For decades, highways nationwide were built to connect roads and cities but often came with the added consequence of cutting off those who were already disenfranchised. The federal government and cities across the United States are now making strides to reconnect those communities and right the wrongs of the past.

Many of the infrastructure decisions that are being made today will affect us for decades to come, according to Paul Angelone, senior director of the ULI Curtis Infrastructure Initiative.

“These decisions—how we develop our built environment, whether it’s in the urban core, whether it’s in a suburban environment or in a rural environment—have an impact on our health, have an impact on our wealth, have an impact on our economic being,” says Christopher Coes, assistant secretary for transportation policy at the U.S. Department of Transportation. “That’s why reconnecting communities is so important because we know for the last 50 to 60 years, the way we’ve invested transportation dollars, the way we’ve aligned transportation dollars with land use, in many cases, was sometimes not in the benefit of the full community—and sometimes it’s actually been in direct opposition to neighborhoods.”

President Joe Biden has taken note of the inequities of the past and the infrastructure projects that historically exacerbated racial disparities. It is part of the aim of his $1 trillion infrastructure package that also funds a new Reconnecting Communities Pilot grant program that Coes, a former ULI member, describes as “an opportunity for the federal government to address the misalignment or bad decisions or past harms that we might have made.”

The program includes funding for planning and capital construction projects to bring communities back together by removing or retrofitting infrastructure. A number of cities are now building long-term community value with highway removal projects.

A summer movie screening at the Rose Kennedy Greenway in Boston. The Greenway opened 14 years ago and offers free programming and vibrant public art. It is also 100 percent organically maintained and sustainable and has increased connectivity for the city’s communities and contributed to making Boston a healthier city. (Anthony Crisafulli)

Parks to Unite the Masses

In Dallas, Woodall Rodgers Freeway connects Interstate 35 with North Central Expressway and Interstate 45. It has been considered the busiest road in the city. And when it was completed 60 years ago, its construction came at a high price to those who lived in some of the surrounding neighborhoods.

People who resided in the predominantly Black community of Oak Cliff were profoundly segregated and cut off from downtown Dallas, which helped spur inequity and destitution in that neighborhood.

Now, local officials and private partnerships are working to ameliorate the past with projects such as Klyde Warren Park, which was erected over the freeway. The now-decade-old park connects downtown to uptown Dallas and communities beyond.

“It’s really becoming a stitching back together of communities that were divided with this highway system that just blew right through neighborhoods over the past several decades,” says Kit Sawers, president at Klyde Warren Park. The park receives more than a million visitors per year and was the 2014 ULI Urban Open Space Award winner. “It has established really the center of the wheel for the city,” Sawers says, maintaining that its role is “critically important.”

“There’s a hub now. There’s a vibrancy,” he adds. “Things can grow from it, and it has benefited not only those neighborhoods but the rest of the city.”

The $110 million Klyde Warren Park was funded through a public/private partnership and is located across from the Dallas Museum of Art. The park features an outdoor stage with arts performances and offers movie nights, fitness classes, festivals, and concerts, some of which are sponsored by area organizations. The aim is to provide a venue to “showcase different cultures and talents from around the city,” according to Sawers.

An “enhancement” is being built that will include 1.7 acres (0.7 ha) in addition to the current 5.2 acres (2.1 ha) and that will double the size of the children’s play area.

The park has also had a positive impact on the local real estate market. Over the past decade, the value of the surrounding real estate has increased by $4.1 billion, generating about $525 million in tax revenue. That money will now benefit the city as well as the local school district, roads, and other parks. “It’s truly been the gift that keeps on giving,” Sawers says.

People from around the United States are now viewing the park as a model for similar projects that are in the works in their cities. They are learning from both the successes and mistakes associated with Klyde Warren and its impact on the city. Sawers warns that the programming staff and the budgets for programming should not be underestimated.

Another project, the Southern Gateway Park, also is in the works in Dallas. Its first phase has a planned opening in early 2024 and will ensure that the Oak Cliff neighborhood will no longer be disconnected from the city.

Eric Johnson, the mayor of Dallas, insists that the Southern Gateway Park will be “a game-changinginvestment.”

“Parks can be a catalyst for change that can strengthen our neighborhoods and provide greater opportunities for our residents,” he says. “And it’s my view that parks and trails should be considered critical infrastructure for our city.”

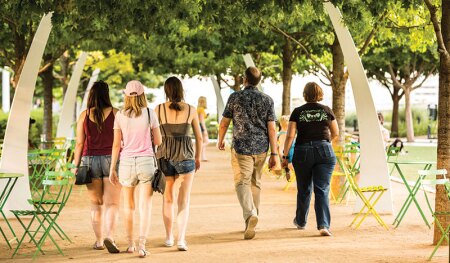

People walking in Klyde Warren Park. The now- decade-old park was erected over a freeway and connects downtown to uptown Dallas and communities beyond. Located across from the Dallas Museum of Art, it features an outdoor stage. The park receives more than a million visitors a year and was the 2014 ULI Urban Open Space Award winner. (Courtesy of Klyde Warren Park)

Austin Weighs Impact on the Community

Across the state in Austin, plans are underway to improve Interstate 35, which divides east Austin and downtown Austin. The I-35 Capital Express Central Project will entail lowering the road and removing the current decks located there. Having cap and stitch in the project, which would be built by local government, is what makes it vitally important.

(Caps consist of decks that are built over freeways that have been lowered or rebuilt underground. Stitches involve widening bridges over parts of a freeway that have been lowered and can feature designs that include bike lanes, wider sidewalks, and space for parks.)

“By introducing pedestrian-accessible and community activated spaces across what was the highway barrier, we have the opportunity to reconnect downtown and east Austin,” says Paulette Gibbins, executive director of ULI Austin.

The new project has major real estate implications—many of them positive—but it could also negatively affect some residents, since lowering I-35 and activating cap and stitches could raise the value ofnearby land.

“Increased land value increases property taxes and may cause many current east Austin residents to move,” Gibbins says. “With no income tax in Texas, our property tax is very high and can be a cause for displacement either through inability to pay property tax or raised rents due to raised property taxes.”

Gibbins adds that rents may also increase as gentrification takes place since the property will be more valuable. Displacement may occur if landlords decide to cash in their property as well, she says.

Reimagining the I-35 corridor. In Austin, the I-35 Capital Express Central Project will include lowering the road and removing the current decks located there. A grassroots campaign, Reconnect Austin, a 2018 ULI Austin Impact Award Next Big Idea winner, aims to establish I-35 as public space. (Reconnect Austin)

“Taxing and government entities need to consider options to limit this displacement by freezing property tax assessments or implementing property tax forgiveness programs within the area affected by this project if showing that affordable housing is being achieved,” Gibbins says. “Since most of our property tax bill is not from the city, it will take all the taxing entities to work together to realize relief for current residents. The best outcome for communities of color can only be realized if steps are taken to mitigate displacement resulting from this project.”

Linda Guerrero, who co-chairs the I-35 Coalition and is running for Austin City Council, says that a steering committee should be established to best support the local communities and calls it a“key step.”

“The establishment of a steering committee will provide the I-35 Coalition group a core base of leadership to coordinate and plan regular meetings, and strategize how to move the work forward during the duration of the process,” Guerrero says. “The steering committee will be able to publicly represent the goals of the I-35 Coalition. They will work collaboratively with the [city of Austin] and [Texas Department of Transportation] to advocate for their shared community values to ensure a better future for I-35 going forward.”

A grass-roots campaign, Reconnect Austin, a 2018 ULI Austin Impact Award Next Big Idea winner, aims to establish I-35 as public space. The goal is for it to serve as a boulevard that reconnects neighborhoods while also providing land for new businesses and possibly affordable housing projects.

Boston and the Rose Kennedy Greenway

Across the country, Boston’s Central Artery/Tunnel Project, also known as the Big Dig, redirected the Central Artery of I-93 into a tunnel system underground. This allowed for a public park to be built in its place.

“The Central Artery that predated the Greenway was built in part by destroying neighborhoods, especially homes,” Cook says. “Its elevated highway separated Boston from its waterfront and people from each other. The Rose Kennedy Greenway now brings those same neighborhoods and their people together.”

The Rose Kennedy Greenway in Boston opened 14 years ago. Similar to Klyde Warren Park, the Greenway offers free programming as well as “vibrant public art that promotes equity and inclusion by welcoming and supporting Boston’s diverse neighborhoods,” according to Chris Cook, executive director of the Rose Kennedy Greenway.

The Greenway is 100 percent organically maintained and sustainable and has increased connectivity for the city’s communities and contributed to making Boston a cleaner, healthier city, according to Cook.

“Combined with the cleanup of Boston Harbor, this project has unlocked tremendous economic value and opportunity for downtown Boston and beyond,” Cook says. “The physical connection of the park and quality of the design are incredibly inspiring. However, what really connects people is the inclusive and engaging programming and public art of the space. Parks are for people.”

A rendering of the streetscape in the Rondo community project, now in the predevelopment phase. A feasibility study says the land bridge could allow for 13 acres (5.2 ha) of public space, which could accommodate 576 new housing units and 108,000 square feet (10,000 sq m) of retail space and also generate $4.2 million in annual revenue for the city. (HGA)

Reconnects a Community of Color in the Twin Cities

During the 1950s, Interstate 94 bore through a St. Paul neighborhood and displaced 700 homes and 300 businesses, according to the nonprofit Reconnect Rondo. It devastated the once-vibrant community where it is estimated that at least half of St. Paul’s Black residents once reportedly lived.

Reconnect Rondo’s goal is for the land bridge to cap I-94 and connect St. Paul’s African American community of Rondo, according to Keith Baker, executive director of the Minneapolis-based organization. A recent ULI study found that erecting a land bridge in Rondo would definitely be advantageous to the local Black community.

“Through it all, stakeholders agreed that the Rondo Community Land Bridge is a worthy investment not only to realize a physical connection that would enhance livability, but also to provide an opportunity for long-overdue social justice for a neighborhood,” the 2018 study states. The idea of a land bridge dates back to 2009 and the nonprofit organization has secured $6.2 million for predevelopment from the Minnesota Legislature.

“There was a transit project—the Central Light Rail Corridor project—that was going to be going through from Minneapolis to St. Paul along University Avenue,” Baker explains. “University Avenue cuts through the northern portion of the Rondo community, but there were no stops planned in the community of Rondo. Naturally, the community was upset by that.”

Community meetings were held and, as a result, residents let it be known to the Federal Highway Administration that something needed to be done to remedy the issue. This funding includes consideration for a land bridge that could allow for 13 acres (5.2 ha) of public space, according to a recent feasibility study, which also indicates that they could have around 576 new housing units and 108,000 square feet (10,000 sq m) of retail space and also generate $4.2 million in annual revenue for the city, according to Baker. The project is projected to yield 1,800 new jobs and provide space for a business incubator.

“If you can imagine, there were 300 businesses taken in Rondo,” Baker says. “We envision 300 businesses replaced.” Reconnect Rondo is now focused on the idea of creating an “African American cultural enterprise district” that was first imagined in 2015 by the Rondo Roundtable initiative and what was once Rondo prior to the freeway destruction.

The project is in the predevelopment phase. The goal is to honor the area’s historical culture and simultaneously celebrate the city’s current diversity “while setting conditions for the future,” according to Baker. Such projects nationwide are key to President Biden’s plan, according to Coes.

“We’re trying to leverage every dollar and cent of the bipartisan infrastructure law to reinvest in disadvantaged communities, particularly those that have been harmed by infrastructure investments or bad planning,” Coes says. “We really recognize that we need a public/private/people partnership to do that. ULI definitely stands as one of those organizations that can help facilitate that at the local level.”

The idea of using such projects to bring neighborhoods together is not solely an American phenomenon. For instance, in Antwerp, Belgium, there is a Ringland Project that would consist of a huge project to cap the ring in some areas. It is being led by the local community “in a new and exciting way,” according to Angelone. The ULI Infrastructure and Transit-Oriented Development Product Council researched the project. And South Korea’s Cheonggye Freeway stands as yet another example of an urban highway that was turned back into a stream to provide public green space in the middle of downtown Seoul.

As federal dollars are spent to remove highways and create more equitable communities, “ULI members need to be engaged in the process so we can create these better spaces,” says Angelone.

KAREN JORDAN is a freelance journalist based in Los Angeles.