Given the economic and environmental benefits of energy efficiency renovations, two questions arise: why are they not happening faster, and does the government have a role to play?

A library in Frankfurt, Germany, hires an energy management company that replaces the lighting, changes the cooling system, and modifies the heating and power supply. The total cost is €600,000 ($949,000). These energy-saving measures result in a one-third reduction in the building’s energy consumption and save the library €120,000 ($190,000) per year. This annual savings allows the library to repay the energy management company that financed and implemented the renovation out of its savings over the next ten years. Ditmar Hinsberger, the library building manager, is able to do this renovation without investing any capital. In addition to obtaining improved space, part of the €600,000 pays for much-needed furniture and equipment for the library. Ditmar also points out that the renovation reduces the library’s energy use by 1 million kilowatt-hours per year.

Thousands of examples exist of equally successful renovations of hospitals, schools, and other public buildings. Replacing an old furnace and boiler in an existing office building can cost $250,000 and result in an annual savings of $100,000 to $200,000, meaning less than a three-year payback. Companies with strong balance sheets like Johnson Controls, Siemens, and Honeywell are willing to secure the capital for the renovation and guarantee the energy savings, virtually eliminating the owner’s risk.

The benefits of energy conservation, using existing technology, is strongly supported in McKinsey and Company’s landmark December 2007 study “Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions: How Much and at What Cost,” which highlights the savings from improving energy efficiency in buildings and appliances as the option that costs the least and is most economically viable.

Given the economic and environmental benefits of energy efficiency renovations, one might ask two questions:

- Why are they not happening faster? For example, in Germany, which leads the world in this arena, only 7 percent of the public buildings (and far fewer privately owned properties) have undergone energy efficiency renovations.

- Does the government have a role to play? Of five key government programs and policies being implemented in Europe, which would make sense in the United States and elsewhere, and which ones would not?

Barriers to Retrofitting

The rule of thumb in renovating buildings is that it is relatively easy and cost-effective to reduce energy consumption by 30 percent in most older commercial buildings. In fact, energy management companies will often guarantee specific savings like 28 or 32 percent as part of a performance management contract, and pay the difference if that amount of savings is not achieved. These energy services companies also will secure funding for the upfront costs and accept repayment exclusively from all or a portion of the money saved through lower energy bills. At first blush, this concept sounds almost too good to be true. What’s the catch?

Time and hassle. For an energy management contract to work, the building owner and the energy management company need to establish a baseline. How much energy and electricity is the building currently using? This energy audit creates considerable disruption for tenants. In addition, there are significant contractual complexities such as distinguishing between those future savings that are due to greater efficiency, those that occur because a tenant moves out, and those due to unusual weather. A number of building managers say it is hard to convince the owner of the building to purchase an efficient-building energy package because of its complexity.

Control. If the energy management company is going to guarantee the savings, it needs to have some control to ensure that the equipment in the building is well maintained and operating in the most efficient way. Several property managers in Europe say significant savings could be achieved by effective maintenance regimes, including simple procedures like making sure all filters are kept clean. Energy management companies also are concerned about tenant behavior. To achieve significant energy savings, tenants need to cooperate by turning off lights and keeping the temperature in their space at a reasonable level. Technology and controls only get you so far.

Conflicting incentives between landlords and tenants. Over the years, leases in most commercial buildings have shifted the payment of operating expenses from the landlord to the tenant. In some cases, this shift is achieved through submetering, in which the tenant pays directly for the actual use, such as electricity bills. In other cases, using triple-net leases, all the building’s operating expenses are paid by the landlord and then passed through and reimbursed by the tenant. Even in leases where the landlord pays the base operating expenses, there is usually a provision in the lease that states that increases or decreases in operating expenses after the first year are passed through to the tenant. Thus, there is a misalignment of incentives, with the landlord responsible for the capital costs for making the building more energy efficient, but the tenants benefiting from the savings. Martin Melaver, CEO of Georgia-based Melaver Inc., indicates this is also the key issue behind the slow adoption rate for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design for Existing Buildings (LEED-EB) standards for multitenant buildings.

In a building with a single tenant on a long-term lease, this misalignment can be rectified by either having the tenant pay for the renovation, or by having the tenant agree to pay some or all of the savings in additional rent. For this reason, most of the energy efficiency renovations have been to single-tenant, owner-occupied, or public buildings. In a multitenant building, it would be very time-consuming for the owner to go to each of the tenants and negotiate a lease amendment that enables the landlord to be reimbursed in some way if the building consumes less energy. It would also be hard to explain this surcharge to a potential new tenant.

The profits are small. With utility costs in U.S. office buildings averaging about $2.50 per square foot ($26.90 per sq m), a 20 percent reduction in energy use yields savings of 50 cents per foot ($5.40 per sq m), notes David Pogue, national director of sustainability for CB Richard Ellis. Even if the owner could keep 100 percent of those savings and even if it only cost $3 per square foot ($32 per sq m) in renovation costs to achieve those savings, the building owner would only receive an extra $50,000 in income in a 100,000-square-foot (9,300-sq-m) building. Contrast that $50,000 with the extra revenue and profit that the landlord could achieve if he or she spent this same amount fitting out and leasing 10,000 square feet (930 sq m) of office space. The new office lease might result in five times as much income flowing to the bottom line.

Government Involvement: Lessons from Europe

Although cities like New York City and San Francisco have created incentives to get developers to build energy-efficient buildings, European governments, especially in Germany and the U.K., have been far more aggressive. If the U.S. government and other European countries want to take a more active role, they might want to emulate three of these programs that relate to standardized reporting, banning certain products, and providing low-cost financing. On the other hand, some of the programs in Europe, such as creating zero-energy buildings and establishing rigid requirements, probably should be avoided.

Standardized reporting. A simple and effective role for government is to raise awareness through standardized reporting. According to the Carbon Disclosure Project, a U.K.-based organization that works with shareholders and corporations to disclose the greenhouse gas emissions of major corporations, fewer than half the companies in the S&P 500 provide a detailed public accounting of their emissions. In the U.K. starting this past April, all companies that used over 6,000 megawatt-hours of half-hourly metered electricity in 2008 must report annually on their electricity use. They are even required to submit a “footprint report” online. Simply getting this information into the public arena may spur significant activity. It helps the industry to overcome one of the barriers to retrofitting—the time and hassle of developing a baseline. It also creates an incentive for tenants to work with the landlord to reduce energy use.

In the Czech Republic, the law requiring mandatory energy audits by large users has been effective. According to the Joint Research Center, which provides scientific advice and technical know-how to the European Commission, “the introduction and enforcement of obligatory audits have had an important role in making the Czech ESCO [energy service company] market one of the European frontrunners.”

Another benefit of requiring standardized reporting is that it creates competitive and public relation pressures.

If the United States follows the U.K. and Czech model and requires large organizations to report their energy consumption, it will provide an incentive for large tenants to rent space in more energy-efficient buildings.

A related approach that uses reporting and benchmarking to spur conservation is spelled out in New York City’s PlaNYC. “By 2030, we project that 85 percent of our energy usage will come from buildings that already exist today; as a result, we cannot simply rely on new buildings to be more efficient,” the program’s 2009 progress report states. To ensure that existing buildings become more efficient over time as part of PlaNYC, Mayor Michael Bloomberg wants buildings in New York City with over 50,000 square feet (4,600 sq m) of space to benchmark their energy consumption annually. For its 4,000 government buildings, New York City will deploy TRIRIGA software to monitor and help reduce energy use and greenhouse gas emissions.

Banning products. Another European strategy other countries might emulate that leads to greater energy efficiency in buildings is to simply ban some of the most wasteful products. For example, incandescent lighting is inefficient, using about ten times as much electricity as fluorescent and light-emitting diode (LED) lighting. In Germany and Australia, sale of incandescent bulbs is being phased out, starting with 100-watt bulbs, then working down to 75-watt bulbs, 50-watt bulbs, etc. Incandescent bulbs have to be replaced more often and are more expensive when the cost of electricity is factored in. Nevertheless, consumers continue to buy them because the initial cost is lower. From a societal standpoint, however, other factors like the need to build more power plants and the desire to meet its obligations under the Kyoto Protocol made lightbulbs an easy target for the German government, especially because a good alternative exists. In the United States, chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were banned in 1974. It merits consideration whether phasing out and then banning incandescent bulbs would be a good idea, and whether it would spur even greater efforts to improve LED lighting and other potentially more efficient products.

Providing access to low-cost financing. In Germany, to spur energy retrofits, the government provides low-cost financing through Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW), a government-owned development bank. KfW does not make direct loans to building owners, but instead lends to German banks, which in turn make loans to households and businesses that want to invest in making their buildings more energy efficient. Because it has the guarantee of the German government, when KfW goes to the capital markets, it can obtain all the low-cost capital it needs for lending to commercial banks, says Sebastian Conrad, a loan officer at KfW. Customers can borrow money for energy retrofits at rates currently ranging from 2.5 to 6.5 percent.

To qualify for this kind of loan, the investment must meet certain criteria, including that it reduce energy consumption by at least 20 percent. A side benefit of having the government involved is that it has trained the banks to do this kind of lending—a complicated process because securing collateral for these loans is difficult. But the track record has been so good that in Germany ample money is available for most projects, either through KfW or directly from the banks.

An interesting precedent for this kind of financing exists in the United States, points out Peter Stein, a general partner at the Lyme Timber Company in Hanover, New Hampshire: the Clean Water State Revolving Fund, a self-perpetuating loan-assistance authority for water quality improvements. Like KfW, this fund provides low-cost loans to states, which in turn lend it to cities and towns, farmers, homeowners, nonprofit organizations, and small businesses. Since 1988, the fund has provided $65 billion in financing for 20,711 water quality projects. The combination of state matching funds, interest earnings, and the revolving nature of the fund means that to date for every $1 of federal money, the fund has financed $2.31 of clean water projects.

Approaches to Avoid

These first three approaches merit careful consideration by the U.S. government, state governments, and other countries, and perhaps adoption with some modifications. However, other regulatory approaches used by European governments provide lessons in what U.S. regulators might want to avoid.

Setting unrealistic targets. When the European Parliament decreed that by 2019 all new structures built must be zero-energy buildings, one might have concluded that the Europeans had discovered a new technology that enabled them to meet this impressive standard. It turned out not to be the case. While it is possible using current technology to create a building with photovoltaic cells, on-site windmills, and superinsulation so that it uses zero off-site energy, doing so would be possible only in a limited number of locations—and in most cases, it would be cost-prohibitive. “It is a very long way from the few dozen zero-energy buildings—which exist under optimal climatic conditions in California, China, the U.K., and Germany—and the mandatory application of a zero-energy standard,” writes Eberhard Rhein, adviser to the European Policy Center in Brussels.

If one really wants to reduce energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, those extra dollars probably could be better used in renovating buildings already in use.

Requiring specific products rather than general outcomes. In the field of energy efficiency for both new and older buildings, it would be better to set performance targets and give developers and owners broad latitude in choosing the best methods and materials to achieve those results. It may lead to better buildings, better results, and more innovation.

The Building Owner’s Perspective

The decisions that individual building owners make will determine the number and scale of energy efficiency retrofits. The government can play an important role in the short term by creating incentives in the form of reporting requirements and access to inexpensive capital. Over the longer term, three other factors will have an even stronger influence on building owners—energy prices, tenant requirements, and climate change.

Energy prices. If energy prices remain relatively high and continue to rise, the economics of energy efficiency retrofits will become increasingly attractive. An eight-year payback can become a four-year payback. High energy prices will also spur innovation. In lighting, for example, new technologies like LED lighting are advancing rapidly. For specific applications like outdoor lighting and exit signs, LED lighting is already the best choice, says David Robinson, vice president of Hines. If LED lighting technology continues to improve, Robinson expects it ultimately to replace fluorescent lighting in offices and greatly reduce energy consumption. Even if the price of fossil fuels does not increase significantly, some kind of carbon tax—such as the one being implemented in the U.K. under the Carbon Reduction Commitment (CRC) Energy Efficiency Scheme cap-and-trade system—may greatly enhance the economic returns from energy efficiency retrofits.

Tenant requirements. If tenants demand greater energy efficiency, building owners will respond. Some of the strongest credit tenants such as the U.S. Government Accountability Office and General Electric will only rent large spaces in buildings that are LEED certified or otherwise shown to be energy efficient. The genius of the U.K. reporting requirement is that it will make all companies more cognizant of the amount of energy they are using and provide additional impetus for them to rent space in energy-efficient buildings.

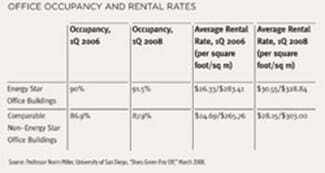

Tenants are already demonstrating a strong preference for such spaces. A study conducted by Norm Miller, director of the Burnham-Moores Center for Real Estate at the University of San Diego, shows that rents and occupancy rates at Energy Star–rated office buildings are consistently higher than those at comparable non–Energy Star buildings (see table, page 64).

One thing that might spur more energy efficiency renovations is if the Building Owners and Managers Association (BOMA) or some similar organization created standards for calculating operating expenses per square foot, tenants insisted on seeing these numbers, and it became a significant factor in the decision about where tenants chose to lease space.

Climate change. If the United States and many other countries sign a treaty and pledge to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions in the next few years, reducing energy use in buildings will be a key part of the strategy.

The Green Lease: A Different Approach

Real estate professionals now talk about “green leases” in which landlord and tenant incentives are better aligned. But this is not easy. One approach might be to create a three-party agreement among the landlord, an energy management company, and the local utility. The energy management company would finance and install a new furnace, for example, and also guarantee a 20 percent savings. The utility company would serve as an intermediary and add a green finance charge to the building utility bill, which would repay the energy management company over a fixed period.

From the owner’s perspective, this arrangement means his building gets a new heating system without any expenditure on his part. From the tenants’ perspective, their utility bill goes down because the energy savings from the new furnace are greater than the new green finance charge. From the energy management company’s perspective, additional, profitable business is obtained. The utility company receives a fee for acting as a financial intermediary and a reduced need to build new power plants. Something like this arrangement with a green finance charge billed by a utility might provide a useful framework.

“There are about 5 million commercial buildings in the United States consisting of 72 billion square feet [6.7 billion sq m] of floor space,” says Ian Campbell, Johnson Controls vice president of global energy and workplace solutions. “Cost-effective retrofit potential remains for over 80 percent of these buildings.” With such a large and attractive market, energy service companies will find a way to spur activity.

To maximize energy savings, landlords and tenants need to work together. The process might begin with a conversation about mutually agreed-upon energy savings goals. This might lead to the installation of controls, gauges, and submeters so that information about electricity and energy use is transparent and easy to understand. It can be a win-win situation in which everyone benefits from the savings in terms of lower costs, greater comfort, and a smaller carbon footprint.