The banking sector has provided about half the approximately $3 trillion of outstanding commercial real estate debt, according to Federal Reserve data. However, new Basel III rules released July 2—requiring U.S. banks, savings associations, bank holding companies, and savings and loan holding companies with over $500 million in assets to maintain higher capital levels—may result in allocation of bank capital away from real estate and higher financing costs. As a result, developers may find future projects less attractive.

Introduction of the HVCRE Loan

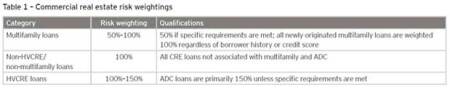

As is the case under the current rules, under Basel III most commercial mortgages are assigned a risk weighting of 100 percent, requiring banks to hold capital equal to 8 percent of the balance of the indebtedness. However, multifamily loans remain eligible for a reduced risk weighting of 50 percent if after one year there is evidence of timely principal and interest payments and if the loan meets specific credit criteria. The big change is the risk weighting for a new category of loans—high-volatility commercial real estate (HVCRE) exposures, defined as “a credit facility that finances or has financed the acquisition, development, or construction (ADC) of real property.” These loans receive a risk weighting of 150 percent, requiring banks to hold 12 percent capital rather than 8 percent, and therefore have received significant attention.

While specific types of loans are exempt from the HVCRE classification, other ADC loans may be exempt if they meet three criteria:

- the loan must have a loan-to-value ratio (LTV) of 80 percent or less;

- the borrower must contribute capital to the project in the form of cash or unencumbered marketable assets of at least 15 percent of the appraised “as complete” value; and

- the borrower’s capital must be contributed before bank funding and remain in the project throughout the life of the project. The life of the project concludes when the credit facility is converted to permanent financing, sold, or repaid in full.

While the exception criteria are aimed at improving bank lending standards, many ADC loans are unlikely to fall into the HVCRE definition because of these exemptions. Most banks provide ADC loans at leverage levels far lower than the 80 percent threshold, and borrowers are typically required to contribute equity to the project before the bank funds the debt.

However, the third exemption focused on borrower equity may be harder to achieve because this test departs from traditional bank credit practice in two important ways:

- Currently, the required equity is typically based on the project’s cost rather than the “as completed” value of the project, and

- banks usually give credit to the current value of developable land as the borrower’s “skin in the game.”

This third exemption may be problematic for a developer who wants to build on land previously invested in and held for the right market circumstances. These borrowers may not only find capital harder to obtain from banks, but also the amount and timing of additional equity will have a direct impact on the project’s feasibility.

Finding construction capital at nontraditional lenders may eliminate the equity issue, but the cost of capital from private equity and other nonbank lenders is typically higher. As such, the equity requirement may hurt development. While there has been limited construction in the United States during the past five years, population growth and other demographic shifts over the next decade will require significant commercial development.

Impact on Liquidity and Cost

A potential outcome of the new rules is that banks will no longer want to be the primary source of ADC capital to the industry. Securitization and other traditional lenders such as life companies are unlikely to fill the gap, resulting in borrowers seeking capital from nontraditional lenders such as private equity funds, which are more expensive. Of course, the banks may want to stay in the ADC business—they have the expertise and infrastructure—but they must charge more for HVCRE loans to retain profitability. Either way, the cost of ADC capital is likely to rise, putting upward pressure on capitalization rates, which drive the value of stabilized properties, and discount rates, which drive the value of new and transitional properties. Accordingly, higher mortgage rates lower both the profitability and asset values of property owners. The resulting lower collateral values would raise LTV ratios and ultimately reduce loan proceeds to real estate borrowers.

Another reason rates may rise on all commercial mortgages is changes to capital requirements relating to mortgage servicing rights (MSRs), the separable asset created when a bank originates a mortgage loan. While the new rules are complex, the bottom line is that if banks have sufficient MSRs, the risk weighting against them can rise as high as 250 percent. This may cause servicing fees to rise, and those fees are embedded in the mortgage interest rate. If more servicing is moved to nonbank servicers, they could take advantage of the situation by raising their fees. Again, whether servicing is done inside or outside the banking system, borrowers could see a permanent change in commercial mortgage pricing.

On the positive side, Basel III could induce banks to provide more capital to the multifamily sector with the lower risk weighting of 50 percent. This would benefit apartment owners by increasing liquidity when it is most needed: the shift from homeownership to rental housing continues, and the Federal Housing Finance Agency has mandated that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac lower their multifamily origination volumes. It should be noted, however, that multifamily ADC loans are treated the same as any other property type. As developers meet continued demand for rental units, their lenders will not benefit from a lower risk weighting until the projects stabilize.

While banks historically have been the largest source of debt capital to the commercial real estate sector— particularly for ADC loans—the result of higher capital requirements for HVCRE loans and MSRs in Basel III will be higher mortgage rates and potentially less capital allocated to commercial real estate. As these changes are implemented, they will collide with an environment of rising interest rates and an increasing demand for development. This loss of liquidity and higher pricing will likely make the business of developing and owning real estate less profitable and curtail construction and real estate transactions.

For a more detailed description of the technical rules, see “Basel III’s implications for commercial real estate” at ey.com.

Joseph Rubin is principal in Transaction Real Estate practice, Stephan Giczewski is a senior manager in Financial Services Risk Management Advisory, and Matt Olsen is a manager in Transaction Real Estate, all with the Ernst & Young.