Though the sustainability movement has been putting more focus on human health recently, it is less of a trend than a returning to its roots. William Penn’s "" plan of 1683 paved the way for Philadelphia to be the first American city to provide free hospital care at the heart of the city. The history of public health reaches back to America’s beginnings: the country’s first hospital was cofounded in Philadelphia by Benjamin Franklin in 1751. Philadelphia was also home to the country’s first medical school, children’s hospital, cancer hospital, nursing school, and dental school.

In 2012, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHoP), a private institution, partnered with the city to serve residents in South Philadelphia, an area beyond the historic Center City located between the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers and bisected by the central arterial, Broad Street. The site is located between Morris Street and Castle Avenue with frontage on Broad.

Philadelphia-based VSBA Architects, together with its clients, led the programming and design for the South Philadelphia Community Health and Literacy Center. Its program includes a Department of Public Health community health center, a CHoP pediatric primary care clinic, a branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia, and a community park and recreation center operated by Philadelphia Parks and Recreation.

This public/private effort is unprecedented in the variety of services located on a single site, in the speed of gaining public approvals, and in the financial mechanisms supporting the development. “Spurred by strong planning and design momentum, enhancing programmatic outcomes for city services is central to our investment decisions,” says Mike DiBerardinis, managing director of the City of Philadelphia.

The 93,000-square-foot (8,600 sq m), three-story structure embodies ULI’s Ten Principles for Building Healthy Places. Beyond efficiency gains and environmental sustainability, it demonstrates how the whole can far exceed the sum of its parts. The building, which is targeting a Silver rating under the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program, fully embraces the ten principles:1. Put people first.The center adopts the “complete streets” principle of ensuring access for pedestrians, drivers, cyclists, and users of public transit. Multimodal transportation prioritizes people over cars with the intent of reducing fatal crashes and injuries. A resident-focused planning process involves community engagement and multiple surveys to address resident aspirations and concerns. The facility’s public areas are filled with natural light, and corridors in the clinics are punctuated with end windows that provide light and views to the outside. Access to views of the natural environment has been shown to reduce pain for patients and speed recovery.2. Recognize the economic value.Adjacent to a transit stop and two intersecting bus routes, the center has a high level of connectivity while creating a friendly presence on the street, attracting foot traffic. At the back of this active hub, a newly contoured park increases the potential for higher property values in a transitional neighborhood.3. Empower champions for health.With the support of Philadelphia’s mayor and CHoP’s chief executive officer, the empowered team leaders engaged in a collaborative process that included monthly steering committee meetings. These champions put in motion the cooperation needed among the hospital, the federal government, and myriad city departments, including Parks and Recreation, Public Health, the Free Library, Public Property, Law, Finance, and Innovation and Technology.4. Energize shared spaces.From the large entry plaza to the active playground, the building has been carefully massed and detailed to respect its neighbors and welcome visitors. Limited parking, located between the library and recreation center, is screened from view. On the ground floor, library meeting rooms are open for use by the community and all building occupants. The park and sidewalk, places for greater social interaction, will be planted with more than 30 trees. Trees not only provide summer shade, but also have been linked with .5. Make healthy choices easy.The walkable neighborhood, availability of transit, and safer bike lane design make active transportation the natural choice. Public art is another tenet of active design, and the relocated sculpture on Broad Street enlivens this emerging healthy commercial corridor. The proximity of the park and recreation facility allows more doctors on site to prescribe the Nature Rx program, which calls for pre-diabetic patients to exercise rather than take medication to address obesity, high blood pressure, chronic stress, and a poor attention span.

6. Ensure equitable access.Not only do facilities qualify as fully accessible under Americans with Disabilities Act guidelines, but also the plaza design anticipates future installation of an elevator providing people with disabilities a connection to the subway. The creation of a shared entrance is intentional, supporting health equity among the clinics and patients with different types of health coverage. Green materials are another equalizer: the entire building uses paints and primers with low or no volatile organic compound (VOC) content, as well as formaldehyde-free materials, in order to enhance indoor air quality and reduce health conditions triggered by the environment, such as asthma.7. Mix it up.Providing access to a multifaceted mixed-use building, the entry plaza has been designed to accommodate the many people who wait outside for walk-in hours at the health clinic. The shared public foyer further encourages chance encounters among multigenerational visitors. The scale and materials of the building change on the side facing the residential neighborhood, and a metal picket fence along the basketball courts provides a more inviting park enclosure than the traditional chain-link fence.8. Embrace unique character.Broad Street’s importance is reflected in the civic scale of the curtain-wall facade, and brick facades respect the character of the flanking streets of rowhouses. The parking lot entrance and exit are located near Broad Street to minimize neighborhood congestion and noise. A rain garden inside the park supports citywide green strategies to manage stormwater. Reflecting each facility’s separate personality, emphasis on lighting and color coding enhances wayfinding and adds visual vibrancy to the interior corridors, walls, and floors.9. Promote access to healthy food.While the absence of traditional vending machines offering sugary drinks both promotes good health and saves energy, street carts at the entrance plaza offering fresh fruit and water fountains in the interior public area are readily available. An amenity for nursing mothers are the separate lactation rooms for staff and patients; research demonstrates that breast milk helps compared with formula.10. Make it active.Active indoor and outdoor spaces—from a colorful play area in the park to large glazed windows among cast-stone piers conveying activity within—are central to the design. In the atrium, a prominent staircase is placed close to the entrance, encouraging use of the stairs and leaving the elevator for those with acute needs.

Beyond these principles, colocational synergies are emerging even as the building nears completion, scheduled for this spring.

A neighbor is formalizing a pre-kindergarten book exchange benefiting the entire community. Also, the Penn Center for Public Health Initiatives recently formed a partnership with the library to incorporate evidenced-based health programming, enhancing linkages to social services, food, nutrition, and culinary literacy. This branch library, with user-friendly furnishings and a flexible floor plan, will be the first implementation of the Building Inspiration: 21st Century Libraries Initiative in the Free Library’s master plan.

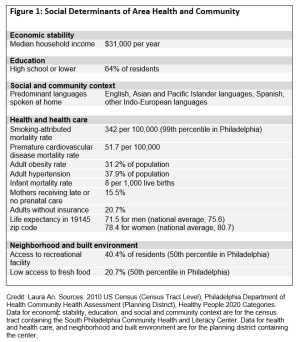

Social determinants of health (see figure 1 below), inextricably linked to land use and the built environment, is a concept championed by the and leading health organizations. Though Philadelphia is the nation’s fifth-most-populous city and is known for its major health care institutions, its residents rank below average in some key health indicators, such as infant mortality rate, premature cardiovascular mortality, adult hypertension, and prevalence of adult diabetes.

“Urban centers often have high rates of poverty and also the greatest health challenges, illustrating the social determinants concept,” says Donald Schwarz, director at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and former deputy mayor of Philadelphia. “But Philadelphia has been working hard to improve the health of all its residents, with the idea that better health gives people a greater opportunity to rise from poverty.”

Siobhan Reardon, president and director of the Free Library of Philadelphia, concurs. “We are excited about the potential to serve our customers better in a building that has 21st-century design thinking, programming, and a new community health initiative that will engage all our collaborators,” she says.

The project budget of $42.7 million for the facility is broken down as follows:

- City of Philadelphia—$2.2 million,

- CHoP financing/sponsor equity—$32.5 million; and

- New Market Tax Credits equity funds—$8.0 million.

The legal transactions involved in bringing the project to fruition were complex, including a ground lease, a prime lease, and an operating agreement facilitated by the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC). PIDC also structured a large allocation of the New Market Tax Credits with JP Morgan Chase, Commonwealth Cornerstone Group, and City First Bank.

The new project reduces future city maintenance needed for the current buildings’ aging infrastructure. The city’s contribution was the 1.6-acre (0.6 ha) prime development site and $2.2 million in tenant fit-out for the recreation, library, and health facilities. Building on its large portfolio, CHoP has ample experience in institutional construction and tax credit financial structures.

“The CHOP’s mission is aligned with the city’s for serving this neighborhood, and through this synergy we are able to innovate and push through systemic constraints, creating a new colocation paradigm with enhanced outcomes,” says Doug Carney, CHoP senior vice president for facilities and real estate. “During construction, our team had also hired local residents to lead neighborhood cleanup to instill a strong pride of place.”

In addition to attracting capital investment, such as the New Market Tax Credits, the center has retained 138 positions from the old recreation center and library, so no jobs were lost, and created 234 construction jobs and 12 permanent jobs. After construction, the community impact will include improved services to 35,000 library users each year, an increase of 50 percent in the number of patients for both city and CHOP clinics at the site, and use of the recreation center by 4,000 people each week.

Unlocking the full health potential in place making has been demonstrated in recent development projects such as Mariposa, a 15-acre transit-oriented development near downtown Denver, and Paseo Verde, a mixed-use development in North Philadelphia.

The center stands on the shoulders of these precedents and adds an integrated programming dimension to be sustained through an ongoing steering committee led by the clinics, library, and recreation center. The success of this colocation will be further measured by programs and revenue streams yet to be conceived. In the future, new wealth in neighborhoods will move far beyond property values and increased services toward metrics measuring health, well-being, and social cohesion.

Joyce Lee is president of IndigoJLD, providing green health, design, and planning services on leading-edge projects. She is a fellow of the American Institute of Architects, a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) fellow, and has been a fellow at the National Leadership Academy for Public Health.