A new generation of green building evaluation mechanisms is gaining popularity in the United States, signaling a new phase in the industry’s engagement with environmental and sustainability issues, one in which simple building certification is no longer enough and the commercial real estate marketplace is increasingly having to negotiate a variety of new building codes, additional ratings systems, and even performance measures.

Indeed, the very success of the U.S. Green Building Council’s (USGBC) Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) rating system has propelled the nonresidential marketplace into a broad debate over how best to define and verify a building’s “greenness.”

A growing contingent of states, from Florida to Oregon, and a handful of cities large and small have adopted the International Green Construction Code as a mandatory green building requirement instead of, or in addition to, voluntary rating systems such as LEED. Also, the U.S. Defense Department—which has been an early adopter of green building programs—is preparing a new construction code aligned with both LEED and the ASHRAE 189.1 code, promulgated by the group formerly known as the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers.

While LEED remains the dominant tool and marquee brand to certify a building’s green design, some niche building-design rating systems are emerging to address perceived shortcomings in LEED. These alternatives range from the Green Building Initiative’s Green Globes, which is advertised as a simpler and less-expensive rating system, to the Living Building Challenge’s certification for zero-utility-energy buildings, the next frontier in energy-efficient, context-sensitive design.

Moreover, with the federal government, commercial property owners, and tenants increasingly interested in a building’s ongoing operating performance in addition to its green design attributes, other performance measurement tools are cropping up, such as EPA’s Building Performance with Energy Star program, the Greenprint Performance Index, and even the next generation of LEED, which is currently under development, incorporates a building-performance section.

“A virtual blizzard of green and sustainability metrics has emerged over the past few years,” says Patricia Connolly, director of global sustainability for RREEF Real Estate, the real estate investment management business of Deutsche Bank, and a member of ULI’s Responsible Property Investment Council. “LEED has been the default standard, and it’s a good place to start. We consider a variety of other green programs to apply economic and green best practices on behalf of our clients. There’s been a lack of standards in the industry to communicate sustainability performance, and from an investment manager’s perspective, we need standard metrics to demonstrate both financial performance and operating efficiency for buildings.”

Judi Schweitzer, a sustainability consultant in California and a vice chair of ULI’s Sustainable Development Council, notes that the choice of which standard to use now depends on the building asset type involved, local regulations, and the green goals being pursued.

“Like LEED, all third-party programs have their application and limitations,” Schweitzer says. “If you are working with the Defense Department or building homes, the measuring stick may be different. It is important to ask the right questions. In real estate, the real question is how do you want to account for sustainability’s additional environmental and social benefits? Do you value performance-based results or are you looking for certification recognition, or both? This is an important and meaningful discussion for all of us to have.”

Proliferating Green Metrics

This broad-based real estate industry discussion, though, is taking several twists and turns. Some real estate leaders believe the proliferation of green building standards and measures now requires better coordination and compatibility.

“You have these different organizations with different structures, and from a practical point of view we don’t want to overburden our development teams, so the more these programs are compatible, the better,” says Kenneth Hubbard, executive vice president of Hines, the international real estate development and investment firm, and a ULI trustee. “You want this information to be rational and useful and consistent.”

With so many choices now, the growing legion of green building evaluation mechanisms is leading to some confusion among green developers, owners, and consultants about whether some of the standards overlap and which third-party program to prioritize.

“The USGBC has done an exceptional job of galvanizing the world about sustainable building,” says Colin Cavill, a multifamily developer and senior vice president of investment services for Colliers International in Atlanta, as well as a member of ULI’s Sustainable Development Council. “But there are more competing interests now, so there is a true dilemma about what’s the best program to follow.”

Defense Department Shift

A series of actions by the federal government in recent months has highlighted this dilemma.

Congress in late December inserted a provision in the newest Defense Department funding bill that severely limits the military’s pursuit of LEED’s highest ratings, Gold and Platinum, in new or renovated facilities. This action was prompted, in part, by a long-simmering dispute in the timber industry over LEED’s treatment of domestic wood products. As a result, the Defense Department’s efforts to achieve the highest LEED ratings remain murky, and it could have repercussions for the rest of the real estate industry.

LEED offers design criteria for construction materials, energy-efficient equipment, water conservation, and air quality, among many things. For a dozen years, LEED has been the leading standard for green buildings, with certification becoming the equivalent of a Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval for sustainable real estate. The number of LEED-certified commercial buildings recently surpassed the 12,000 mark, which dwarfs any other rating system.

The federal government was one of LEED’s early supporters. The U.S. General Services Administration (GSA), the nation’s largest civilian landlord, started designing all its new federal buildings to LEED standards, and the Army and Navy later set LEED Gold as the requirement for their new facilities. Today, by one estimate, 25 percent of LEED-certified buildings are built, renovated, and prepared for the federal government, either by direct federal construction or by construction for federal leases by the private sector.

Now the Defense Department’s fiscal year 2012 funding legislation prohibits the military from spending any money to achieve LEED Gold or Platinum certification unless the department produces a cost/benefit analysis with a demonstrated payback or proves that such certification “imposes no additional costs.” Green building advocates immediately assailed the action for adding another obstacle to pursuing energy efficiency. Bryan Howard, USGBC legislative director, called the provision “irrational and misguided at best” on the organization’s blog.

The Defense Department’s response has been evolving this spring. In February, Katherine Hammack, the Army’s assistant secretary of installations, energy, and environment, commented publicly that Army projects pursuing the Silver level were reaching the Gold standard at no additional cost. But the Naval Facilities Engineering Command will no longer “require LEED Gold or allow LEED Gold to be used” unless contractors pursue the certifications at no cost to the Navy, according to spokesman Whitney DeLoach.

Dorothy Robyn, a deputy undersecretary of defense for installations and environment, told congressional committees in March that her office would be issuing a new mandatory construction code “based heavily on ASHRAE 189.1,” along with continuing to pursue at least LEED Silver certification.

ASHRAE’s 189.1 standard was developed in partnership with the USGBC and is structured similarly to LEED, with categories for sustainable sites, energy efficiency, water use, indoor air quality, and materials and resources, such as use of recycled and renewable products. ASHRAE 189.1 and LEED are intended to complement each other.

But they are different. “The codes tell you what to do, and the certification systems measure how well you’ve done,” says Roger Platt, USGBC senior vice president for global policy, who helped found ULI’s Sustainable Development Council.

Kansas City, Missouri–based construction attorney Chris Cheatham, for one, says he is baffled by how the two are supposed to work in tandem. “Requiring both LEED certification and compliance with a green building code may lead to two problems,” says Cheatham, who also writes the Green Building Law Update blog. “First, obtaining both will result in duplicative costs, particularly on the administrative side. Second, requiring both will likely result in conflicting interpretations. A federal contracting officer may interpret a code one way, while a LEED application reviewer may interpret a similar rating system requirement another way.”

Still, the Defense Department’s proposed shift to ASHRAE could be an important development in real estate. If state and local governments and other institutions follow suit, green standards could be required for more new buildings, thus expanding the entire green industry, says Stuart Kaplow, a Baltimore-based real estate attorney and chair of the USGBC’s Maryland chapter.

Kaplow says that because of its stringent provisions, LEED can realistically target only 25 percent of commercial construction starts. “Making 189.1 an alternate path potentially impacts the other 75 percent of construction that wouldn’t use LEED,” he says. “It could be the most sweeping change to green building since LEED itself.”

Congress’s decision to limit LEED occurred for two main reasons, according to industry and political observers. First, LEED got caught in Washington’s belt-tightening: numerous studies over the years—such as one by CoStar Group researchers in 2008 and another by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers last year—have found that achieving Gold and Platinum certification levels does add to the upfront construction costs of a project.

But the secondary reason was much more surprising: Congress became a battleground in the so-called wood wars.

The Wood Wars

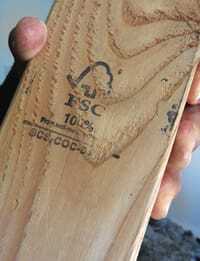

From its beginning, LEED has been aligned with the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), a Germany-based timber association. The USGBC and environmental groups such as the Sierra Club have long viewed the FSC as the most environmentally conscious forest-management standard. The FSC requires, among other things, strong protections for habitats and ecosystems during the harvesting process in order for lumber, flooring, paneling, and other wood products to receive its certification. The only kind of wood awarded points in the LEED certification process is FSC certified.

Meanwhile, the U.S.-based Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI), a group more aligned with timber interests, created its own wood product certification program that also recognizes responsible forestry practices, such as replanting. The SFI’s membership has grown to incorporate nearly 60 million acres (24 million ha) in the United States, almost double the FSC’s roughly 35 million acres (14 million ha). The SFI has used this disparity to its advantage, persuading dozens of governors, members of Congress, and even state foresters to write letters urging LEED to certify and incorporate more U.S.-based wood.

“A lot of politicians care about the wood issue because wood from their own states can’t be counted in the [LEED] credits, and that can hurt their state economies,” says Jason Metnick, SFI senior director for market access.

Then a couple of politically powerful people got involved. U.S. Representative Larry Kissell (D-NC) learned that the U.S. Marine Corps’s Camp Lejeune in his state intended to use imported Asian bamboo for a gymnasium because LEED limited use of domestic wood. He teamed with Senator Roger Wicker (R-MS) to advance the Defense bill’s LEED amendment through the House and Senate.

Still, the USGBC continues to balk at changing its wood policy. LEED’s newest version, which was called LEED 2012 and has been renamed LEED v4, appears to strengthen the FSC’s monopoly in the rating system. Previously, LEED allowed non-FSC wood that was harvested within 500 miles (805 km) of a project; the new version would restrict that area to 50 miles (80 km).

However, the proposed LEED v4—which is still being developed—does provide some accommodation to other woods. Among other things, LEED v4 adds alternative points for conducting an environmental impact study of a product’s life cycle, including planting, harvesting, manufacturing, and distribution. LEED v4 offers points merely for conducting the study itself, no matter the outcome. In fact, there are more points in the LEED system for this study than for using FSC wood, causing the forest council to cry foul. “It seems like a terrible imbalance. It’s not rewarding the right things,” says Corey Brinkema, U.S. president of the FSC.

For the real estate community, wood epitomizes the escalating politicization and polarization of LEED. Some green building advocates see this controversy as a normal give-and-take in LEED’s evolving development process. But others say the controversy is undermining LEED’s image and support.

“More than polemical potshots, many have observed the negative impact the certified wood issue is having on LEED,” says Kaplow.

Additional Standards

Alternatives to LEED have always existed. In fact, the federal government’s creation of the Energy Star energy management standard and the global British Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM) green building rating both predate LEED’s inception in 2000. But because LEED was developed through a broad-based consensus process, it was quickly respected and accepted. Between 2000 and 2010, 400 U.S. cities, counties, states, and federal agencies across 45 states passed some sort of policy requiring LEED standards for their new or renovated facilities.

In the past two years, however, the number of new government entities adopting LEED policies has fallen to a trickle, according to a list compiled by the USGBC. Instead, a growing collection of alternative programs is gaining momentum.

There are green building codes, such as the two-year-old International Green Construction Code, developed by the International Code Council, a U.S.-based construction industry association, and the 2010 California Green Building Standards Code (CALGreen). There are other voluntary building design rating systems, such as the three-year-old Sustainability Tracking, Assessment, and Rating System (STARS), developed by the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE) just for colleges and universities. And there are building operations performance measurements, such as the federal government’s leadership in constructing and encouraging construction of commercial buildings to achieve net-zero energy use off the utility grid.

All this is happening because LEED and Energy Star are no longer enough for a marketplace yearning for more ways to go green and incorporate sustainability. In a report this spring, the GSA compared green rating systems and found Green Globes aligned better with federal requirements for new construction, whereas LEED was most compatible for existing building rehabs. LEED has expanded its leadership role over the years, adding separate certifications for different construction types, from commercial interiors to school facilities. But commercial real estate owners, developers, and tenants now have more choices, and they are seeking additional ways to enhance value and create a competitive advantage.

LEED is here to stay; it is too well established in the marketplace to fade away. Plus, the growth of alternative green codes may turn out to be a good thing for LEED: if more buildings follow green construction standards, then reaching LEED will not be much more of a jump, so more developers may do it. “It makes LEED more cost-effective for those wanting to demonstrate leadership,” says Platt, USGBC senior vice president.

“I’m hearing two things from people in commercial building,” adds Andrew Gowder, Jr., a land use attorney in Charleston, South Carolina, and assistant chairman of ULI’s Sustainable Development Council. “One is, LEED continues to have a very strong brand appeal, and there’s a feeling it’s necessary to some extent to market a building.

“On the other side, others—particularly on the public or institutional side—are looking at the cost of the [LEED] process, and they’re trying to emulate those standards without going through the certification process. . . . So some people may look at more alternatives, but I don’t see a great migration away from LEED.”