The story of St. Paul, Minnesota’s Rondo neighborhood has echoes in the development of dozens of other American cities.

In this African American neighborhood, residents were segregated from their neighbors by official laws and unofficial discrimination. But the cross-class nature of the community (80 percent of St. Paul’s Black community lived there) ensured that there was a thriving economy that supported businesses and livelihoods despite the larger oppressive context.

From the perspective of white planners and policymakers, however, the area was nonetheless designated a slum. When Interstate 94 was constructed in St. Paul, its path ran through the heart of Rondo.

“Rondo was a growing middle-class community in the ‘50s, before the freeway came,” said Keith Baker, executive director of ReConnect Rondo, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that strives to bring prosperity to the Rondo neighborhood. “You can see a 61 percent population decline took place between 1950 and 1980. We lost 48 percent of homeownership in the area. That’s a pretty devastating gutting of a community.”

This pattern was repeated in many U.S. cities. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 funded the creation of the interstate highway system, and its construction moved the equivalent amount of soil as 116 Panama Canal projects. It also displaced more than 1 million residents, disproportionately affecting African Americans and other marginalized groups.

But at the Urban Land Institute’s Restorative Development: Infrastructure and Land Use Exchange forum in February, Baker and his compatriots at ReConnect Rondo described their plan to address, even undo, some of that traumatic history.

Members can access a recording of the discussion on ULI’s Knowledge Finder.

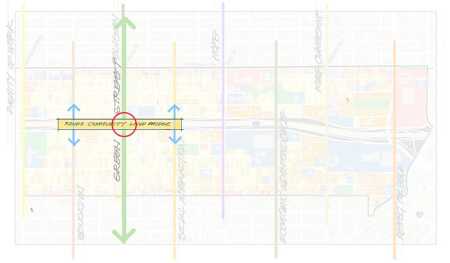

Already years in the making, their proposal would place a cap on a substantial chunk of I-94 and create a new 24-acre (9.7 ha) neighborhood on top of it. The idea is to create park space and other cultural amenities, hundreds of permanently affordable homes, and a local business corridor (200 Black-owned businesses were destroyed by the historic highway project).

At the February meeting, Baker and his colleagues laid out the history of Rondo, their conception of the land bridge across the highway, and how they plan to engage with the community around the massive undertaking.

“I keep thinking about missing teeth . . . we all know what a dental bridge is,” said Joshua McCarty, chief analytics researcher at the consultancy firm Urban3. “That’s a great analogy for what we’re talking about here, restorative development like restorative dentistry. We have parts of our city that are intact [and parts] that are missing.”

The idea is to create a moral and financial case for bridging those missing teeth.

The land bridge project could cost at least $450 million to complete and is still in the planning stages. The state of Minnesota has supplied a starting round of $6.2 million in funding while the local Metropolitan Planning Council offered $150,000 to study community fears about gentrification. Funds from the bipartisan federal infrastructure act are expected to be tapped for the project as are more state dollars.

Those numbers might sound daunting, but Baker ticked off some comparison points: $348 million in state funding for the U.S. Bank Stadium, where the Minnesota Vikings play football, and $550 million for Target Field, where the Minnesota Twins play baseball.

“What we’re requesting here is not new in terms of infrastructure investment into a proposition,” says Baker. “But we are requesting that this kind of investment happen within communities and neighborhoods in a way that is much more effective. We can measure direct benefit from that investment, which I don’t believe that we can do on either of [those other two stadium projects]. It’s not a criticism, but about a shift of a narrative of what we mean by investment in neighborhoods.”

The Reconnect Rondo feasibility study showed the possibility of 576 potential new housing units, 1,800 new jobs, new retail space of 140,000 square feet, $4.2 million more in annual revenue to St. Paul, and a generator of economic growth where there is now a hole in the ground.

“In a lot of neighborhoods, like Rondo, the embers are still very much there,” said McCarty. “If we would give the fire a little oxygen, it would take off.”

The fire in McCarty’s analogy, he noted, was a stand in for “market values and development.” For neighborhood residents distrustful of market rate real estate interests, ReConnect Rondo is also devoting a lot of energy to figuring out how to make sure their project is equitable and inclusive. In previous interviews, leaders of the group have talked about establishing a community land trust to ensure that the homes built on the highway cap could be kept permanently affordable. The city is also exploring inclusionary zoning options, to ensure a degree of affordability even with market rate development.

Reconnect Rondo also wants to institute a “right to return” that would allow those residents who can prove their families were exiled from the original neighborhood the first opportunity to move back. They have also drawn together the “Rondo Roundtable,” an umbrella of African American led nonprofits to advise the project and ensure community buy-in.

“[Some longtime residents confronted with new projects say] ‘we don’t want this development because it’s going to hurt us again,’” says Baker. “We’ll flip the script. The developer is Rondo, is from Rondo…that deflates a lot of the fight. When people are benefiting from this, they’re not going to fight this.”