On the banks of the Lower Duwamish River, the neighborhoods seem far removed from the high-tech campuses and coffee-shop culture that have transformed Seattle. Much of the area is zoned industrial; Boeing built bombers in a factory along the Duwamish during World War II. The residential neighborhoods are filled primarily with people from a mix of low-income minority groups, who are often unable to afford homes in the booming parts of the city. To top it off, the waterway is badly polluted with toxins and industrial waste and was identified in 2001 as a Superfund site by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Amid this swirl of social, economic, and cultural issues, another threat looms: rising sea levels. Destructive floods that happen on an annual basis now will occur monthly by 2035 and daily by 2060, according to city of Seattle projections. Of all the factors facing the area, “the largest impact will be sea-level rise,” says Steve Lee, senior policy adviser for Seattle’s mayor, Ed Murray. “It has been a significant issue.”

In 2015, ULI’s Advisory Services program convened a ULI resilience panel to study the issues facing the Lower Duwamish. The multidisciplinary group, chaired by James DeFrancia, president of Lowe Enterprises Community Development, was charged with recommending strategies for handling increased flooding caused by sea-level rise and enhancing the communities’ resilience. After meeting with local leaders and studying the area, the panel formulated a wide range of specific recommendations.

Two years later, a cleanup of the river continues and there is renewed interest in addressing the community issues. Last year, the city formed a new cross-departmental team to focus on the region. But progress has been slow as the communities wrestle with an array of economic, environmental, and political factors—many of the same problems affecting at-risk communities around the United States.

The ULI study was “really a good wake-up call,” says Samuel Farrazaino, founder of Equinox Development, a local company dedicated to creating space for artists. “My hope is that it is not just a report that sits on the shelf.”

Communities Apart

The Duwamish, a five-mile-long (8 km) manmade waterway, separates two very different communities—South Park and Georgetown—with a total of about 5,200 residents. On one bank, Georgetown, one of the oldest neighborhoods in the city, is largely industrial, with a mix of warehouses and factories converted into spaces for artists and restaurants. Across the river, South Park is primarily residential, with a large, working-class Latino population. The neighborhood is bordered by steep bluffs that separate it from west Seattle.

“It’s a very diverse area,” DeFrancia says today. “Such diversity inherently provokes challenges, as what works for industrial does not always work for residential.”

While Seattle is famous for its rain, most wet days are marked by a light rain, not a deluge. It might rain 150 days in a year, but the average annual rainfall is only about 38 inches (97 cm), far less than what falls on some cities in Texas and Florida, for example. The primary flooding risk along the Duwamish comes from high tides, which make low-lying South Park one of the most vulnerable areas in Seattle. “The area is prone to flooding due to backups in the drainage system when there is a combination of heavy rain and high tide,” according to a city of Seattle report.

Floods close roads and swamp riverfront land on a regular basis. “Water rises out of storm drains at high tide, and even more dramatically when there are storms,” DeFrancia says. “Flooding due to rising water levels is already happening.”

Geography works against the area, which is isolated in many ways. It is difficult to get in and out of the communities, which are in danger of getting cut off from the rest of the city in an emergency. But there are larger implications—residents are removed from health and emergency services, as well as from good grocery stores. “Neighborhoods of South Park and Georgetown have limited retail food access, compounded by limited transportation services,” a 2012 study by the city’s Office of Sustainability and Environment noted.

As the ULI resilience panel started interviewing members of the community and examining the issues, the complexities facing the area became clear, panelists say. There was an obvious tension between the residential goals and industrial interests. The flatlands of the Duwamish represent one of the few industrial zones in the city, and there is reluctance to see that disappear.

At the same time, real concern exists about the future of the residential communities. Any move toward gentrification might force out the existing citizens, who are already finding it difficult to afford housing.

“The thing that struck me was the deep commitment all the people had to the community,” says panel member Molly McCabe, founder of HaydenTanner, a real estate consultancy focused on sustainability and energy efficiency. “They wanted to retain the character.”

The focus of the panel’s discussion “evolved,” said panelist Josh Ellis, vice president of the Metropolitan Planning Council, a Chicago-based nonprofit organization. As they talked to more people from the community, it became clear that transportation, food, health, and housing issues were intertwined. “The potential for flooding was on their minds, but it was like tenth on the list,” he said. “It was the observation of the group that they should absolutely be planning for eventualities, but they shouldn’t forget the day-to-day resilience.”

[infogram id="identified_resilience_needs_within_the_duwamish_complex” prefix="6ps” format="interactive” title="Identified Resilience Needs within the Duwamish Complex”]

Practical Recommendations

The panel’s core recommendations ranged from the practical—improve stormwater drainage and raise the level of roads—to fundamental shifts in land uses, encouraging infill light industrial, “maker spaces,” and affordable housing to preserve the communities’ character. The panel identified 12 “impact districts” with different characteristics requiring different strategies for confronting floods, ranging from “locks and hardened bulkheads to riverside parks and berms, bioswales, and rain barrels.”

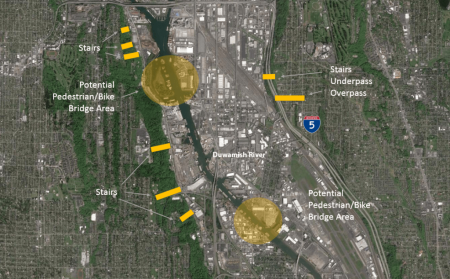

The study also called for a review and update of zoning codes and increased transportation options, including bike paths, water taxis, and more transit stops “to increase connectivity and resilience.” On a fundamental level, the panel noticed there was no staircase for South Park residents to walk up the steep bluffs bordering the community, cutting off access to the resources of west Seattle.

But the report also addressed the big-picture issues facing the community. The team recommended that a collaborative effort be created to go beyond current efforts to form a holistic strategy focused on South Park and Georgetown, with an emphasis on community participation. And land banking was identified as a way to secure parcels for future development for community and recreational sites.

But the topic that prompted the most discussion was a recommendation to create an “urban resiliency fund.” Money for the fund could be generated by allowing increased commercial and residential development in the fast-growing “SoDo” district, home to the headquarters of Starbucks and to Safeco Field, the stadium for Major League Baseball’s Seattle Mariners.

[infogram id="study_area_land_uses” prefix="ZyM” format="interactive” title="Study Area Land Uses”]

While there may be restrictions on tax increment funding, some form of “community revitalization funding” leveraging new development seemed like the logical approach to pay for the badly needed resilience programs, the report concluded. “It’s clear where the [development] market wants to go,” Ellis says. “Why not capture the value and create a fund to pay for [the resilience projects]?”

The panel felt an obligation to figure out some way for the communities to overcome the lack of local financial resources, DeFrancia says. “Funding is always the critical issue, and there are many competing interests in government,” he says. “It is easy to say, ‘Do thus-and-such.’ But absent a funding recommendation, that usually leads to inaction.”

Anything resembling tax increment funding would be difficult to approve under state law, notes Janet Shull, senior planner with the city of Seattle. But she was still intrigued by the panel’s idea of finding a creative funding solution. “What I thought was interesting about the concept was the ability to allow greater development in the local area and take the resources to reinvigorate some neighborhoods,” she says.

The panel has identified potential locations for bridges, walkways, and other paths. The specific locations are subject to a more comprehensive study and survey of the area. For example, locations of the pedestrian bridges focus on increasing connectivity between Herring’s House Park and the Federal Center site. Any additional pedestrian bridge must accommodate river traffic on the Duwamish.

City Response

More than anything, city officials say the ULI effort brought together the diverse interests in the community and served as a catalyst to begin focused action along the Duwamish.

“What helped for us was to come in and take a fresh look,” says Lee. The multidisciplinary approach was particularly helpful, he says. “I found the experience sparked all our thinking. We saw some opportunities we didn’t see before.”

In the wake of the report, the city formed an interdepartmental team to address the area, “a coordinated effort that was kicked off by the ULI discussion,” Lee says. The new Duwamish Valley Action Team has been charged with going through the myriad reports and community input, including the ULI report, and targeting areas for action. “They are really focusing on delivering projects in the community rather than spinning out another planning effort,” says Tracy Morgenstern, a policy adviser in the city’s Office of Sustainability and Environment.

In 2016, the city hired Alberto Rodriguez, who was working with a community-based nonprofit group, the Duwamish River Cleanup Coalition, to serve as cochair of the newly formed action team. The group’s initial focus is to do a better job of responding to neighborhood concerns, he says. “I think the voices [in the community] haven’t been heard historically,” Rodriguez says. “We are trying to focus on building trust by developing responsiveness and taking action.”

The team is focused on identifying capital projects to address the most pressing concerns, such as a tree canopy program and working with community groups on park development, he says. Seattle Public Utilities and the Seattle Department of Transportation recently launched a flood-control project in the area, including a new pump station and a facility to treat stormwater.

Rising sea levels are not at the top of the priority list, Rodriguez acknowledges. “I’m focusing on quick wins and delivering projects,” he says.

At the moment, cleaning up the waterway is considered a key first step in any revitalization plan. A $342 million cleanup plan was approved in 2014, 13 years after the Lower Duwamish was identified as a Superfund site by the EPA. The plan, which is expected to take 20 years, will clean 90 percent of the contaminants from the water, officials say.

For many businesses and residents along the river, rising sea levels remain an abstract concept, compared with the pollution, economic, and environmental issues facing the area, says Stephen Reilly, associate director of ECOSS, a Seattle-based urban environment nonprofit organization. His group has worked with several businesses to raise materials off ground levels and prepare for flooding conditions, but, Reilly says, “most folks are not doing much yet.” Despite the dire forecast, it is hard to devote resources to a long-range problem, he says. “A lot of neighborhoods and businesses don’t have a lot of money to deal with resiliency issues.”

But he sees changes happening. Reilly focused on the section of the ULI study that calls for land along the river to be repurposed for public space and flood control. Fishing is already growing more popular, he says. “Those types of [recreation] spaces will be needed,” Reilly says. “That has a community benefit in addition to flood management.”

For Farrazaino, the rising sea levels are a very real issue. His firm, Equinox Development, is located near the river, about seven feet (2 m) above the mean high-tide line, putting the office on the front line of flooding issues. The ULI discussions about climate change and high tides were encouraging, he says: “I was happy that people were having the conversation.”

But he notes that a large gap still exists between talk and action. “I don’t think we’re at a point when the general population pays attention,” Farrazaino says. “It’s not on the level to make the front pages.” But he believes that now is the time to act on major infrastructure projects. “The long-term issues with sea-level rising need to be dealt with before it’s too late,” he says.

Copies of the ULI Advisory Services panel report on Seattle, Washington, June 21–26, 2015, may be downloaded at uli.org/programs/advisory.

Kevin Brass writes regularly about property and development for the New York Times and the Financial Times.