Strapped by student loan debt, stagnant wages, and tighter credit, millennials are having a more difficult time than previous generations buying homes—especially in the walkable, close-in urban neighborhoods that many of them prefer. Economist Jed Kolko calls it the “millennial mismatch—millennials can afford markets where they don’t live, but they can’t afford many of the markets where they do live.”

Now, Mark Schrieber, a millennial architect/developer working in the Miami office of New York–based East End Capital, which has redeveloped warehouses as creative retail space in Miami’s Wynwood neighborhood, has conceived the idea of developing a group of flexible, two-unit urban townhouses in an upward-trending close-in area to make them more affordable to his fellow millennials who want to buy a home.

Elevated Land Costs

The cost and limited availability of land for urban townhouses in such walkable, close-in urban neighborhoods exacerbate the affordability problem. While land in the suburbs and in smaller cities is more affordable, it is apparently less desirable for a substantial segment of millennials. Without substantial relocation, the mismatch of locational demand and supply creates a development problem.

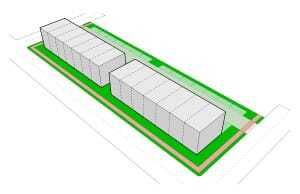

For example, comparables for infill land in Miami that Schrieber found were nearing $40 per square foot ($430 per sq m), equal to $1.6 million per acre ($4 million per ha), which produced a raw land cost of about $76,500 for his 14 townhouses on a 29,000-square-foot (2,700 sq m) site. The site lies in an emerging retail and arts neighborhood at NE 14th Court and NE 72nd Street and has a Walk Score of 87. The site comprises four lots, each measuring 145 feet long by 50 feet wide (44 by 15 m); two of the lots have houses and two are vacant. Miami systems development fees for two-unit townhouses can exceed $16,000, so permitted land costs would be more than $92,500, plus actual utility development and connection costs. With a 10 percent markup for overhead and profit, land costs of about $102,000 would exceed 24 percent of his projected development cost of $410,000 per unit against his projected $477,000 targeted sales price.

Ground-Leased Lots

An important way to ameliorate the land cost problem is to develop the two-unit urban townhouses on fee-simple lots that are retained by the developer and then ground-leased to the buyer. That accomplishes several goals. It lowers the effective sales price for the buyers by 21 percent, the amount of the land cost, here from $477,000 to $375,000. It reduces the downpayments, which are onerous for millennials, few of whom have been able to save enough cash to make large downpayments. With the same 80 percent mortgage on the ground-leased lot, the downpayment would be reduced 21 percent to $75,000 from $95,400, approximately equal to the land cost. The amount to be financed in the mortgage would decline to $300,000, while the loan-to-value amount would decline to only 63 percent, which is significantly more secure for the lender. For the buyer, if the mortgage were a 30-year fixed-rate loan at 4 percent interest, the mortgage constant of 5.73 percent would require monthly payments of just under $1,440.

Of course, the buyer would need to pay ground rent to the developer. If the developer accepted a return of 6 percent on the land cost, the monthly ground rent would be $510. When added to the mortgage payment, the buyer’s monthly cost would be $1,950.

Flexible Two-Unit Urban Townhouses

In addition to ground-leasing, Schrieber attempts to make the townhouses affordable to double-income millennial couples by designing flexible, two-unit urban townhouses of 1,800 square feet (167 sq m). The ground floor is a complete 600-square-foot (56 sq m) one-bedroom, one-bathroom unit, measuring about 18 feet wide by 34 feet long (5.5 m by 10 m). Schrieber estimates that the one-bedroom units would rent for about $1,250 per month. Offset against the $1,950 monthly payments, the net cost to the buyers would be only $700 (plus insurance and tax), which would let them live in a two-bedroom, two-bathroom, 1,200-square-foot (112 sq m), two-floor townhouse, plus penthouse roof deck.

The buyers gain flexibility and economic resilience. They might choose to live in the ground-floor unit and rent out the townhouse for about $2,000. If later they have children or earn higher incomes, they might choose to absorb the first-floor space into one larger unit for themselves, or to keep it separate for use by a nanny. They might choose to have elderly parents live in the first-floor unit, assisting with child care, or being assisted by their children. The buyers could have the option to purchase the land under the townhouse if their incomes increase, or upon resale of the unit. Or, the original buyers could resell the house at a lower price than its competitors since it would be able to exclude the land cost from the resale price. Or the landowner might give the new buyer the option to purchase the land at its cost plus a stipulated percentage increase.

Development Advantages

By charging a lower sales price, and with smaller downpayments required, the developer should be able to increase its absorption rate, thereby reducing its carrying costs. The developer would already have paid for the land and would gain a return on both it and on the sale of the townhouse more quickly. The developer’s income stream would be protected by the house as security for the ground rent.

However, the lender would likely require that the ground lease be subordinated to its first mortgage, which would mean that the developer would insist on a higher return. But since the first mortgage would then be only 63 percent of the market value of the house at the time of first sale, the developer should be protected. If the developer has increased the value of the neighborhood with the development, underlying land and market values should increase the landowner’s margin of security. Moreover, since the developer still holds title to the land, rather than simply a lien, in the event of a default on the ground rent, it might reacquire the townhouse at or below cost.

The developer itself could retain more flexibility than with an outright sale. It might choose to treat the ground rent as a long-term income stream. It might choose to sell the ground lease either to the townhouse owner, or in bulk to a third party. It might retain the land as a means to keep the community well maintained to preserve property values and to protect resale prices of the units, which it could not do under a condominium structure. Buyers could benefit from this protection without the disputes that often arise in a condominium community, or with limited control through a homeowners association.

Lending Advantages

The lender’s position also could be improved from the landowner’s economic interest in preserving the values of the townhouse community it built. The fact that the lender’s loan would be a smaller percentage of the full value of the property, since land would be excluded, might make it willing to finance as much as 85 percent of the $375,000 purchase cost, or $318,750. If that mortgage were a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage at 4 percent, the mortgage constant of 5.73 percent would require a payment of just under $1,750. When added to the $550 ground rent, the buyer’s monthly cost would be $2,300, offset by the $1,250 monthly rental income, a net cost of just over $1,520. More important to the millennial buyer, the downpayment would decrease by $18,750 to $56,250, just under 12 percent of full property value, while the lender’s share is still only 67 percent.

The landowner would be supplying 21 percent of full property value and risks default if the buyer defaults on the mortgage if it is unsubordinated. At a full monthly cost of $2,630 (including 1.5 percent for tax and insurance), assuming that the buyer’s housing cost not exceed 33 percent, buyers would need to have annual incomes of $96,000, therefore suggesting that only double-income millennial couples could be buyers. But here is where the second unit makes it more affordable for the buyers and more secure for the developer: if the first-floor unit actually rents for $1,250 and the buyers’ net cost is really $1,380, the buyers’ income could decline to $50,000 and the buyers would still be able to pay both the mortgage payment and ground rent without paying more than one-third of their income. In most urban markets, the rent of a one-bedroom unit in a walkable urban neighborhood could be $1,000 to $1,500 per month, yielding a net cost of close to $1,300 per month to the millennial buyer.

In addition to lowering the purchase price by 21 percent, if the townhouse is developed as a two-unit duplex building, the buyers’ lenders will be able to consider the potential rent from one of the units in the qualification process. This would be superior to attempting to develop an accessory unit, because secondary-mortgage guidelines from Fannie Mae discourage such units. Fannie will buy loans on properties with legal accessory units only if the value of the legal second unit is relatively insignificant in relation to the total value of the property.

Zoning Challenges

The ground floor is a complete 600-square-foot (56 sq m) one-bedroom, one-bathroom unit, about 18 feet (5.5 m) wide by 34 feet (10 m) long. Schrieber thinks the one-bedroom units would rent for about $1,250 per month. Offset against the $2,200 monthly payments, the net cost to the buyers would be only $950, for which they would get to live in a two-bedroom, two-bathroom, 1,200-square-foot (112 sq m), two-story townhouse with a penthouse roof deck.

From a zoning perspective, Miami’s form-based code, Miami 21, helps somewhat to facilitate this type of dense urban infill. Since rear access is provided via private alley, replatting of the land down to 18-foot-wide (5.5 m) parcels and 1,800-square-foot (176 sq m) lots is permissible.

However, following current zoning definitions strictly, each building would need to be classified as a two-unit multifamily building since the code defines a “duplex” as “two family-housing: Two (2) dwelling units sharing a detached building, each dwelling unit of which provides a residence for a single housekeeping unit.” Schrieber refers to the product type as a “duplex rowhouse,” which he believes should be expressly permitted in most codes without the detached qualification.

Even though Schrieber designed each townhouse lot to accommodate three parking spaces, the Miami code—like many others—imposes minimum requirements for parking spaces and size that complicate such projects. The site lies within a future transit-oriented development (TOD) transit shed that, once in operation, will allow for a 35 percent reduction in the parking requirement. However, if built today, given the parking requirements of 1.5 spaces per unit and Miami’s 23-foot-long (7 m) parallel parking space minimum standard, the spaces along the alley would need to be approved as 18-foot-long (5.5 m) compact spaces.

A cross easement would need to be created to allow for access to the 20-foot-wide (6 m) private alley. This easement could also incorporate a common stormwater system in order to meet stringent stormwater regulations in south Florida. A small maintenance fee would be charged in order to maintain the alley and shared green space between the two groups of townhouses.

Walkable Suburban Application

When applied to inner-ring suburbs, the strategy of developing flexible two-unit urban duplex townhouses not only could make them more affordable to millennial buyers, but also could serve as a way to make such locations denser and more walkable in a way that threatens suburban neighborhoods less than a strategy of adding apartments of equivalent density. Schrieber’s site in Miami comprises only four lots, each measuring 7,250 square feet (674 sq m), a lot size very common in suburbs. The 14 townhouses on the two-thirds-of-an-acre (0.3 ha) site increase the density from six to 21 units per acre (15 to 53 units per ha). But when the first-floor flats are added, the density doubles to 42 units per acre (105 units per ha). While that density exceeds that of most garden apartment projects, the roof-decked townhouses are still only three stories tall—likely no higher than most two-story houses in the neighborhood, and even with pitched roofs are likely not out of scale with the two-story single-family houses in the neighborhood. And 18-foot-wide (5.5 m) lots can accommodate parking for as many as three cars—two behind the house and one parallel to the alley access—while also providing up to 16 on-street parking spaces for guests.

While millennials indicate a preference for walkable urban locations, many may choose suburban locations because of the schools there. Escalating costs of urban housing have meant that larger units that accommodate children are less affordable for families. Smaller enrollments limit the ability of urban school systems to offer the full range of educational opportunities that are more affordable for suburban systems that have growing enrollments. At about 80 million people, the U.S. millennial population is the largest in history. But that cohort covers those in the prime childbearing years and will generate demand for larger units that can house families. In some ways, the large millennial generation will generate its own echo baby boom—one likely to be even more sensitive to economic factors after the Great Recession, stagnant wages, student loan debt, and reduced retirement contributions. Economics and schools could make walkable suburbs more competitive. With lower risks and fees than those in condominium ownership, two-unit townhouses could be an intermediate-density housing type that more of the millennial generation can afford.

Double-income adults with no kids (DINKs) of childbearing age may gravitate to duplex townhouses that have space to accommodate families. Adding first-floor rental units gives them the financial flexibility to afford the space to accommodate children as well as the flexibility to live in the flat or the townhouse, or even the whole house as children age and incomes increase.

Increasing suburban density in this manner can profoundly affect the age diversity of suburbs, especially the older suburbs. The largest segment of the boomer generation still lives in suburbs, but their nests are largely empty. With stairs, townhouses are more likely to attract younger owners. Smaller, first-floor rental flats may attract some boomers who choose to downsize, but the 600-square-foot (56 sq m) ones that Schrieber has designed are more likely to attract younger residents with jobs that are not in the central cities.

The mixture of older and younger residents, and couples and singles, would likely attract restaurants, shops, and services nearby. That would increase the walkability and amenities of the urban locations that millennials have stimulated in close-in urban neighborhoods. And it could be dense enough to support some forms of public transit. To encourage that kind of walkable urban density, suburban cities will need to revise zoning codes to allow multiple types of housing to coexist along with a mixture of restaurant, retail, office, lodging, and entertainment uses nearby. Mixed-use zoning for such housing would need to include small minimum, zero-lot-line, fee-simple duplex townhouse lots, down to 16-foot (5 m) widths, with higher permitted lot coverage and reduced parking requirements.

The development strategy of building groups of flexible two-unit duplex urban townhouses could be an important way to infill select urban sites as well as to increase density in suburbs. A more innovative way to make them affordable to millennials is for developers to retain ground leases on these townhouse lots. Such a dual strategy can lower downpayments for buyers, reduce risk for lenders, and increase profitability for developers.

William P. Macht is a professor of urban planning and development at the Center for Real Estate at Portland State University in Oregon and a development consultant.