The cascading effects of climate change demand a new approach to how buildings are developed and managed.

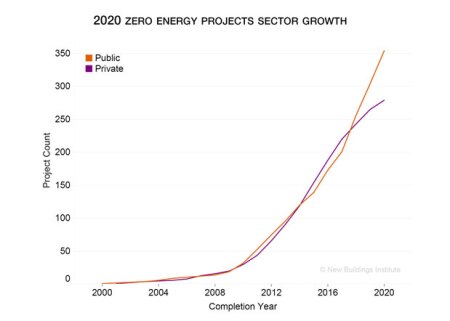

In the past two years, the number of net-zero-energy (NZE) commercial buildings in the United States has increased by 42 percent. While that is high growth, representing 62 million square feet of space, the overall number—roughly 700 U.S. properties achieving or striving for net zero—is still low. These highly efficient buildings consume only as much energy as can be produced on site through clean, renewable resources, which in most cases is solar power. The definition, though, has expanded to include off-site renewables, recognizing that for some projects on-site solar installations just are not feasible.

As part of the first Net Zero Buildings Week this week, ULI, the New Buildings Institute (NBI), and other organizations focused on improving the built environment are calling on partners and members to share their thought leadership on net zero. Throughout the week, more than 80 organizations will be sharing guides, tools, case studies, reports, and other resources to put buildings on the path to net zero. The effort aims to reach thousands of influential architects, engineers, owners, developers, and operators, with an emphasis on those who are not familiar with or have not bought into the growing net zero practice.

Bridging Net Zero from Energy to Carbon

As the increasingly severe impacts of climate change—wildfires, and hurricanes and resultant flooding—become more prevalent, cities and states are looking at a number of strategies to mitigate planet-warming carbon impacts of emissions. Buildings represent roughly 40 percent of those emissions.

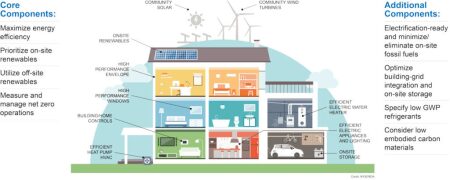

While zero-energy buildings are not necessarily carbon neutral, the two performance goals are closely connected. Both require core components of energy efficiency, on-site renewables (and off-site resources when necessary), as well as the ongoing management of building operations.

Carbon-neutral buildings require renewable energy overgeneration to offset any emissions resulting from power production or on-site combustion of natural gas or other fossil fuels. Calculators such as eGrid help building owners understand what is required to offset carbon emissions for a building. There are additional components that lower the carbon emissions in the first place—electrification of end uses such as space and water heating, technologies that help building systems work in concert with the electricity grid, and finally, considerations regarding embodied carbon. As the carbon footprint of operations is ratcheted down, embodied carbon, which currently accounts for 11 percent of carbon from the built environment, will become a larger share of the problem.

Benefits of Net Zero Go beyond Energy

Ownership trends show the public and private sectors pursuing net zero at about the same pace until the couple of years ago, when climate-action policy drove steeper growth in public buildings. Early adopters such as Morgan Creek Ventures in Boulder, Colorado, have formed a compelling business case for zero-energy/lower-carbon developments that incorporate a number of benefits. According to analysis from CBRE of employee productivity, even a modest level of increased productivity, on the order of 3 percent, will cover the cost of a tenant’s base rent at Morgan Creek Venture’s Boulder Commons project.

“While not without its challenges, as with any leading-edge project, we have delivered market rate returns, a solar wall/roof, and rental rates competitive with comparable class A stock in our immediate surroundings,” says company founder Andy Bush. Other benefits reported for net-zero developments include the ability to charge higher rents, faster lease-up rates, and better tenant retention.

With a growing amount of power generation distributed on NZE building rooftops and in neighborhoods, developers are starting to understand the opportunities for buildings to contribute to the power supply mix. Wasatch Group installed storage batteries in each of its 600 units at the firm’s net-zero Soleil Lofts project in Herriman, Utah. By generating power during off-peak times when energy is cheap and selling it back when demand and prices are higher, the project offers local utility Rocky Mountain Power a ready power resource and earns money for the developer, according to Wasatch Group.

The “virtual power plant” provides “an income stream and makes this a more attractive property to rent,” says Ryan Peterson, president of Wasatch Guaranty Capital, the firm’s real estate and investment unit. “One of the reasons we’re looking at renewables and solar is that it reduces operating expenses and increases cash flow—a big deal to real estate owners.”

What’s Next

The science is clear that the next 10 years are critical for addressing climate change. The good news is that between the building and energy industries alone, significant knowledge and resources exist for practitioners to get started. ULI Learning recently kicked off a five-part education series with Sharp Development founder Kevin Bates taking participants through the details of what it means to build to net zero, including design, operations, finance, and non-energy benefits such as wellness. The course, Net Zero Real Estate: Renovating and Building for Profitability, began March 22 and is still open for late registration.

STACEY HOBART is communications director for the New Buildings Institute, a nonprofit organization working to improve the energy performance of commercial buildings. MARTA SCHANTZ is senior vice president of ULI Greenprint, a worldwide alliance of leading real estate owners, investors, and strategic partners committed to improving the environmental performance of the global real estate industry.