Cities around the world continue to struggle with the danger and damage of flooding. A 2013 World Bank study estimates that global flood losses average about $6 billion per year. Population and economic growth in vulnerable regions are predicted to increase annual flood losses to $52 billion by 2050. Add in climate change, and annual losses could top $1 trillion. The rising sea levels and increasingly intense rainfalls predicted by climate-change scientists will make the struggle to deal with flood risk more difficult—and more pressing.

“Responsible real estate development and investment requires understanding more than just the risk of flooding. It requires estimating the severity of the flooding and the damage it is likely to cause,” says John McIlwain, ULI senior fellow and a chair of the 2013 ULI Advisory Services panel that produced the report After Sandy: Advancing Strategies for Long-Term Resilience and Adaptability. Understanding flood risk, moreover, means understanding flood-risk mapping.

During Hurricane Sandy in 2012, the area flooded in New York City’s Brooklyn and Queens boroughs was almost double the area defined by official maps as special flood hazard areas (SFHAs). In the city as a whole, the water rose above the flood elevations indicated on risk maps in more than half the areas that were flooded. The challenge ahead for flood-risk management through mapping is to figure out the factors contributing to the discrepancy between mapped risk areas and damage—the part played by insufficient data and models and the part played by the effects of climate change—while acknowledging that the discrepancy could also be the consequence of the societal gamble inherent in any flood-risk-mapping effort.

Better data are becoming more widely and publicly available. Remote sensing via light detection and ranging (LIDAR) can create precise three-dimensional maps of shorelines and land elevations, greatly increasing the accuracy of flood-risk mapping. In the United States, standards require maps to be updated on a five-year cycle, and a 2014 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) notes that significant strides have been made to modernize flood maps in recent years. Federal appropriations for this effort, however, are declining: from $325 million in 2009, the map modernization project has declined to only $208 million appropriated by Congress in 2013.

Climate change, however, threatens to undo the increased certainty promised by better data. Flood-risk mapping has traditionally been backward looking, built on the assumption that the future will look much like the past. In the United States, laws in 2012 and 2014 began the process of trying to incorporate climate science into the federal flood-risk maps that underpin the flood insurance program and floodplain management. In the European Union, the most recent directive requires that member states regularly update their flood-risk maps, incorporating new information about climate change.

Not only is the science behind future flood-risk mapping difficult and complex, but it also is likely to be in tension with politics. Official studies in the neighboring states of Virginia and North Carolina illustrate the challenges ahead: whereas officials in Virginia are looking at scenarios 100 years into the future and analyzing the impact of sea levels that rise up to five feet (1.5 m), North Carolina officials confined their study to 30 years, which limited the sea-level increase to a less-formidable eight inches (20 cm).

Understanding Flood Risk

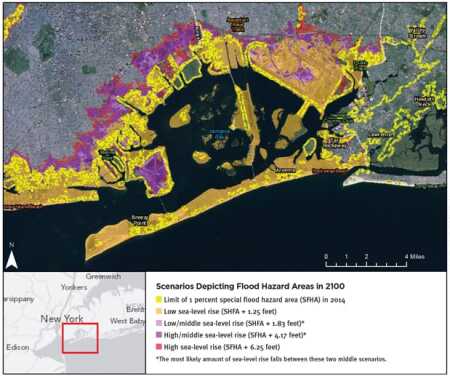

The map, from the U.S. Global Change Research Program, depicts flood hazard areas in 2100 based on regional scenarios of sea-level rise developed by the New York Panel on Climate Change. It was created using the Sea Level Rise Tool for Sandy Recovery (www.globalchange.gov/browse/sea-level-rise-tool-sandy-recovery). Additional mapping tools examining American coastal regions are available from Digital Coast (www.csc.noaa.gov/digitalcoast/), a project of NOAA’s Coastal Services Center. ULI is a member of the Digital Coast Partnership.

When managing floods, government policy starts by deciding which flood risks to map.

For example, the European Union requires member states to map the 1 percent annual flood risk—areas that have a 1 percent chance of flooding in a given year. The U.K. Environment Agency maps areas of 1 percent annual risk for river flooding, but uses a less risk-tolerant level, 0.5 percent (one out of 200), for areas subject to flooding by the sea. The United Kingdom defines extreme flooding as flooding with a one out of 1,000 chance (0.1 percent) of occurring within a year. Maps of these flood-risk areas are available to property owners and insurance companies.

The Netherlands, where millions of people reside below sea level, builds flood defenses to standards as stringent as limiting the risk of failure in any given year to one in 10,000 (0.01 percent).

The United States uses the 1 percent annual risk as the base for its National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) and defines extreme flooding as 0.2 percent (one out of 500) annual risk. Flood insurance studies provided to local communities also indicate areas of 10 percent and 2 percent annual risks. The government’s accompanying floodplain management training gives examples of how to use the maps for land use planning, infrastructure development, and facility siting: the 10 percent flood risk is useful for locating septic systems, the 2 percent risk can inform decisions on bridges and culverts, and the 0.2 percent indication provides guidance on areas to avoid when locating critical facilities such as hospitals.

The different percentages of annual risk translate to different lines of probability on a map. According to established conventions, the lines indicate the probability, over the course of one year, of normally dry land being flooded at least once.

The land between the river or shore and the mapped risk line has the designated percentage or greater chance of flooding each year.

(The 10 percent, 2 percent, 1 percent, and 0.2 percent probabilities correspond, respectively, to ten-year, 50-year, 100-year, and 500-year flood risks. The tradition of referring to flood probabilities in terms of a “number-year” has led to significant confusion. The proper interpretation of this naming convention is not that a 100-year flood occurs once every 100 years, but that the chances are one in 100 that a flood will happen each year.)

As flood-risk mapping gets more sophisticated, the range of the flooded area is accompanied by flood elevation—the projected height of the floodwaters. Flood-risk analysis may also include the expected speed of the water flow.

Studies of flood elevations and velocity also inform building codes, providing guidance on how high to elevate the lowest floor and how strong support structures or flood-proofing need to be.

Flood-risk mapping for insurance and land use planning is based on historical and modeled averages. But as Maria Honeycutt, coastal hazard specialist for the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), explains, “storms are all different. No one storm is going to produce the 1 percent flood-risk area. The area that will get flooded is different every time.” Moreover, she continues, “floodplains change; the map is not static. In reality, nothing about this is static.”

In addition, other types of flood mapping may be relevant to sound development and investment decisions.

Doug Marcy, a colleague of Honeycutt’s at NOAA, specializes in building data-based tools designed to translate the science into forms useful for making decisions. He points to two other types of useful flood mapping: evacuation planning and localized flooding.

“Evacuation planning uses worst-case-scenario planning,” he explains. “It goes way beyond the 1 percent risk.” These mapping efforts are not based on the likelihood of the monster hurricane heading to shore or the levee being in danger of breaching, but what to do when such rare events are actually happening.

For more localized and less serious flooding, including urban flooding, weather forecasters may work with city officials to map these major and minor events in order to issue local warnings, close roads, or analyze the impact of the high water on businesses or public facilities.

Mapping and Insurance in the United States

The federal government took the lead on flood-risk mapping in the United States as part of the NFIP, which Congress launched in 1968 after decades of flood-related disasters that burdened the federal treasury, compounded by a lack of viable alternatives in the private insurance market. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) administers the program in partnership with nearly 90 private insurance companies that sell the policies.

Insurance policies are only available for purchase in communities that agree to participate in the NFIP’s floodplain management program, which sets minimum standards for land use planning, subdivision ordinances, and building codes.

For the federal government, the NFIP was—and continues to be—seen as a way to engage property owners and communities in risk-reduction activities, as well as to create a mechanism to share financial risk. Flood-risk mapping underpins the entire program: it informs the insurance rates, the communities identified as being at risk, and floodplain management standards.

The NFIP defines an SFHA as “the area covered by floodwaters of the base flood”—the event having a “1 percent chance of being equaled or exceeded in any given year.” The height of the water during the 1 percent flood is the base flood elevation.

More than 21,000 communities, or about 90 percent of at-risk communities, participate in the NFIP. Homeowners, renters, commercial property owners, and businesses in participating communities can buy flood insurance through the NFIP, with premiums based on risk categories. Purchasing insurance is voluntary, though property owners in SFHAs must have flood insurance in order to be compliant with the rules for mortgage from a federally regulated or federally insured lender.

Participating communities must adopt and enforce flood-management regulations. Requirements include administering a development permitting process that regulates the siting and construction of buildings and activities such as filling, dredging, paving, or grading. In general, new development must not increase the flood hazard of other properties, and new buildings must be protected from the base flood, as must buildings that have been “substantially improved,” including repairs after significant damage. New or improved infrastructure must also be designed to avoid or minimize flood damage.

Through its Community Rating System, the NFIP provides incentives for communities to go beyond the required minimum standards. Individuals are eligible for insurance discounts if their community engages in activities chosen from a menu that includes more restrictive flood-risk mapping, floodplains preserved as open space, high-risk areas zoned for low-density development only, or relocation of flood-prone buildings to higher ground. A 2014 GAO report found, however, that only about 1,200 communities participate in this incentive program.

FEMA calls the map that defines an SFHA and its flood elevations a “flood insurance rate map.” In the program’s early decades, flood-risk maps indicated only flood areas, not elevations. Fees on policies, as well as other federal funding, have paid for rounds of map modernization, including the transition from paper to digital maps. Incorporation of flood elevations and wave heights for coastal areas has been an ongoing priority, according to the GAO. FEMA also updates maps using data drawn from other agencies and requires owners of large development projects to submit flood-elevation studies where they are not yet available.

Updating a rate map is a public process. FEMA consults the community throughout the process, including holding community coordination meetings, both to educate the community about revisions and because FEMA recognizes that local knowledge of building and landscape changes is crucial to accurate mapping. Property owners have the right to appeal new designations to FEMA. Although the map updates can lead to property owners being assigned higher and lower risks—and therefore higher or lower insurance premiums—owners deemed at higher risk have the greatest incentive to appeal. Potentially at stake for property owners are thousands of dollars per year in insurance premiums or the need to do expensive building upgrades. The FEMA appeals process requires that appeals are to be decided based only on scientific or technical information about flood risks; the economic consequences of a higher-risk designation are not among the decision-making criteria.

In the end, it is important to remember that there is nothing magically safe about being outside the line indicating 1 percent annual risk. According to FEMA’s FloodSmart.gov website, “People outside of mapped high-risk flood areas file nearly 25 percent of all NFIP flood insurance claims.”

With climate change, as sea-level rises accelerate and heavy rainfall events become more frequent, the lines on the maps defining high-risk areas march inland, while the height of the floodwater in high-risk areas climbs higher. But how far inland? And how high will the water be? And how soon will it happen?

Bottom line: that official flood-risk map, which today indicates that a development project or investment is just outside a high-risk area or elevated just high enough to avoid damage, is likely to say something very different in the not-so-distant future.

Sarah Jo Peterson is the senior director, policy, at ULI.