How can existing buildings be retrofitted to withstand increasing climate risks? It is no secret that most buildings in use today are not prepared to handle stronger storms, higher sea levels, and longer wildfire seasons. In the United States alone, nearly 15 million propertiesface substantial flood risk, and roughly $1.3 trillion of property valuelies in areas at high risk of wildfire.

With two-thirds of 2040’s global building stock already built, these structures must be addressed, according to the ULI Urban Resilience program’s new report Resilient Retrofits: Climate Upgrades for Existing Buildings. Upgrading existing buildings also ensures that the carbon emitted to build the structures does not go to waste and new carbon is not emitted to replace them unnecessarily; upgrades can also add features enabling energy efficiency and use of renewable power, boosting energy resilience during disasters while contributing to net zero goals.

Because Black, indigenous, people of color (BIPOC), and low-income communities are often most exposed to climate hazards, resilient retrofits can also open the door to significant gains in racial and economic justice as a co-benefit for social equity. (See 10 Principles for Embedding Racial Equity in Development for more.)

What design, policy, and funding strategies can support this transformation?

Design

Many strategies for retrofitting buildings apply across multiple hazards and often can support the transition to net zero carbon.

However, some strategies do conflict: for example, adding spray foam insulation to keep buildings comfortable during heatwaves will spike a building’s embodied carbon. How can designers prioritize risk-reduction techniques while ensuring that solutions create co-benefits across resilience and sustainability?

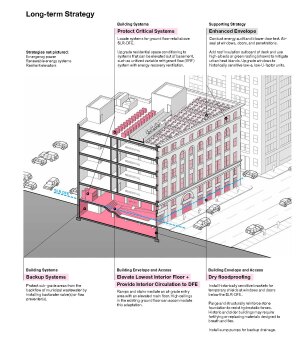

The answer lies in assessing all potential risks at the outset of a project and developing a comprehensive retrofit plan within a larger capital improvement strategy. This method avoids a piecemeal, scattershot approach that will be less cost-effective and may leave opportunities on the table. Planning upfront also allows designers and owners to map out retrofit steps in phases according to available funding or, as risk levels intensify, spread out the burden of implementation over time.

“We’re thinking about renovation of developments holistically, not piece by piece,” says Joy Sinderbrand, vice president of recovery and resilience at the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). “NYCHA has enough lessons learned to say, ‘We’re doing top-to-bottom renovation; what can be incorporated?’ It’s not just repair or bringing up to code, but mitigating risk and placemaking to improve the lives of residents.”

For example, mitigation of severe flood risk can begin with sealing gaps or cracks in foundations and elevating on raised shelves materials stored in lower floors. It can then progress to relocation of mechanical equipment to upper floors (or the addition of flood barriers around them in earthquake-prone areas, where they should remain on lower floors) and finally installation of flood vents or flood barriers against windows and doors.

To increase resilience to flood and high winds at its 701 Brickell property in Miami, owner Nuveen Real Estate has invested in custom flood barriers, elevated transformers within basement electrical rooms, replaced the building’s original generator, caulked windows, replaced sealant on building facades and balconies, and repaired and strengthened facade panels. (Daniel Christensen, CC 3.0)

Evaluating carbon emissions during design can create additional co-benefits. For example, replacing older furnaces burning fossil fuels with rooftop electric heat pumps can save energy and reduce flood risk. In wildfire-prone regions, when a roof with a noncombustible material like metal or concrete tile is replaced, low-carbon options can be specified to reduce embodied emissions. The choice of natural materials for insulation, such as sheep’s wool or straw bale, can even sequester carbon while adding fire resistance.

Policy

New policies are boosting the business case for resilient retrofits. At the global and national levels, for example, binding adoption of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) recommendations is increasing, and the newly proposed U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission rule on climate disclosure will push real estate companies to report how they are managing physical and transition risks to assets and portfolios. Accordingly, resilient retrofits will have to become mainstream, and quickly, or companies will face compliance risks.

It is difficult to design comprehensive retrofit policies that cover the complexity and diversity of a city’s building types, ages, climate risks, and cultural contexts. For example, historic preservation and zoning rules can prevent changes to building facades, such as use of high-performance windows or fire-resistant cladding, or the exceedance of lot lines to add thicker exterior-wall insulation or shading devices.

New local land use and buildings policies can help reduce obstacles by increasing flexibility. For example, New York City recently passed a zoning amendment that relaxes rules on height limits, required elevations of ground floors, and placement of mechanical equipment, while also allowing incremental retrofit options.

Similarly, to target retrofit solutions for the city’s specific building types, Boston has created design guidelines for retrofitting typical building designs—a valuable resource for smaller property owners who may lack access to data and technical expertise. To encourage adoption, the city also has a zoning overlay district that requires certain projects to undergo a resilience review but allows owners to exclude access or mechanical features from calculations of required floor area and open space, for instance, to reduce regulatory burdens on design.

Finance

Resilient retrofits can create a strong business case, built on enhancing asset value; attracting climate-conscious investors, buyers, and tenants; reducing insurance costs; and more. Resilient buildings can adapt to future market conditions, whether environmental or socioeconomic, and are better prepared to deliver returns to all stakeholders despite accelerating climate risks.

However, the funding or financing of resilience upgrades is an obstacle for many property owners. Larger or institutional real estate owners and investors can afford to integrate retrofits into their capital expense budgets, but many smaller owners, as well as communities that face historical and current disinvestment, lack the access to capital to do so.

Although investments in climate adaptation have historically made up a small percentage of climate-related finance, new tools are appearing to provide financing and reduce the burden of upfront investment. For example, Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) financing, which provides upfront capital at long-term, low-interest terms, is increasingly being used for resilience strategies and can be paired with energy efficiency projects to increase returns. Green banks and green bonds are also starting to direct funding to address physical risk, as are green mortgages provided by major lenders like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Grants at the federal, state, and local levels can also help property owners manage costs, whether through Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) programs like the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program and Community Development Block Grants, or through local grants such as those for flood retrofits in North Carolina, hurricane retrofits in Florida, and seismic retrofits in California.

As capital markets, investors, and insurers continue to grapple with the impacts of physical risk on markets, assets, and balance sheets, the availability of capital for resilient retrofits is likely to increase. (See the ULI-Heitman series on climate risk and real estate investment for more.)

Conclusion

As climate risks intensify, resilient buildings will need to become the norm. Fortunately, design, policy, and financing techniques are beginning to come into alignment in support of this new direction. The sooner owners, designers, policymakers, and finance professionals deepen this collaboration and act to safeguard occupants and enhance value, the greater the opportunity.

Learn more: read the full Resilient Retrofits report on Knowledge Finder and register for the Resilient Retrofits webinar, set for May 13.