In early August 2011, two new light-rail lines opened in Salt Lake City, one year ahead of schedule and 20 percent under budget. It was a rare success story in a country that has seen funding for transit system expansions walloped by the faltering economy and declining sales tax revenues. What’s behind this effort? In Utah, business leaders—working with political, environmental, and community interests—have helped propel the region’s full-speed-ahead investment in transit and connecting infrastructure.

The two new light-rail lines—the 10.6-mile (17-km) Mid-Jordan extension and the 5.1-mile (8.1-km) West Valley City extension—will nearly double overall mileage in the city’s light-rail network, called TRAX. On opening day, Michael Allegra, general manager of the Utah Transit Authority, said that when the authority bought the rail right-of-way nine years ago, “we figured it was for maybe 2030 or 2040 at the earliest, and never dreamed this would be completed so fast.” Additional projects are underway, including an extension of TRAX to Salt Lake City International Airport in 2013, the extension of the Front Runner commuter rail to Provo in 2014, downtown streetcar lines, and other projects.

The accelerated expansion of the region’s transit system—part of an aggressive $2.4 billion program called FrontLines 2015 that will add 70 miles (112 km) of new rail to the existing system by 2015—was made possible by funding from a variety of sources, including a ballot-approved quarter-cent sales tax increase, federal stimulus money, and contributions from local developers. Kennecott Land, developer of the Daybreak master-planned community in South Jordan, Utah, donated $13?million in land and money toward the Mid-Jordan line, viewing it as a boon to its Daybreak development. Kennecott president Don Whyte said the line will also reduce air pollution: “If we’re really going to have an impact on air quality in Salt Lake County, it’s with projects like this that take cars off the road.”

The success of transit in Utah—an overwhelmingly conservative state—reflects not pie-in-the-sky environmental idealism, but a sober assessment of what it will take for the state’s most populous and economically important region to continue to thrive and grow in the coming decades. Success will depend on the area’s ability to accommodate population growth and spur development while at the same time addressing air quality challenges, conserving water, and preserving and capitalizing on its natural beauty.

The TRAX expansions are one component of a long-term, multifaceted regional investment strategy developed by regional leaders over more than a decade. Business leaders like Whyte have been a critical part of this effort, helping fund important projects and also spearheading efforts to lay out a path for a prosperous, sustainable future for the region. The roots of this initiative go back to the mid-1990s, when leaders—convinced of the need for a comprehensive approach to growth in the region—established a new coalition of public and private forces.

Dubbed Envision Utah, the organization was given the task of developing a long-term growth plan for the ten-county Greater Wasatch Area, which encompasses Salt Lake City and is home to four of every five Utahns. After three years of public involvement, preference research, and the preparation of growth scenarios that helped illuminate the cost implications of continuing on a sprawling and automobile-dependent growth path, Envision Utah finalized its Quality Growth Strategy in 1999. The strategy capitalized on the momentum provided by the opening of Salt Lake City’s first transit line, built to serve visitors and athletes in town for the 2002 Winter Olympics, by providing a blueprint for development of the region that provided for a major expansion of the fledgling transit system and favored dense, mixed-use, and transit-oriented development over continued auto-oriented sprawl.

| The Mid Jordan extension of Salt Lake City’s TRAX light-rail system links Daybreak with the rest of the region. Construction of the line was accelerated by contributions from the developer, Kennecott Land. |

Many regions have smart growth aspirations that have not translated into real action or changes on the ground. But in Salt Lake City, the Quality Growth Strategy has formed the backbone of the region’s plans and infrastructure investments since it was approved. In 1999, the strategy was adopted by Utah’s state legislature, which passed complementary legislation to promote smarter land use and preserve open space. Residents of the Salt Lake City area have approved three sales tax referendums—in 2000, 2006, and 2008—to fund transit construction. Local governments have modified zoning codes and design guidelines to work in harmony with the plan, and mixed-use developments are springing up around new transit stations.

What’s the secret to success in Salt Lake City? At least in part, it is the proactive role that the business community has played in getting behind transit and promoting the kind of development patterns and complementary infrastructure—including sidewalks and bikeways —that make transit work. These leaders were motivated by necessity.

After a 1992 ballot initiative to fund transit failed, the Utah Transit Authority scraped together funding for the region’s first light-rail line. But there was little money to do more. And in the 1990s, local business and political leaders grew alarmed by worrisome trends, including a growing anxiety about the region’s future, as well as politically fractured decision making, both of which were exacerbated by a constrained geography, with habitable areas hemmed in by lakes, mountains, and desert. The result was that residents and businesses were leaving the state, to the detriment of the local economy. Convinced of the need for a new direction, a loose coalition of businesspeople came together to create Envision Utah and plot a better future for the region.

The early leadership of Envision Utah was drawn from the private sector. The founding chair, Robert Grow, was a prominent businessman and president of a local steel mill who believed that “the way we grow has a direct effect on personal and public transportation costs, infrastructure costs, and taxes.” Grow was succeeded by businessman Jon Huntsman, who went on to serve as ambassador to China before becoming a 2012 Republican presidential candidate. Other business leaders involved in the process were drawn from large firms with strong roots in Salt Lake City and the Wasatch Front region.

It takes a village to create a new organization and fund the plans it comes up with, and startup money for Envision Utah came from a variety of public and private sources, including the federal government and local foundations. The organization’s public sector complement is the region’s metropolitan planning organization, the Wasatch Front Regional Council, which represents dozens of local governments but does not include private businesses.

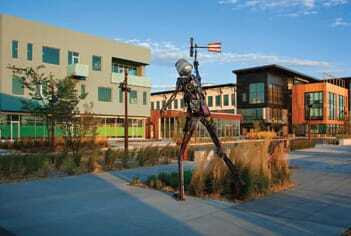

| Art and sculpture liven up public space in Daybreak. |

After completing the regionwide Quality Growth Strategy, Envision Utah shifted its focus to implementation of the strategy and creation of plans for specific geographic areas. One of its largest studies to date is an update to Salt Lake City’s long-term downtown plan, commissioned by the Salt Lake Chamber of Commerce. Downtown Rising, released in March 2007, was the outcome of this process.

Purposely convened by the business community rather than the public sector, the visioning process for Downtown Rising relied on funding and in-kind support from corporations, including banks, newspaper publishers, and real estate developers, as well as the George S. and Dolores Doré Eccles Foundation. George Eccles owned the largest bank in Utah, and along with his wife, Dolores, he envisioned the Eccles Foundation as a way to fund improvements to the environment, health care, the education system, and the arts scene of Utah, all of which are emphasized in plan.

In particular, Downtown Rising noted that local roads, interstate highways, Amtrak rail lines, cross-country bus lines, and local bus and rail lines all converge in the city, and worked to take advantage of the opportunity for the downtown to serve as a multimodal transportation hub. The plan supported the expansion of the TRAX light-rail system, and capitalized on that investment by designating several streets as transit corridors, targeting them for dense, mixed-use development. Other land use interventions include limiting surface parking, reducing building setbacks, adding new ground-floor retail space, and implementing other strategies to encourage new residential and mixed-use development downtown.

For the region, the ambitious TRAX system expansion plans are part of a larger strategy to accommodate one-third of the region’s future development on only 3 percent of its available land. By 2015, it is expected that 70 percent of Utahns will live within three miles (4.8 km) of a major rail station; by 2030, that figure is expected to jump to 90 percent. The Utah Transit Authority, directed by a 15-member board representing the state legislature, the governor, and the cities and counties in which it operates, is responsible for operating and expanding the regional transit system, which includes TRAX light rail, commuter rail, traditional buses, MAX bus rapid transit, and the proposed Sugar House streetcar line.

For Salt Lake City’s business interests, the expansion of the transit and light-rail system serves a number of economic goals. Using modeling comparing the high-quality growth plans to the status quo/business-as-usual investment path, leaders determined that transit will reduce the overall cost of infrastructure paid for with tax dollars (by avoiding the costs of building and maintaining a sprawling network of roads), as well as lower personal transportation costs. By providing additional mode options for workers, the transit system expands access to employment and reduces congestion overall. Finally, it can help stimulate economic activity in the region’s commercial core and open up opportunities for new transit-oriented, mixed-use, and residential development along transit corridors. For Whyte, transit was key. “We knew that a robust transportation network that included TRAX was vital for the full development of Daybreak and the long-term plan of 20,000 rooftops,” he says. “So, figuring out how to make the Mid-Jordan Line a reality years earlier than planned became a key part of our business plan.”

Mitigating climate change impacts, addressing air quality issues, and preserving open space are other important goals. What’s compelling about the Salt Lake City story is the way that private sector leaders put these objectives together with economic and business imperatives to form a strong case for an ambitious and far-reaching expansion of the region’s transit network, and the way that the region has steadfastly gone about pursuing—and accelerating—its transit agenda.

This is the second in a new Urban Land series, “Business on Board,” investigating the business community’s role in advancing transit. To be added to the infrastructure mailing list, e-mail [email protected].

To read other articles in this series, see:

Seattle and Suburbs Find Innovative Compromise to Save TransitNoMa: The Neighborhood That Transit BuiltRegional Transit: Regrouping in the Tampa Bay Area

Healthline Drives Growth in Cleveland