Following the 2014 completion of the dramatic One57 tower by Extell Development, a raft of new tall and slender buildings is set to change the midtown Manhattan skyline in New York City. Many are above the 984-foot (300 m) measure used by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat to qualify as a supertall building, and most are designed to take advantage of Central Park views.

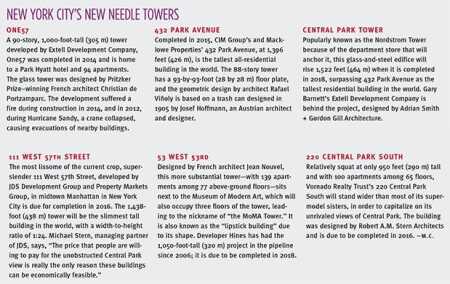

The 1,000-foot-tall (305 m) One57, on West 57th Street, was the first of this new wave and was briefly New York’s tallest residential building, but it has been surpassed by the 1,428-foot-tall (435 m) 432 Park Avenue building. Estimated to be completed by 2018, both will be surpassed by the 1,522-foot (464 m) Nordstrom Tower as well as by the not-quite-as-supertall—but superslim—111 West 57th Street building, which will rise to 1,438 feet (438 m) tall with a tiny floor plate of 60 by 80 feet (18 by 24 m).

Ming Wu, design principal at architect Perkins Eastman, says, “In New York real estate terms, the appearance of needle towers on the skyline is a very recent phenomenon. At present, in Manhattan, there are easily a dozen or so needle towers being planned or under construction—and ranging in height from 900 to 1,500 feet [274 to 457 m], so this phenomenon is significant and will dramatically alter the city’s image. Many will surpass the Empire State Building in height, and will rival the [1,776-foot/541-m] Freedom Tower in prominence.

“Interestingly, as tall as these condominium and mixed-use towers are, they have relatively small residential floor plates, often with a single apartment occupying an entire floor in the upper reaches. Thus, the number of apartments in a ‘needle tower’ is small, generally ranging from approximately 100 to 175, and in some cases fewer than 100 [units]. Despite their small bulk, needle towers have an outsized presence.”

Air Rights

The new developments can be seen as the product of a unique set of circumstances, which have led to an architectural blossoming that will change the New York skyline, but which will be limited to a relatively small number of projects.

“The real cause of these supertall developments is that there is very little land available in prime areas of New York, meaning developers can only find very small plots. At the same time, there are a number of historic buildings in the same areas that do not use the full capacity of their site in terms of height,” says Gregg Pasquarelli, partner at SHoP Architects, which designed 111 West 57th Street for JDS Development Group.

“The ability to transfer air rights to other buildings means owners of the historic buildings can get value out of their rights, and developers who own the small sites can buy up every available square foot to enable them to build tall and take advantage of the views,” he says.

The final key to unlock these projects is the price that people will pay to acquire a view over Central Park. One57 has 90 stories and only 94 apartments, plus a Park Hyatt hotel. In January 2015, the top-floor duplex at One57 sold for $100.47 million—the first New York City apartment property to break the $100 million level. The even more willowy 111 West 57th Street has only 45 apartments in its tower section, some of which will be duplexes and are expected to fetch more than $100 million when sold.

The pricing of these apartments—units in 111 West 57th Street are expected to start at $14 million—means they are aimed squarely at the world’s richest people, the 40,000 people worldwide who are worth more than $100 million each as tallied by WealthInsight, a research company specializing in ultra-high-net-worth and high-net-worth individuals.

Such developments have been particularly popular with buyers from Asia, the home of many high-rise luxury developments. But the developments have appealed to ultra-high-net-worth buyers from all over the world.

Global Precedent

In Sydney, a city that a decade ago had no high-rise luxury apartment buildings, Chinese state-owned developer Greenland Group is building a 771-foot-tall (235 m) residential tower in the central business district. When completed in 2019, it will be the city’s tallest residential building. It is being developed to a higher specification than earlier developments because Greenland wanted to be the market leader in Australia and the building is being marketed primarily to an Asian clientele.

In London, Dalian Wanda is developing the 42-story River Tower near the new U.S. embassy site in Vauxhall. As well as being tall for London, the tower will offer hotel concierge services to its residents—an acknowledgment that many of them will be international buyers with multiple homes, looking for a significant level of service.

Wu is keen not to overstate the Chinese influence: “This luxury market is [composed] of the very affluent buyer, both domestic and foreign. For a majority of foreign buyers, however, and the Chinese are no exception, the motivation to purchase U.S. real estate—be it a needle tower apartment in Manhattan or a mansion in the suburbs—is in large part a need to move some of their wealth to a safe haven. Events such as the recent tumult in the Chinese stock market and the government’s massive intervention only hasten the exit of such monies to places like the U.S.

“Then there is the simple fact of the sheer number of ever-wealthier Chinese. These buyers have become and will continue to be a major force in the U.S. real estate market—not only for residential properties, but [also] for properties of all kinds. Chinese developers are turning up on U.S. shores because they are following their Chinese market here. They also believe that better margins can be had here than in China if developing anew, and better values than in China if [they are] assembling U.S. real estate portfolios. Chinese already find themselves bidding against other Chinese here.”

This story is repeated in gateway cities all across the world. London is perhaps the prime example of a city favored by the global rich, while Sydney and Tokyo also are becoming popular destinations for wealthy immigrants, capital, development, tourists, and investors. All offer large, liquid real estate markets; are top shopping and leisure destinations; and offer security of title for buyers who need to park their wealth somewhere.

New York ranks behind London as the second-most-popular global city for the ultra-wealthy to invest in and is set to claim first place by 2025, according to The Wealth Report 2015, published by global property adviser Knight Frank. Surprisingly, considering the per-unit cost of luxury apartments in New York, it represents better value than London or Hong Kong. Knight Frank estimates that $1 million will buy 366 square feet (34 sq m) of luxury residential space in New York, compared with 226 square feet (21 sq m) in London and 215 square feet (20 sq m) in Hong Kong. New developments may push New York City’s prices up, however.

Nonetheless, the demand from U.S. customers should not be understated. The United States still has more billionaires than anywhere else in the world—a total of 615, according to Forbes. CIM reports that, at 432 Park Avenue, the majority of buyers are U.S. residents, with the others coming from Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.

When it comes to the size and slenderness of needle towers, New York has even outstripped Hong Kong, one of the world’s most land-restricted cities. Due to its floor plate–to–height ratio, 111 West 57th Street is ranked as the world’s most slender building, beating Highcliff, an 828-foot-tall (252 m) apartment block in the Happy Valley neighborhood of Hong Kong. While the United States lags behind Asia in the overall number of skyscrapers being built, New York City is now leading Asia in the development of high-rise residential towers.

It is not just supply and demand that enable such development; technology is important, too. Wu notes, “Needle towers of such heights would not be possible if not for advancements in the development of high-strength concrete [rated at] 10,000 psi, as well as advancements in dampening technology that reduces building sway resulting from wind.”

Writing in Knight Frank’s Tall Towers report, Paul Cohen of U.K.-based consultancy EC Harris notes that construction costs rise not only with height, but also with the building’s slenderness. “The height, shape, and slenderness ratio make tall buildings intrinsically less efficient,” he says. EC Harris estimates that construction cost of the 50th floor of a building will be 43 percent greater on a per-square-foot basis than that for constructing the tenth floor. This inevitably means that such buildings can be viable only in certain markets and on certain sites, where land prices and high demand for luxury residences justify the investment.

However, a number of local residents’ groups and commentators have complained about the new towers coming to Manhattan and the shadows they will throw over Central Park. However, the New York City planning authorities have been amenable to the developments so far. In a letter to community leaders in August, Carl Weisbrod, director of the New York City Department of City Planning, wrote: “Given the important role midtown Manhattan plays in the city’s economy, we have no immediate plans to reduce the current as-of-right density or bulk requirements.

“Midtown Manhattan has always been a high-density, high-bulk area given its concentration of mass transit and its role as the city’s premier business district. . . . Thus, supertall buildings do have the effect of preserving existing height on neighboring sites, which usually means that buildings with different heights and of different eras are much less likely to be demolished. This often leads to a more interesting streetscape and pedestrian experience as well as [resulting] in an incredibly dynamic iconic skyline [that] is the envy of the world.”

A further boost to the projects is that developers are able to afford—and, indeed, need—to build to the highest standards possible. At 111 West 57th Street, SHoP has used terra-cotta and cast bronze to create a luxurious facade and uses the required setbacks for an elegant feathering effect. “We wanted to create something with the elements of a classic New York skyscraper that also utilized modern techniques,” says Pasquarelli from SHoP.

As a global gateway city, New York has the international appeal and the pricing to support the development of needle towers, but will the trend spread to other locations in the United States? Wu says this is inevitable. “San Francisco, Miami, and Boston already have mini–needle towers underway,” he notes. “Other cities such as Seattle and Atlanta will follow.”

Mark Cooper is editor of AsiaProperty magazine.