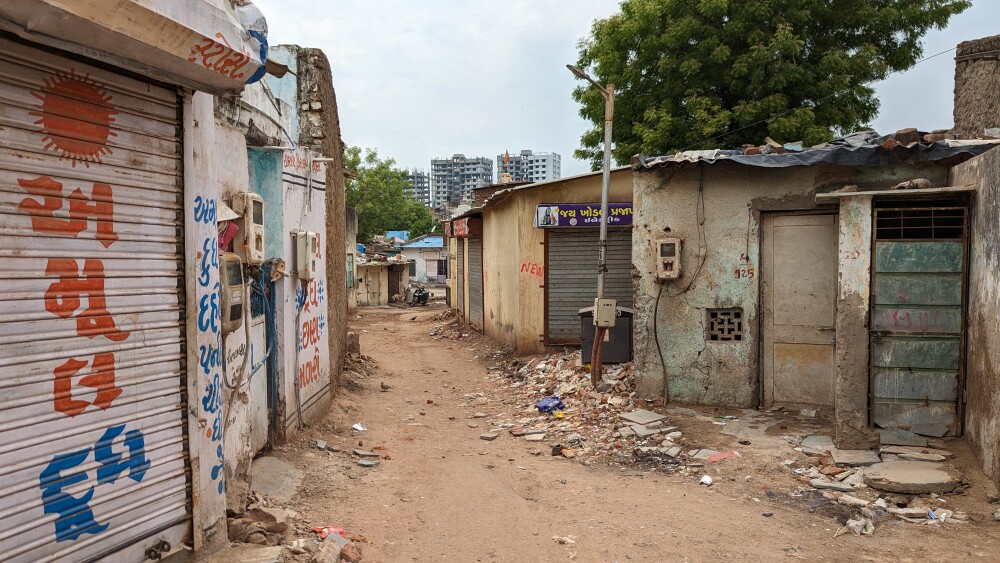

Divyabahen grew up in Ramapir No Tekro, an area of Ahmedabad in northwest India. Labeled a “slum,” it sits on land formally owned by the city. After getting married, Divyabahen lived with her husband’s family for a short time before they looked for a place of their own. Unable to afford to rent or buy a home, they built a small house on public land along a creek near Divayabahen’s childhood home. They enjoyed living under the large shade trees, with space around them and extended family nearby.

In 2023, Divyabahen’s neighborhood in Ramapir No Tekro was demolished to make way for a government redevelopment project. Her extended family scattered into different neighborhoods. Some were eligible for a new apartment, but Divyabahen’s family was not one of them. They did not have electricity records to prove they had lived in the house for more than 10 years. The family now lives in a rented “chawl”—a build-to-rent complex of one-room apartments with shared bathroom facilities—and Divyabahen had to find new schools for her children.

Most of Divyabahen’s time is spent in and around her new home, looking after her daughter and two sons, walking them to school, and picking up groceries from the local shop. Her husband works as a recycling collector and drives a small truck. Divyabahen never had the opportunity to go to school and dreams that her children will be well-educated and find good jobs—something she couldn’t do. She worries about saving enough money for this dream. Most of their meager income is spent on daily needs, with occasional travels to visit relatives in other villages. Any money they manage to save goes toward their children’s education.

What is a “slum”?

Divyabahen’s story is one of a billion. Across the world, 1-in-7 people live in slums, and this figure is anticipated to increase to 1-in-4 by 2030. But how do you picture a “slum”? Overcrowded, dirty, poor, and polluted? Perhaps you are also reminded of places called ghettos, shanty towns, hovels, or favelas.

One of the first published definitions of “slum” in 1812 was synonymous with “racket” or “criminal trade.” Shortly after, this definition took on a spatial meaning to refer to rooms where “low goings-on took place ... inhabited by people of a low class ... [and] loose talk.”

A more recent definition by the United Nations describes a “slum” as having five physical and legal characteristics:

- inadequate access to safe water

- inadequate access to sanitation and other infrastructure

- poor structural quality of housing

- overcrowding

- and insecure residential status

Although the definition has moved past behavior and morals to simply mean poor general living conditions, the negative association of presumed illegality remains. It is not surprising then that our response has been to demolish slums and forcibly evict the residents—sometimes with resettlement to the city outskirts. More recently, there has been some acknowledgement that relocation should try to keep affected residents close to their existing places of work and to their children’s schools.

Slums in the sky

Many of these resettlement projects—primarily high-rise apartment buildings following Le Corbusier’s Radiant City model—instead become “slums in the sky,” where outcomes are often worse than the ground-level original. Studies of slum redevelopment projects in India, for example, have found that high-rise residents experience increased social isolation—a mismatch between lifestyle and building design—and increased costs associated with living in the new building. Over the last seven years, my research has aimed to understand why people want to remain living in areas that outsiders label as inadequate—with “faulty arrangements and designs”—and what features of the built environment actually contribute to their well-being.

Ahmedabad is the largest city in the state of Gujarat, and is home to some 8 million people. Over 728,000 of these residents live in so-called slums, with 60 percent located on private lands and 40 percent on land owned by the city or state. I first visited Ahmedabad in 2016, when I worked as an architect to design a preschool in Ramapir No Tekro, one of the city’s largest informal settlements—a more neutral term referring to a settlement without formal tenure.

I then spent six months over 2017-2018, and two weeks in 2023, immersed in community centers and preschools run by Manav Sadhna to undertake doctoral research on the significance and meaning of architecture in four such settlements across the city. Analyzing these places, I found coherent spatial patterns that contributed to the effective management of privacy, social cohesion, cultural expression, and resource acquisition.

Informal spatial logics

My research revealed that four key design features of the built environment can help improve living conditions in informal settlements like Ramapir No Tekro.

First, homes are located near work, schools, health care and extended family. Second, residents have control over design and construction, upgrading only when affordable, which creates a sense of ownership and invites greater investment in the common areas. It also can help residents to prioritize their spending, such as their children’s education. Third, houses are clustered in groups that connect neighbors. Designs typically feature an entry porch that allows activities from small dwellings to spill into common areas, fostering greater social connection. Finally, neighborhoods have a clear hierarchy and scale of shared spaces: from private homes, to semi-private porches, to semi-public common areas, to public streets. Spending time in shared spaces directly outside the home helps to build strong community bonds.

My research also questioned the common assumption that informal settlements like Ramapir No Tekro are spontaneous, unplanned, and ad hoc. Such views, embedded in policy, can be part of the rationale for slum clearance and relocation, which greatly disrupts the existing social and economic networks that these settlements depend on daily.

A recent article published in the Journal of Architecture I co-authored with Dr. Timothy O’Rourke shows that Ramapir No Tekro was, in fact, built incrementally, and it was planned with architectural intent based on traditional rural housing types. As more and more rural residents migrated into Ramapir No Tekro, it is not surprising that rural building traditions were also imported.

While appearing disorderly to an outsider, the houses I documented in Ahmedabad’s informal settlements follow a formal spatial pattern and logic informed by the residents’ determination to adapt to their environment by using existing architectural traditions.

Language matters

The language we use to discuss poverty, housing, and slums can perpetuate negative stereotypes, stigmatize residents, and have a detrimental impact on interventions that are made. Expressions like “slums,” “urban blight,” or “the underprivileged” can reinforce preconceived ideas about moral failing or hopelessness. They can also obscure both the systemic issues creating such settlements in the first place, and the positive aspects that can lead to effective, resident-led, sustainable solutions.

Eliminating such terminology also helps enclaves such as Ramapir No Tekro to connect to the wider city. While housing design alone cannot change the structural inequality facing “slum” residents, good design can enhance their daily lives. Good design already exists in these settlements, and moving beyond labels and stereotypes can help us find it.

Further reading:

Knowledge Finder: 2024 ULI ASIA PACIFIC HOME ATTAINABILITY INDEX

Urban Land: In Print: Slum Health: From the Cell to the Street