In early December, ULI members gathered virtually to discuss climate risk and real estate at the second annual Resilience Summit. The event’s agenda focused on how real estate and land use professionals can prepare for and adapt to the impacts of climate change, and where leadership could help shape better outcomes for the future.

The speakers participating in the summit agreed that climate change is leading to increasingly costly financial and human impacts, some of which are already apparent and others of which could occur in the near future due to the increased occurrence of climate events such as wildfires and hurricanes. There also are shifts occurring in the insurance and financial industries, and government disaster recovery policies. Many of the speakers also emphasized that the industry increasingly has the tools and approaches needed to address climate risk, but leadership is needed for broader application and recognition of the gravity of the situation.

Keynote speaker Katharine Wilkinson, principal writer and editor-in-chief for Project Drawdown and co-editor of the new anthology All We Can Save, began the day with this call for leadership. “The climate crisis is a leadership crisis,” she said. “To transform society this decade, it is going to take transformational leadership.”

Wilkinson initially focused on the solutions already available to the real estate industry to reduce emissions. She introduced the Drawdown framework, which outlines methods to reach the point in the future when greenhouse gases stop climbing and begin to decline. The framework looks at both sources of emissions, and syncs which uplift nature’s carbon cycle. “It is critical to understand all of these solutions as a system, in some ways an ecosystem,” she explained.

Project Drawdown has estimated that if roughly $22.5 trillion were invested to meet a peak drawdown by 2060, there could be a total cost savings of roughly $95 trillion. Similarly, a more ambitious goal to meet drawdown by the mid-2040s could yield initial costs of roughly $28.4 trillion, with the potential cost savings of over $145.5 trillion. “There is also a really compelling financial story to tell,” Wilkinson said. “There are sizable but very doable costs to implement solutions, [but there are also] significant savings over time. It is critical to understand all of these solutions as a system, in some ways an ecosystem, all of [the proposed solutions] are needed and all of them are connected.”

Conversation then moved to the topic of cities and climate leadership, with a panel including the chief resilience officers from Oakland, California (Alexandria McBride), and Charleston, South Carolina (Mark Wilbur). Moderated by Laurian Farrell, North America director for the Resilient Cities Network, the discussion focused on how leaders in city government and real estate can work together to be more prepared for climate events and long-term changes such as sea-level rise. The speakers all agreed that equity, addressing economic opportunity, availability of housing, and access to open space are central to the discussion. Cities that are not equitable will not be able to recover from disruption from climate events or shocks, and will constantly be in “recovery mode.”

“I implore all in the real estate and land use industries to not think about this as just city leadership, but how you can collaborate with public-sector leadership because resilience is something that cities cannot do alone,” said Farrell. “It’s going to take all hands on deck to get this job done.” McBride and Wilbur shared examples of their work advancing climate resilience through city policy, planning, and infrastructure with a focus on how they have engaged the real estate sector.

Wilbur focused on the flood risk, which he described as our “number-one most pressing challenge in Charleston. Prior to 2015, the city was treating this as something they can build their way out of,” he noted. “However, we quickly realized that this is a multifaceted problem that needed to be dealt with on multiple fronts.” The city strives for new development to be “high, dry, and connected,” recognizing that flood-ready developments can only be effective if surrounding infrastructure also remains passable during climate events.

McBride focused on planning processes in Oakland, including the recent release of the city’s Equitable Climate Acton Plan and the EcoBlock program. Supported with a $6.5 million grant from the California Energy Commission, the EcoBlock project strove for net-zero and low-water-use designs using a community financing model. McBride also introduced the “Better Neighborhoods, Same Neighborhoods” initiative, in which the city partnered with community-based organizations in Oakland over two years, designing strategies for community engagement, workforce development, displacement avoidance, and climate resilience. The project has led to proposals for increased affordable housing, a 1.2-mile (1.9 km) greenway, new workforce development training programs, and investments leading to the reduction of 8,700 metric tons of carbon dioxide.

The afternoon’s programming focused on climate risk and real estate, highlighting the work of investor David Burt, who spoke during a fireside chat with ULI member leader Lynn Jerath. Burt runs an advisory firm, Delta Terra, which is an investment research and consulting firm, which measures climate risk exposure and makes investment decisions accordingly. Burt was featured in The Big Short by Michael Lewis for his huge short bet on subprime mortgages in 2008, and he has described climate change as the Big Short of today’s economy. “I created Delta Terra because I believe that climate risk and its mispricing have created a similarly large value bubble [to the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis] that will significantly impact real estate investment portfolios when it breaks down,” said Burt. “Lenders are essentially making the same mistake today [as in the 2008 financial crisis] by qualifying borrowers’ ability to pay based on an assumption that their insurance costs will stay constant in the future.”

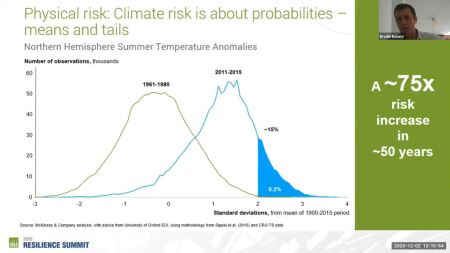

The summit’s main-stage programming concluded with a panel on climate risk and real estate. In the session “Climate Risk and Real Estate: Industry Innovation and Emerging Practices,” moderator Brodie Boland (associate partner, McKinsey & Company) and panelists Mona Benisi (global head of sustainability real assets, Morgan Stanley Investment Management) and Daryl Fairweather (chief economist, Redfin) discussed how climate risk data is influencing investor and homeowner decision-making, especially at a market level.

Boland emphasized that “physical risk and climate change are already here” and that “one of the important things from the perspective of a real estate investor, owner, or operator is” the increase in extreme weather events. Investors and developers are increasingly conducting physical risk assessments of their assets and portfolios, but they say that navigating the growing climate analytics market is a challenge.

“All of the [climate analytics] providers use scientifically sound climate models, but the difference is the interpretation of the models and that the tools are all asking slightly different questions. You have to take the time to go through the process and understand this,” said Benisi. She recommended that Resilience Summit attendees consider the type of company, risk score delivery, type of included risks, measurement of direct or indirect impacts, as well as climate change scenarios and time horizons when considering which data providers to select.

In contrast, homeowners do not typically have access to sophisticated climate analytics. However, Fairweather said that “homebuyers are starting to think about what climate risks might be in the metro areas they’re moving to.”

To learn more about the event and other opportunities with the Urban Resilience program, visit the ULI Urban Resilience website or express interest in participating as a member via Navigator.