and other devices, in exchange for services. Eventually, though, data on transportation use at Hudson Yards may enable management to guide residents to the quickest way to get to work, or the best spots to hail a taxi.

Meanwhile, the NYU researchers will be studying the same data stream on an ongoing basis, in an effort to discern patterns of how residents rely upon various transportation modes, or whether their use of the development’s open spaces has beneficial health effects. “There’s a potential here to understand how a neighborhood functions,” says Kontokosta, who emphasizes that any personally identifiable information would be provided voluntarily and kept confidential. “We want to know how people really interact with their built environment, and how they are affected by environmental conditions.” That information, he says, will enable researchers to test long-held “rule of thumb” ideas about urban design to see whether they are truly valid or need to be rethought. “Ultimately, we hope to use [these] data to improve the quality of life in cities.”

The Architecture of Adaptability

The master plan for Hudson Yards was devised by the architecture firm Kohn Pedersen Fox (KPF), which also designed two of the towers in the development’s east yard.

One of the biggest aesthetic challenges facing Hudson Yards was to create a development that connected with the rest of Manhattan, rather than standing in isolation. “We’re dealing with buildings of a very large scale, as you know,” explains William Pedersen, a founding partner of KPF. “It’s essential that they be deferential, because if not, their scale alone can be disturbing . . . such an enormous physical presence, unless it is sculpted and creates responses that are very specific to the context, will feel threatening.”

Pedersen sought to solve this problem through design elements that would make gestures to both their surroundings and the other buildings. As an example, he cites the 52-story, 1.7 million-square-foot (158,000 sq m) structure 10 Hudson Yards, which was the first tower to begin construction. When completed in 2015, the tower in the development’s southeast corner will be the only one in the project constructed entirely upon solid ground and not on the platform.

Pedersen found an intriguing way to address the building’s surroundings. He allowed the High Line—a public park built on a historic freight rail line elevated above the West Side—to penetrate underneath the tower through a 60-foot-long (18.3 m) public passageway, so that the building will interact with the park and its visitors. Inside the building, a dramatic atrium “becomes the terminus of the High Line as it moves from south to north,” he says.

The atrium itself was the result of discussions between KPF and Coach, the retailer whose global headquarters will be located in the building. (Other major tenants in the building include beauty product manufacturer L’Oréal, which has leased space for its main U.S. office, and business software giant SAP.) “Lew Frankfort, who is the Coach executive chairman, said to us, ‘I always envisioned a campus for my facility,’ ” Pedersen recalls. “That was our impetus for drawing out the individual volume and creating the atrium, which enables their workforce to focus upon this central stage, and for the building to become more complex in its organization.”

“Coach is doing an interesting thing with their space,” says architectural critic and author James S. Russell. He says the atrium provides “the sense of everybody working together . . . I think it’s closer to the future model of the skyscraper, which has got to be simpler and foster creativity.”

Pedersen’s notion of architectural design responding to user input, in a sense, fits with the larger concept of a development project that has been equipped technologically to study its occupants and adapt to how they use the built environment. “We’re really trying to make it—for lack of a better word—smart infrastructure,” says Sheely.

Patrick J. Kiger is a Washington, D.C.–area journalist, blogger, and author.