On January 13, 1939, a group of commuters held a wake onboard a ferry crossing San Francisco Bay. The next day, trains were to start running on the Bay Bridge from the East Bay to the newly constructed Transbay Transit Terminal, and ferry service would end. A reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle watched pallbearers in black top hats toss a model ferryboat off the deck into the waves, mourning the imminent loss of their beloved form of commuting.

Designed in the art moderne style by the local firm Pflueger and Brown, the Transbay Transit Terminal would soon eclipse San Francisco’s Ferry Building as the city’s most important transit hub, serving as many as 26 million passengers a year during its peak years in the 1940s. But automobiles gradually supplanted trains—the last train crossed the Bay Bridge in 1958—and the terminal became a bus facility. Although the terminal became outdated and shabby, plans to replace it failed to materialize for a long time. So did plans to link it to the northernmost end of the Caltrain commuter-rail line, which had a less-than-optimal location more than a mile (1.6 km) from the edge of the city’s financial district.

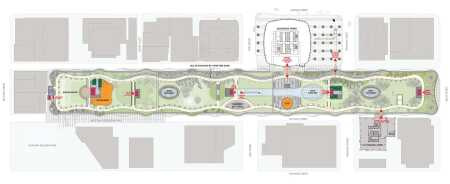

Today, San Francisco anticipates the 2017 opening of a new Transbay Transit Center, envisioned as the “Grand Central Station of the West.” Unlike Grand Central, it will have a 1,400-foot-long (430 m) elevated linear park on its roof. The 1 million-square-foot (93,000 sq m) facility is ultimately expected to accommodate more than 100,000 passengers each weekday and up to 45 million people a year, bringing Caltrain within a block and a half of the city’s financial district, connecting the city to Los Angeles via California’s future high-speed rail line, and linking to nine other local and regional transit systems.

Overseen by the Transbay Joint Powers Authority (TJPA), the Transbay program includes the creation of the Transit Center District. The high-density mixed-use neighborhood currently under construction will have retail space, hotels, open space, market-rate housing, and a high proportion of affordable housing.

“We’re building a place where people will be able to take public transit to all points of the Bay Area, the state, the region, and the United States. But it will also be a place where people can come and take a break from their daily lives through our retail, restaurants, public art, parks, gardens, amphitheater, and plazas,” says Maria Ayerdi-Kaplan, executive director of the TJPA. “We’re hoping that people will see this as more than just a transit station.”

To guide development in the area, the city’s planning department, in coordination with the TJPA and the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency (now the Office of Community Investment and Infrastructure), created the Transit Center District Plan (TCDP). The TCDP concentrates future growth in the district by eliminating density caps and allowing a limited number of buildings to exceed the city’s 550-foot (150 m) height limit. It also calls for widening sidewalks, providing landscaping and bicycle parking, and increasing the amount of public open space. The project ultimately will add more than 11 acres (4.5 ha) of open space to the neighborhood.

Paving the Way to Transbay

The ambitious project owes its existence not only to decades of planning, but also to the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. The quake damaged the elevated double-decked Embarcadero Freeway that looped from the Bay Bridge to the waterfront. The city elected to tear down the freeway and its off-ramps in the early 1990s rather than replace them, a move that reconnected the city to the waterfront and freed up multiple parcels of land for redevelopment. Over the next decade, the city undertook studies for a new terminal and an extension of Caltrain.

In 2003, the state donated land to the project, including the site for the new transit center and an additional 12 acres (4.9 ha) of developable land. The TJPA was given the power to auction off parcels to developers, with revenues going toward the Transbay program. The TJPA also receives property tax increment funds from the properties developed on those parcels, thanks to creation of the Transbay Redevelopment Area in 2005.

In fall 2006, the TJPA held a competition to select the design and development team that would design the new transit center and design and develop the adjacent Transbay Tower; the TJPA would serve as developer for the transit center itself. Nearly five blocks long, the new transit facility would parallel Market Street one-and-a-half blocks away. The privately developed Transbay Tower would be the city’s tallest building, more than 1,000 feet (300 m) high.

A year later, after ranking the three finalists on design excellence, functionality, and financial feasibility, a jury selected the team of the San Francisco office of Hines and the New Haven, Connecticut, office of Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects (PCPA), and the Berkeley, California, office of PWP Landscape Architecture (PWP). Hines/PCPA/PWP was the only team to propose placing a park on the transit center’s roof. “We realized that this building was going to be at the center of a very dense, new high-rise neighborhood and that the transit center itself was going to give rise to transit-based development,” says Fred Clarke, senior principal of PCPA. “And most of the buildings surrounding the Transit Center would be looking out onto its roof.”

The team decided that a 5.4-acre (2.2 ha) park running the length of the transit center’s roof would express San Francisco’s strong value for sustainability. PWP Landscape Architecture worked with Pelli Clarke Pelli to design the park, which includes cafés, gathering places, overlooks, and an amphitheater that can hold up to 1,000 people.” “This part of town is starved for open space,” says Paul Paradis, senior managing director of Hines in San Francisco. “And when we priced it with our construction experts, we realized that the pricing was not substantially different from what it would be with an elaborate sculptural roof.”

Pedestrians will have numerous ways to reach the park, including escalators, elevators, stairways, and a gondola rising from a new street-level plaza called Mission Square, also designed by PWP Landscape Architecture. “The reason that we included the gondola is so that the average person walking by would know that there is something on top of the transit center that’s public and available,” says Paradis. In addition, several of the new buildings around the transit center, including the new tower, will connect to the park by a bridge.

Making an attractive pedestrian realm was another key part of the design. “Large transit centers, particularly since the 1960s, have tended to be dark, dirty, unfriendly, and in many cases unsafe,” says Clarke. “We wanted to completely undo that perception. Particularly at the street level, this building needed to be light, open, bright, welcoming, and supportive of adjacent retail and housing. So it’s very transparent, very permeable—exactly the opposite of the old transit center.”

Large columns lift the building’s perimeter off the ground, thus sheltering streetfront retail space and creating wide sidewalks for pedestrians. The glazed lobby provides views into and out of the transit center. “Light columns” bring daylight from skylights down through floor openings to multiple levels, including the lowest. Perforated, pearlescent white metal panels will curve around the exterior of the Transit Center, serving as a lace-like screen. The pattern of the perforations, based on a geometrical pattern devised by British mathematical physicist Roger Penrose, symbolizes the intersection of mathematics, science, and art.

Retail space also is envisioned as crucial to the transit center’s success. “Transit centers built in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s tend to not have any life at the street,” Clarke says. “We really wanted to build as much retail in as we possibly could, so there are two levels of retail. When the building is fully built, there will be over 100,000 square feet [9,300 sq m] of retail.”

The Hines/PCPA team was also the only one to propose that the tower be entirely given over to office space rather than being a mix of office, residential, and hotel uses. “There was generally a desire by the TJPA to have a mixed-use project,” says Paul Paradis. “But when we asked them about it, it wasn’t a hard-and-fast requirement. We preferred the economics for an all-office tower. You don’t have to coordinate numerous elevator systems and front doors. And in a neighborhood like this one, there is a rich mix of uses within a block or two.”

In 2012, the San Francisco Planning Commission granted final planning approval for the tower to proceed, and Hines formed a joint venture with Boston Properties to acquire the tower site from the TJPA. Hines would sell all but 5 percent of its ownership interest in the joint venture to Boston Properties in March 2013, making Boston Properties the lead developer, with 95 percent ownership of the site. The joint venture then purchased the land, with the proceeds going to the Transbay Transit Center project.

In April 2014, the joint venture struck a deal with Salesforce.com, a provider of customer relationship management software, to lease 714,000 square feet (66,000 sq m) of space for its headquarters—more than half of the 1.4 million-square-foot (130,000 sq m) building. The structure was renamed Salesforce Tower.

“We were lucky to negotiate the largest lease in San Francisco’s history with Salesforce.com as an anchor tenant,” says Michael Tymoff, senior project manager of development for Boston Properties. “We have a lot of activity and interest from prospective tenants for the balance of the building. Salesforce took floors 3 through 30 and the 61st floor, so we have the high-rise portion of the building left to lease, with some of the best views in San Francisco.”

Addressing Housing Needs

In addition to offices, the district has a significant affordable housing component: of the 4,400 units of new housing, 1,200 will be permanently affordable. The first project completed in the Transbay Redevelopment Area is Rene Cazenave Apartments, developed by two local nonprofit organizations, Community Housing Partnership and Bridge Housing. The eight-story building—located on Block 11, the site of a former freeway off-ramp—consists of 120 apartments for formerly homeless individuals, supportive services, and ground-floor retail space. It was designed by local firm Leddy Maytum Stacy Architects and completed in early 2014.

Several other multifamily housing projects are underway, both as part of market-rate developments and as standalone developments. Bridge Housing, for example, is also providing 109 units of below-market-rate family units at Transbay Block 9. That multifamily complex on Folsom Street also includes 436 market-rate units created by local developer Avant Housing and Palo Alto–based equity partner Essex Property Trust. The local office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill teamed up with local firm Fougeron Architecture on the design. Completion is expected by early 2019.

“Being walkable to downtown, the financial district, the Embarcadero, and obviously the transit terminal is a huge plus,” says John Eudy, chief investment officer of Essex Property Trust. “Getting in and out of the city by road is very easy, too. We do own some other properties in the South of Market area. They are great, and proximity to the downtown is very good. But this is at the apex of where we think long-term urban dwellers in San Francisco are going to want to be.”

The TJPA anticipates that creation of a pedestrian-oriented environment with easy access to public transit, open space, parks, and a mix of uses will result in property value premiums throughout the district and beyond.

“There is a growing interest on the part of the development community in walkable urban places that have great transit access,” says Libby Seifel, president of local economic consulting firm Seifel Consulting. “A lot of the young people desire that kind of living, and empty nesters are returning to the city and wanting a more walkable and easier lifestyle.” According to a report Seifel Consulting prepared for the TJPA, “Transbay Transit Center: Key Investment in San Francisco’s Future as a World Class City,” the Transbay program is projected to increase the value of private properties located within 0.75 miles (1.2 km) of the transit center by 5 percent, on average—an estimated total of $3.9 billion, representing a $1.2 billion jump in the value of residential property and $2.7 billion in the value of commercial property.

Financing and Completion

Funding for the Transbay Transit Center and the downtown rail extension (DTX) comes from a wide variety of local, regional, state, and federal sources, including revenues from the sale of land parcels, redevelopment bonds, property taxes, sales taxes, transfer taxes, and development impact fees. A $400 million American Recovery and Reinvestment Act grant and a $171 million federal loan through the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act enabled construction of the first phase to begin in 2010.

In January 2015, San Francisco Mayor Edwin Lee signed legislation creating a Mello-Roos Community Facilities District for the Transit Center District Plan area. Under this law, developers seeking to “upzone” in the area—to build taller than the 550-foot (150 m) height limit—are required to pay a tax to fund the additional infrastructure required by higher densities. Of those revenues, 82.6 percent are designated to go to the Transbay project. Some will be used to complete the first phase, but most of this money is earmarked for the second phase. This year, the TJPA also issued a request for proposals for sponsorship opportunities, offering the right to name the Transbay Transit Center and its component facilities, equipment, and services. The authority expects to make its choice by the end of this year.

The first phase is expected to be completed by late 2017, including the new Transbay Transit Center with an above-grade bus level, ground-floor and concourse-level retail space, and foundations for two below-grade levels to service Caltrain and high-speed rail.

It is less certain when Caltrain and high-speed rail service will roll into the terminal. Construction of a high-speed rail line began in Fresno in early 2015, but more funds need to be raised to complete the system. Meanwhile, Lee has proposed an alternative route for the Caltrain extension that would bring it underground through the Mission Bay neighborhood in order to place an additional station near a proposed new waterfront arena for the Golden State Warriors National Basketball Association team.

The Rene Cazenave Apartments development, which occupies the site of a freeway off-ramp demolished after the Loma Prieta earthquake, includes a private landscaped courtyard for residents. The first project completed in the Transbay Redevelopment Area, the development contains 120 apartments for formerly homeless individuals, supportive services, and ground-floor retail space. (©Tim Griffith)

Lee’s idea would hold the potential to mitigate heavy automobile traffic associated with the 18,000-seat arena, but it would require redrawing the already-approved route, thus delaying the extension. “We have an environmentally cleared alignment for the DTX,” says Scott Boule, legislative affairs and community outreach manager for the TJPA. “Having those environmental clearances allows us to pursue significant funding streams that will help us construct the DTX. We’re in the process of lining up those funds. If the route were to be changed, we would have to start that process all over again, which takes many years, and it would delay our ability to raise those revenues.” The city is conducting a study of the alternative route.

Even with the train portion of the project still taking shape, the Transit Center District is already experiencing construction of multiple large-scale office and housing developments. The 1989 earthquake, the influx of tech companies to the city, the region’s growth, and the municipality’s decision to increase density in the district have come together to initiate an unprecedented transformation in a city that has sometimes mourned change.

“Everyone wants to be next to the transit center,” says Ayerdi-Kaplan. “We’ve created a huge boom in the market that would not have happened without the building of the new station. Nineteen towers are under construction in the Transit Center District. From the very beginning, we expected that we would have a certain number of properties and parcels that we would sell for development, but this has far exceeded our expectations.”

Ron Nyren is a freelance architecture and urban planning writer based in the San Francisco Bay area.