How do five diverse cities spread across two counties act as one, especially when it comes to raising and spending money?

Twenty minutes south of Chicago’s central Loop district, Lake Michigan’s lakeshore and sandy beaches continue along a string of small cities in Northwest Indiana. Hammond, Whiting, East Chicago, Gary, and Portage—cities with their own long, unique histories—have united behind a coordinated lakeshore revitalization strategy built on parks and greenways. Only six years into the strategy, new housing and business activity are beginning to take advantage of the investments in the public realm.

Northwest Indiana is emerging as an important case study of how to use a regional vision to transform conditions on the ground. Such efforts are always built on a strong foundation of collaboration—in this case among the state government, five municipalities, two counties, a new regional development authority, and numerous private sector actors. The Northwest Indiana model also features clearly defined areas of responsibility that provide incentives to get things done.

The Marquette Plan, adopted in 2005, promotes the region’s vision for lakeshore reinvestment. Organized around a call for creating a livable lakefront, the plan includes frameworks for industry, roads and rail, greenways and multiuse trails, and community investment in parks and lakefront development. However, the lakeshore plan was the culmination of decades of leadership and leaders who understood the opportunities deriving from being located deep inside what is usually thought of as the American Rustbelt.

Deindustrialization—the bogeyman of the Great Lakes—is not quite the right word for the transformation underway in Northwest Indiana. Steel giants U.S. Steel and ArcelorMittal still occupy their historic lakefront works, and BP runs a major petroleum refinery in Whiting. The industrial restructuring that severely contracted the area’s workforce and its traditional blue-collar neighborhoods was largely accomplished by the 1990s. Manufacturing, from small shops to international corporations, will continue to be an important part of the area’s economy.

Restructuring also shrank industry’s environmental footprint, and in the 1980s area leaders, including longtime U.S. Representative Pete Visclosky, began to recognize the valuable asset in their midst. “Lake Michigan and the entire Great Lakes represent a natural and economic resource unique in the world,” Visclosky says of the momentum for success that became the Marquette Plan. “If we responsibly recapture and preserve the lakeshore for open public use, the potential for economic development and job creation is limitless in the adjoining lands and communities.”

The communities responded with what turned out to be a key component of the lakeshore reinvestment strategy: instead of each going it alone, they decided to treat Lake Michigan and the area’s natural amenities as a collective, regional asset. As the memorandum of understanding that led to the Marquette Plan states, they agreed “to act as one voice in decision-making and fundraising.”

How do five diverse cities spread across two counties do that, especially when it comes to raising and spending money? Enter the Northwest Indiana Regional Development Authority (RDA). Local leaders rallied around the new authority, created in 2005 with bipartisan support in the state legislature. Designed to be a catalyst for change working in partnership with the cities, the RDA has a board made up of experienced people appointed by the governor and local governments.

The RDA’s enabling legislation focused on regional assets—Lake Michigan and the area’s connectivity to Chicago—and directed the authority to target for investment the planned lakeshore greenways and transportation: the Gary/Chicago International Airport, commuter rail, and the regional bus system.

Combining state and local funding sources provides the RDA with $27.5 million in annual revenues. Gary, East Chicago, Hammond, and Lake and Porter counties have each committed to contribute $3.5 million annually. Casino revenues make up the bulk of the funding from most of the jurisdictions.

Funding from the state comes from the 2006 Major Moves legislation and the lease of the Indiana Toll Road (Interstate 80/90 through northern Indiana) to Statewide Mobility Partners LLC, a limited liability company partnership between the Spanish firm Cintra and the Australian Macquarie Infrastructure Group. The 75-year toll road lease generated $3.8 billion. Although privatizing toll roads, especially in deals with international corporations, is controversial in other states, for Indiana and Governor Mitch Daniel’s administration, revenue from the lease became a flexible source of funds for other projects. After committing an initial $20 million for the RDA, Indiana is committed to contributing another $10 million annually through 2015.

By 2006, Northwest Indiana had the three pieces in place to take a regional approach to development: a vision to guide the investment, an institution well positioned to make the investments, and commitments for funding. Since then, the RDA has returned over $206 million to the region through grants to specific projects and has helped focus additional local, state, federal, and private sector funding on investments totaling nearly $512 million.

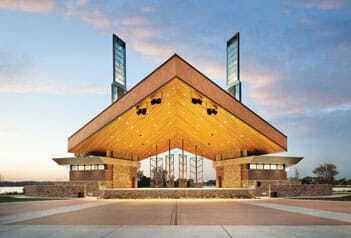

The RDA and the communities began their effort to promote shoreline development by improving the lakefront parks and connecting them with multiuse trails. By starting with the existing parks, the effort supports an orientation toward results; more complex shoreline projects that address the legacy industrial infrastructure, which often is still active, await later phases. Park improvements target natural areas, including improved water quality, and recreation for local residents such as playing fields and fishing piers. They also concentrate on regional draws such as the historic pavilion in Gary’s Marquette Park, long a popular site for weddings, and Hammond’s new state-of-the-art music pavilion and amphitheater accommodating 15,000.

With the park revitalization projects well underway across the region, the communities and the RDA are focusing on the corridors and gateways that connect the parks with neighboring residential and business districts. RDA executive director Bill Hanna views the park improvements as three-pronged investments: they improve natural areas, the recreation experience, and the economic development climate. Of the park investments, Hanna observes, “The amenity value is becoming clear. We’re starting to see an impact on development and revitalization in the nearby neighborhoods.”

East Chicago’s North Harbor district is one of the areas receiving a boost from the region’s lakeshore reinvestment strategy. The city has long recognized the area’s potential, welcoming an Urban Land Institute advisory services panel in 2000 to examine the district’s traditional downtown and nearby residential neighborhoods. Today’s North Harbor Revitalization Initiative advances the city’s vision for a mixed-income, pedestrian-oriented community with access to a revitalized Main Street district and to the amenities of the Lake Michigan lakefront.

| Hammond’s new state-of-the-art music pavilion and amphitheater, |

The relocation of an old water filtration plant provides a relatively straightforward example of the partnership between local communities and the RDA. East Chicago successfully leveraged state and RDA funding for the $56 million project that included construction of a new plant and demolition of the old one. The project frees up ten acres (4 ha) of developable land near the East Chicago Marina that is now being planned for catalytic redevelopment.

Nearer the center of the neighborhood, the North Harbor Revitalization Initiative is wrapping the intersection of Main and Broadway streets with revitalized commercial buildings and new townhouses. The Main Street downtown still has the services and destinations that make up the heart of the community—small businesses and restaurants, a post office, a bank, a clinic, an elementary school, a community center, and two parks.

The city has used its own funds, as well as directed federal dollars and attracted private donations, to reconstruct Nunez Park and Callahan Park, build a new police substation, and convert a former library into a performing arts center. Streetscapes, sewers, and water lines are being upgraded in the key retail corridor, and the effort also includes aligning city zoning and building codes to encourage pedestrian-oriented, mixed-use development along the corridors and strengthening homeownership in the surrounding neighborhoods.

Since the initiative began, vacant storefronts are reopening with new businesses. At the corner of Main and Broadway, a new 6,000-square-foot (560-sq-m) community retail building features community meeting space above restaurant and office space on the first floor. The new housing in the adjacent neighborhoods targets the demand for high-quality rental product in order to attract working families back to the neighborhood. In the past year, the Community Builders Inc., a national nonprofit focused on mixed-income neighborhood revitalization, experienced a strong lease-up for its first 75 townhouses in the area, and an additional 50 units are to be completed and offered for lease early this summer. A 56-unit apartment development for seniors is also in predevelopment.

With the Main Street district revitalization underway, East Chicago, with the support of the RDA, is now focused on building a market for homebuyers by capitalizing on the North Harbor’s traditional neighborhood amenities and its lakefront community potential. Financial incentives for first-time homebuyers are also available.

For Northwest Indiana, the hardships and challenges that still reverberate decades later from the economic shocks of industrial restructuring are real. But if all that people see are rusting railroad trestles and sagging neighborhoods, they are missing the complete picture of the legacies of the region’s past and the work underway to build its future. Nor should observers underestimate the challenges inherent in regional approaches to economic development. Effectiveness requires policies designed to build a foundation of trust and quickly establish a track record of success to keep such diverse communities at the table.

ULI Chicago, impressed with Northwest Indiana’s efforts, recently asked whether the region was ready to expand its approach to infrastructure, industry, and nature with new partners across the state border in Illinois. Chicago’s south shore communities, with similar legacies and ambitions, could make willing allies in the work that still lies ahead.

Of course, not everyone is going to have Lake Michigan beaches or toll road lease funds, but as Hanna observes, “every community in the country can look at their own assets and ask, ‘Are they performing?’ and follow up with ‘How can they perform better?’”

See ULI Chicago’s study of the Northwest Indiana/Chicago border region, “The Lakeshore Industrial Heritage Corridor: Infrastructure’s Role in Revitalizing Lake Michigan’s South Shore Communities.”