The port city of Guayaquil is the largest metro area in Ecuador and also the country’s economic core, accounting for about a quarter of its gross domestic product. But its path to prosperity over the years has been anything but linear. For much of the late 20th century, Guayaquil was plagued by cultural degradation and political instability. That changed in 1992, when the country embraced a new development model that made it a recovery blueprint for other cities to follow.

Alina Delgado - a former resident of Guayaquil who took part in the redevelopment and is now an urban planning researcher at K.U. Leuven, in Belgium - chronicles the city’s rise, fall, and rebirth in an upcoming issue of the journal Cities.

“I can see the case of Guayaquil from two points of view: as a common citizen and also as participant of the urban process,” Delgado says. “I thought that a more complete view of the whole process should be given, pointing out the circumstances in which the model was implemented in order to give a more balanced and just overview of the model outcomes.”

Located on the Guayas River, Guayaquil emerged as a critical port city in the late 19th century. In the 1950s, the city experienced a banana boom that led to the formation of a robust central business district. Beginning in the late 1960s, however, Guayaquil began to suffer what proved to be a prolonged period of urban decay. Sprawl pulled the population into the suburbs, businesses fled the core, infrastructure deteriorated - all problems compounded by the city’s political chaos and corruption, as well as the El Niño natural disaster. For roughly three decades, until the early 1990s, Guayaquil was reduced to what Delgado calls in her upcoming paper “a city without citizenship.”

In 1992, the city made a serious attempt to address its problems and reverse its negative momentum. A reorganized municipal government emphasized civic campaigns designed to increase residential connection with the city. A partnership of public and private institutions, guided by the stronger local leadership, implemented a development model that encouraged the improvement of public space. This effort’s chief aim was the renovation of the city’s riverfront area, which became known as the Malecon 2000 project.

Malecon 2000 - which cost roughly $100 million in U.S. dollars - was completed in early 2002. It was funded by a new law that enabled urban Ecuadorians to donate up to 25 percent of tax payments toward the project. The riverfront now boasts an array of cultural attractions that include a shopping center, a cinema, a museum, walking areas, and public gardens. One of the most critical results of Malecon 2000 was the recovery of “pride in the city,” says Delgado, who was part of the project’s design team.

“It was not just about rescuing the city from the physical chaos in which it was, but recovering the self-esteem of its inhabitants - using strong messages recalling the recovery of citizenship, the collective memory of the city, and its former relation with the river,” she says.

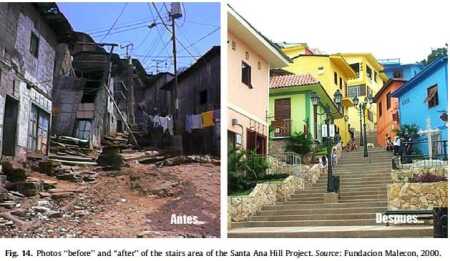

The success of the Malecon 2000 project soon elevated the condition of its surrounding areas. Crime fell 70 percent in the once dangerous neighborhood of Santa Ana Hill, for instance, as an influx of cafes and galleries replaced run-down buildings. A look at Santa Ana Hill before and after its regeneration, from Delgado’s upcoming paper:

Other public infrastructure improvements followed — perhaps none more important than the city’s new bus rapid-transit system, the Metrovia, which began service in 2006. As a result of its impressive rebound, the United Nations named Guayaquil the best-managed city in Latin America in 2004, and for the city’s efforts at improving transportation, Mayor Jaime Nebot received the Sustainable Transport Award from the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy in 2007. Other cities in Ecuador have since replicated Guayaquil’s recovery model, Delgado writes.

That doesn’t mean it’s been perfect. Residents of Guayaquil weren’t always incorporated into the decision-making process, as in the case of Santa Ana Hill’s redevelopment. Crime remains a problem in places, so much so that gated communities have emerged, further segregating higher-income groups. Around 70 percent of city residents can’t cover the cost of basic needs, Delgado reports.

To address these problems, Delgado believes resources from the regenerated areas should be redistributed across the city more evenly. Such a strategy would be the first step toward a more inclusive development approach that would ultimately connect fragmented parts of the city and reduce local tensions, she believes.

“A more balance approach should be given with this respect — recognizing the work of the municipality and private companies that take care of the regeneration and maintenance of those public spaces, but at the same time consulting citizens about those rules and really integrating them as participants in the regeneration process,” she says.

Delgado’s comments, provided via email, have been edited slightly for clarity.

Reprinted with permission from The Atlantic Cities. Copyright 2012 by The Atlantic Monthly Group.