University Circle Uptown, a 4.65-acre (1.9 ha) mixed-use project that opened in October 2012, spearheaded by Case Western Reserve University (CWRU), creates a new Uptown mixed-use urban center to unite CWRU, a new Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), the Cleveland Institute of Art, the Cleveland Institute of Music, University Hospitals, the Cleveland Clinic, the Cleveland Orchestra in Severance Hall, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Museum of Natural History, all of which are within walking distance.

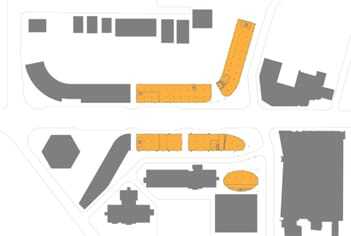

The site plan for Uptown shows in light orange the first phase as the boomerang-shaped Beach Building flanking the northern side of Euclid Avenue and the J-shapedTriangle Building on the southern side. The hexagonal building to its immediatewest is MOCA. Phase II for Uptown will see the development of a diagonal northwest-facing bar of units opposite MOCA and enclosing the southern J-shaped TriangleBuilding. Another J-shaped bar will face it at the west end of the northern BeachBuilding. Both of these new buildings will be twice as tall as the first phase,at eight stories, but will use the same materials.

Five miles (8 km) from downtown Cleveland, University Circle had no commercial hub tying its disparate institutions together. A private university with about 10,000 students on its 100-acre (40 ha) campus, CWRUdecided to give University Circle a heart. It chose to do that by conceiving the project and then selecting both the architect and developer itself. CWRU already had assembled and owned land at the intersection of the main thoroughfare along these institutions, Euclid Avenue, and 115th Street east of Mayfield Road, and would sell or lease to the private developer that it would select.

Many of University Circle’s constituent institutions have sought well-known architects to design their buildings. The Cleveland Art Museum, for instance, has wings designed by Marcel Breuer and Rafael Viñoly. Frank Gehry designed the $61.7 million, 150,000-square-foot (14,000 sq m) Peter Lewis Building at CWRU’s Weatherhead management school with a free-form stainless steel shingled roof. The Cleveland Institute of Art College of Art and Design adaptively uses a former Ford assembly plant that is on the National Register of Historic Places. The Cleveland Clinic master plan was designed by British architect Norman Foster.

MOCA, which also opened in October, is a $27 million, 34,000-square-foot (3,200 sq m) museum designed by Iranian-born architect Farshid Moussavi. It stands as a sculptural monument whose geometric-shaped faceted walls clad in mirrored stainless steel reflect the new adjacent Uptown Center to the east.

CWRU chose architect Reed Kroloff to select a short list of nationally known architects to design the Uptown project while CWRU sought developers to conceive and develop the project. Bloomfield Hills, Michigan–based Jones-Kroloff specializes in design competitions and architect selection and had played a role in finding Moussaui for MOCA and Foster for CWRU campus planning. From four invited developers, Case Western selected MRN Ltd., the development arm of the Maron family–owned companies of Cleveland, which redeveloped the more than 600,000-square-foot (56,000 sq m), $110 million historic mixed-use East Fourth urban neighborhood with shops, restaurants, lofts, and entertainment.

The head of MRN, Rick Maron, had a 34-year-old son in charge of development, Ari Maron, who had taken years of classes at the Cleveland Institute of Music six blocks away. Ari conveyed his team’s dedication to the cultural district by playing a violin solo before the selection committee from CWRU and University Circle Inc. (UCI), which is the nonprofit development, service, and advocacy organization that provides security, transportation administration, and marketing for the growth of University Circle.

Saitowitz’s approach was not only to reestablisha streetscape on Euclid Avenue at a major stopfor the Regional Transportation Authority’s newHealthLine bus rapid transit line, but also tolace both sides of the street with urban plazasand alleys that would penetrate it to connectsurrounding buildings.

Stanley Saitowitz, an architect born and educated in South Africa who is principal of San Francisco-based Stanley Saitowitz/Natoma Architects, is also an architecture professor emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley with international experience in urban planning and infill development. He perceived the architects’ new buildings at the other institutions as object buildings and proposed multiple, linear street-oriented buildings to create a new urban context with which to connect them. His approach was not only to reestablish a streetscape on Euclid Avenue at a major stop for the Regional Transportation Authority’s new HealthLine bus rapid transit line, but also to lace both sides of the street with urban plazas and alleys that would penetrate it to connect surrounding buildings and to the RTA’s new Red Line light-rail station just south of MOCA, which ties together the airport, downtown, and University Circle.

These urban spaces would be lined with restaurants on a pedestrian street called the Alley, reminiscent of East Fourth. Arcades through the southern Triangle Building near its east and west ends, paired arcades near the west end of the northern Beach Building, and near its northern end, enliven the penetrable streetscape. The Alley is scheduled to open in spring 2013 with an additional 10,000 square feet (929 sq m) of food- and entertainment-oriented tenants in the base of the housing towers owned by CWRU. The view from the Alley to the west is terminated by the new MOCA until Uptown Phase II is built, but then an arcade will frame that view.

Panels of extruded aluminum with fine-grained ribs spaced one-half inch (1.3 cm)apart mounted on top of rain screens installed over insulated steel-studded wallsform the skins. But Saitowitz alternates their orientation vertically and horizontallyto give distinctive shading to different parts of the buildings.

Saitowitz expresses his new urbanist sensibilities through very modern structures. Full floor-to-ceiling narrow window bands puncture the facades of the three upper stories of residential units in random patterns and are juxtaposed with horizontal window bands of the same length at varied intervals. This fenestration device lends a sculptural quality to the facades; alternating the skins of each bank of Uptown units reinforces the effect. Panels of extruded aluminum with fine-grained ribs spaced one-half inch (1.3 cm) apart mounted on top of rain screens installed over insulated steel-studded walls form the skins. But he alternates their orientation vertically and horizontally to give distinctive shading to different parts of the buildings as light patterns change during the day, even though the color on the panels is identical.

An important element of the open urbanism of the buildings is that they are kept narrow at 64 feet (19.5 m) wide and that the units are arranged in a linear fashion end to end, not side to side, as is more customary. Each unit is only 26 feet (8 m) deep and its long sides for one-bedroom units range from about 25 to 40 feet (7.7 to 12 m) while its two-bedroom units have roughly 52 feet (16 m) of exterior walls that flood the units with daylight. Even some of the studio units are located in corners and have more than 36 feet (11 m) of exterior walls.

Working with developer Rick Maron on design and construction, Saitowitz sought to increase efficiency and decrease costs to make the rental units feasible without cheapening their appeal. Saitowitz devised an ingenious scheme to place all service functions in an eight-foot-wide (2.4 m) band along the inside walls. These functions include all kitchens, bathrooms, laundries, and closets as well as all plumbing, sprinkling, electrical, lighting, and HVAC mechanical systems in a plenum above the service band. A reveal at the top edge of the plenums creates an indirect light band for general lighting throughout the units while reducing costs. There are no other ceiling fixtures or smoke detectors except for recessed cans in the service areas hidden within the plenum. Sprinkler pipes are also hidden within the reveal area and are side-mounted.

A reveal at the top edge of the service band plenums creates an indirect light bandfor general lighting throughout the units while reducing costs. There are no otherceiling fixtures or smoke detectors except for recessed cans in the service areashidden within the plenum. Sprinkler pipes are also hidden within the reveal areaand are side-mounted. The effect of this device is to reduce the length and costsof utilities required as well as the labor costs for their installation.

The effect of this device is to reduce the length and costs of utilities required as well as the labor costs for their installation. The architectural benefits are to remove the clutter from typical loftlike exposed mechanical systems and to permit unencumbered views through the nearly ten-foot-tall (3 m) spaces. The device also increases development flexibility, allowing for easy reconfiguration of units. Ari Maron says that already changing the demising wall between units easily created a three-bedroom unit and a one-bedroom unit.

Another device brings natural light into those interior service areas. Eight-foot-tall (2.4 m) frosted glass sliding doors enclose the bathrooms, laundry areas, and closets. Most conventional apartment units have windowless bathrooms, whereas these doors bring in shared natural light. In addition, the sliding doors, as well as the pocket doors of living walls, are more space-efficient than swinging doors.

The placement of the service bands against the inside walls also allows for more floor-area flexibility in the layout of the units. Separation of spaces is achieved by placing a single floating wall in the center between the service band and the outside wall, which is flanked by three-foot-wide (0.9 m) floor-to-ceiling pocket doors on each end. This means, for example, that areas on opposite ends of the central living space can create private two-bedroom units, or one might be a quieter area of the living space for a home office.

Finishes for the units are simple and solid. White quartz countertops are installed in white glossy cabinets symmetrically balanced and containing white appliances. The effect is to create a subdued color scheme and neutral palette to accommodate a wide variety of tenants’ furnishings. Concrete ceilings are left exposed because they retain a uniform finish from the four-by-eight-foot (1.2-by-2.4-m) plywood sheets that form the bottom of the post-tensioned concrete floors. Exposing the concrete floors would be more problematic because they need to be sound-insulated from the units below and would require hand finishing, staining, and sealing— all of which add to their cost. Therefore, Saitowitz installed gray-stained, prefinished oak flooring over rigid floor sound insulation.

Parking for the units is also flexible. An urban plaza north of the northern Beach Building, paved with unmarked pervious pavers, can be used for public events. Parking for the Triangle Building on the south side of Euclid Avenue is within an existing parking structure in adjacent buildings owned by CWRU. A transit-oriented area and development, Uptown was designed to achieve a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Silver rating.

The 178,500-square-foot (16,600 sq m) Uptown project faltered twice after MRN’s selection. MRN’s original Uptown partner, Chicago-based Mesirow Financial, withdrew when the economy weakened. Local developer Zaremba Homes, originally slated to build Uptown’s condominiums, withdrew when the recession led banks to refuse to lend on condominium projects. MRN redesigned the project as 114 rental apartments that it solely developed. Studio units measure about 410 square feet (38 sq m) and rent from $875 per month. One-bedroom apartments, with one bathroom, range from $1,325 to $1,990 for 715 to 970 square feet (66 to 90 sq m). Units with two bedrooms and two bathrooms, at 1,110 to 1,330 square feet (103 to 124 sq m), go for $1,825 to $2,260 a month. Twenty percent of the apartments are affordable to households earning up to 80 percent of the area median income.

To fulfill Uptown’s urban retail functions in the first 56,000 square feet (5,200 sq m) on the first floors of the facing four-story structures, the project’s largest tenants are a 16,000-square-foot (1,486 sq m) Constantino’s Market, a full-service grocer, and a two-story, 17,000-square-foot (1,580 sq m) Barnes & Noble, which doubles as CWRU’s bookstore. Food-oriented tenants include a Starbucks inside the bookstore, Jimmy John’s (a Champaign, Illinois–based gourmet sandwich shop chain), Panera Bread, Accent (a pan-Asian restaurant), Chipotle, ABC the Tavern, Mitchell’s Ice Cream, and two other restaurants. Other shops include Anne Van H. Boutique, which is a women’s European fashion clothing store, and Verizon Wireless.

Financing for Uptown consists of multiple layers. The Cleveland Foundation, the country’s fourth-largest community foundation, and the Gund Foundation gave CWRU and UCI low-interest loans and grants totaling $8 million, which were used toward construction. The city of Cleveland extended a $5 million Vacant Properties Initiative loan for construction—45 percent of which is forgivable if it meets certain hiring goals—and spent $2 million to rebuild the Alley. Foundation and city loans feature flexible and nontraditional financing terms, including lower-than-market interest rates and longer-than-standard periods for interest-only payments. The loans are subordinate to first mortgage loans for $17.4 million from Key Bank and First Merit Bank. Cleveland-based Key Bank used a new markets unleveraged loan to write down interest rates. To make the commercial part of the project financeable, CWRU master-leased two-thirds (37,000 square feet [3,437 sq m]) of the 56,000 square feet (5,200 sq m) of storefront retail space, which was used principally for the bookstore through a management contract, and the grocery as anchor tenants, which backstopped the lease payments to support financing.

Enterprise Community Investment, the investment arm of the foundation formed by developer James Rouse, used $10 million in new markets tax credit (NMTC) allocations to help finance Uptown equity from Key Community Development Corporation, an arm of Key Bank. Cleveland Development Advisors provided other NMTC financing through the Cleveland New Markets Investment Fund II, which contributed an additional $6.25 million NMTC allocation. The city of Cleveland and the Village Capital Corporation provided additional subordinate financing. Phase I of Uptown was expected to create 200 construction jobs and 222 full-time equivalent positions after all of its retail tenants had moved in.

NMTC financing was available because, although the prominent cultural, educational, and health care institutions serve middle- and upper-income demographic groups, University Circle lies within two highly distressed census tracts with some of the most underserved and disadvantaged communities in the city, such as Glennville, Wade Park, and Hough, very low-income areas of mostly one- and two-family homes with significant abandonment, vacant lots, and dilapidated structures with limited employment opportunities nearby.

Phase II for Uptown will entail the construction of another J-shaped bar at the west end of the northern Beach Building. In this second phase of development, 44 apartment units and about 20,000 square feet (1,860 sq m) of retail space will be added. There is also a plan for a third phase, consisting of a diagonal northwest-facing bar of condominium units and office space opposite MOCA and enclosing the southern J-shaped Triangle Building, currently planned for retail, office, and housing. Both of these new buildings will be twice as tall as the first phase, up to eight stories, but will use the same materials.

CWRU had owned the south side of Euclid and UCI owned the north side, called the Beach, which CWRU had entered into an agreement with UCI to buy. That contract was assigned to MRN, which closed on Phase I and took fee title. The remaining part of the Beach to the west remains titled in UCI but will also transfer to either CWRU or the developer of Phase II. On the southern side, there originally was to be a ground lease, but with condominiums contemplated on that site the ground lease was thought to be cumbersome and it was converted to a sale of the fee interest to MRN. The plan for condominiums was abandoned after the 2008 crash, but the deal for the land transfer remained intact. The sales of the parcels, for approximately $1 million each, were intended to represent fair market value.

CWRU’s roles as the initiator of the project, the convener of the limited design-development competition, the assembler and initial owner of the land, and the master lessee of the anchor retail spaces at market rents were critical to bringing the project to fruition. Two months after Phase I’s opening in October, the 56,000 square feet (5,200 sq m) of retail space was 100 percent leased, and more than 80 percent of the 114 apartment units were occupied. University Circle’s new urban heart now beats.