This article appeared in the Summer issue of Urban Land on page 71.

Nestled at the tip of Cape Cod, Provincetown, Massachusetts, has a year-round population of 2,500 that swells into the tens of thousands during the summer. Though primarily known as an artists’ resort nowadays, the coastal town—founded some 300 years ago—still retains a bit of its legendary fishing character, with $8 million to $10 million worth of shellfish (lobsters, scallops, and crab) coming across the commercial pier each season.

But Provincetown is facing an uncertain future. Starting in January 2018, the town experienced three 40-year storms (a 40-year storm has a 1-in-40 chance of occurring in a year) over the course of four months. “A new normal was established—that when there was a storm on a full moon at a high tide, the risk of moderate to major flooding was highly probable,” explains David Panagore, Provincetown’s town manager. “Flooding is no longer a potential but an actual. For now, folks have made the needed repairs and improvements. Whether this continues remains to be seen, but it just raises the price point, and those with the funds will pay to keep their property as it is. Along the shoreline of the Outer Cape, there are particular properties that are at risk or becoming at risk of falling into the ocean.”

Provincetown, once known for its fishing industry but now known as America’s oldest continuous art colony and a resort town, experienced three 40-year storms (a 40-year event has a 1-in-40 chance of occurring in a year) over four months last year. When a storm occurs during a full moon at a high tide, moderate to major flooding is highly probable. (Town of Provincetown)

More frequent flooding is but one of the increasing instances of severe weather—dangerous meteorological phenomena including excessive precipitation, wildfires, thunderstorms, tornadoes, hurricanes, cyclones, and floods with the potential to cause damage, serious social disruption, and loss of human life—facing coastal communities throughout the United States. “Two years ago, climate change was a concern we were working on with long-term goals,” Panagore says. “Now, we are the forefront of change.”

Severe weather cost the United States an estimated $91 billion in 2018, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Some 80 percent of that total was the result of just three events: Hurricane Michael in Florida, Hurricane Florence in the Carolinas, and wildfires in the West, primarily California. This is on top of losses in 2017, when Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria battered American shores along with wildfires in the West, resulting in hundreds of billions of dollars in damages.

Officials are acutely aware of the risks associated with increasingly harsh storms, rising sea levels, wildfires, and other incidents. After nearly every event, the scenario is usually the same: fingers are pointed, property owners and insurance companies shell out money for repairs, and calls for changes in development are heard. But finding the political will to meaningfully trade off additional construction for more protection from natural disasters is proving elusive.

“Measures like stronger building codes have been enacted after major hurricanes such as Andrew in Miami and Harvey in Houston,” says Adam Kamins, director at West Chester, Pennsylvania–based Moody’s Analytics. “That said, a broader reckoning that would involve reducing development along coasts, floodplains, and in areas that are vulnerable to fires has yet to materialize. Given the amount of money at stake when it comes to waterfront properties or the unaffordability of California’s coastal cities driving more development inland toward areas that are subject to fires, I don’t expect building patterns to change meaningfully—at least not in the near term.”

In some coastal areas, developers, designers, and architects are taking the risk of severe weather events into account during planning. “Climate change continues to be a significant concern,” says Lou Vasquez, cofounder of BUILD, a real estate development company in San Francisco specializing in mixed-use residential development. “Nongovernmental organizations [NGOs] and governments are working closely together to prepare our region for climate change and to ensure we are planning future communities and developments with climate change in mind. The wildfires in the state have increased demand to replace lost housing, exacerbating the construction resource shortage, especially labor. This has further driven construction costs up and created an even greater squeeze in an already tight housing market.”

Cognizant of the increasing frequency of severe weather along the East Coast, the $600 million Eastern Wharf—a joint venture between Boston-based ELV Associates and Mariner Group and Regent Partners, both of Atlanta—was designed with an eye toward potential severe weather. One of Savannah, Georgia’s most expansive developments—Eastern Wharf’s first phase, which broke ground in October 2018—is expected to include 306 luxury apartments; a 193-room boutique hotel; some 40,000 square feet (3,700 sq m) devoted to retail, food, and beverage uses; and 80,000 square feet (7,400 sq m) of class A office space.

“Our development is not on top of the bluff, but instead down at the river level,” Reid Freeman, president of Regent Partners, says. “Our project is not directly on the coast, so we are not as susceptible to the severe weather. The flood elevation is at nine feet [2.7 m] and the Savannah River is still affected by the tides at our site. We have elevated the building sites and road systems at Eastern Wharf to be well above the flood elevation. Savannah has the protection of the barrier islands as well as the city’s position along the East Coast. Savannah is further west than, say, Charleston or even Daytona Beach. These two factors have spared much of Savannah when severe weather moves through the region.”

Savannah has experienced two significant storms in the last three years, neither of which caused any serious destruction, says Freeman. “Eastern Wharf has experienced zero damage,” he adds. “But now, you must consider not only the costs to build, but also the cost to insure real estate before jumping into the market.”

In other areas, severe weather is considered a fact of life. Although their strength might be increasing, hurricanes are not a new phenomenon in the U.S. Southeast, explains Steve Alger, vice president at the Jackson Companies, a family-owned recreation, resort, and real estate development company in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. “Weather patterns are continually changing,” he continues. “Back in the late 1990s, we had back-to-back hurricanes [Floyd and Dennis] in the Carolinas. Beyond the resulting damage, the outcome was an increase in insurance premiums for properties proximate to the coastline. No one thought much of it, other than the prospect of ongoing increased insurance premiums. So I am not sure we are actually having more severe weather now than we did in the past. What I am sure of is that we have allowed development to occur in coastal areas where oceanside and creekside homes can be and are damaged by storms due to their immediate physical proximity to water. The same can be said where development has been allowed to occur in mountainous coastal areas, such as in California, where homes have been developed in highly forested, very erodible mountainous areas overlooking the ocean. In either of these two examples, improper land use planning has been allowed to occur.”

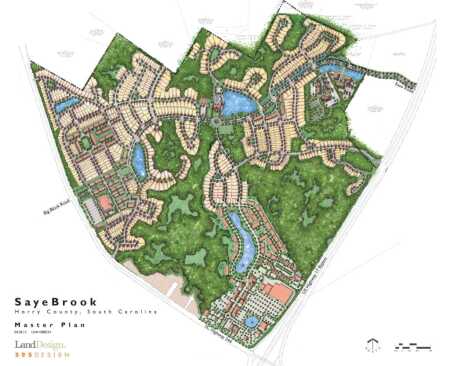

The Jackson Companies is developing SayeBrook, a 700-acre (283 ha) traditional neighborhood development in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, incorporating residential, office, medical, educational, and civic uses. The project also includes the SayeBrook Town Center, a retail lifestyle center, with over 205,000 square feet (19,000 sq m) of existing retail space with national retailers and the new Socastee Middle School. Construction began in 2002 and is expected to be completed in 2035. (The Jackson Companies)

Massachusetts

Severe weather has had a smaller impact on the Boston metropolitan area than nationally. The area has not been hit by the hurricanes and wildfires that have wreaked havoc in other parts of the country, points out Marc Korobkin, associate economist at Moody’s Analytics.

“While the housing market lost momentum in 2018, its recent weakness cannot be attributed to severe weather,” Korobkin says. “House price gains, while still much faster than wage growth, have decelerated as unfavorable provisions in the new federal tax law have made it less attractive to own a home. In addition, home sales are falling in the city, as they are nationally, due to a low inventory of existing homes on the market.”

Boston remains a top performer in the Northeast in terms of employment and income growth. Strength in the large tech and health care industries is key. The labor market is tight, with the jobless rate recently falling below 3 percent—its lowest since the tech boom of the late 1990s and early 2000s. In the short and medium terms, the most pressing challenge for the housing market is likely to be zoning regulations that limit high-density development and drive up house prices and living costs, Korobkin says.

Two years ago, severe weather in Provincetown was a long-term concern. Now, says Town Manager David Panagore, “we are the forefront of change.” In the lower-lying and flood-prone areas along the shoreline, basements of homes and businesses are being reinforced and modified to prepare for potential flooding. (Town of Provincetown)

In Provincetown, the real estate market is proving resilient so far, despite concern about the total additional cost—such as the cost of lifting up structures—brought on by severe weather. Panagore notes that FEMA (the Federal Emergency Management Agency) now mandates that buildings in floodplains be lifted up if any rehab exceeding 50 percent of the assessed building value is undertaken. “When that is factored in, the price point goes up,” he adds. “Along the shoreline, in the lower-lying and flood-prone areas, basements are being reenforced, from the exterior walls to interior sump pumps and other modifications to prepare for potential flooding. Individual owners had put in place various seawalls, and such reinforcements protected many properties from recent events, but what was prudence by a few is becoming necessary for others in our four or five low-lying shoreline areas.”

Adding to that burden is the fact that approximately 600 homes not only are in the region’s floodplain, but also are included in the town’s historic district. “The issue today is how to meet both FEMA and historic guidelines,” Panagore says. “We are working through that as these homes all eventually need to be lifted six feet [1.8 m] on average. Some rehabs are taking a year longer to permit due to managing the overlap and conflict between historic regulations and the impact of climate change. In this regard, insurance—while not yet a problem—is a challenge as home-by-home or commercial property-by-property renovations occur.”

The Carolinas

While the human impact from Hurricane Florence last year was substantial in North Carolina, the economic effects were largely temporary. “Wilmington, where landfall occurred, bore the most severe economic impact, with total payrolls declining by more than 5 percent in September 2018,” says Dante DeAntonio, an economist at Moody’s. “However, the majority of employment losses were recouped during the 2018 fourth quarter across all impacted areas in North Carolina, with leisure/hospitality being one area where the recovery has been a bit slower.”

The most substantial impact from coastal storms is typically the resulting property damage. Some areas that were particularly hard hit by flooding from Hurricane Florence, such as Wilmington and New Bern, North Carolina, also have some of the lowest rates of flood insurance enrollments among coastal areas in the state.

“Lack of insurance coverage makes rebuilding efforts slower and sometimes impractical,” DeAntonio says. “Despite this, building activity recovered quickly in last year’s fourth quarter for those areas that were hardest hit. Dare County, which encompasses most of the Outer Banks and was largely spared from Florence’s damage, has seen minimal change in building patterns as a result of recent major storms. The Outer Banks area, along with tourist destinations in the far southern coast of North Carolina, are protected by much higher rates of flood insurance coverage, which contributes to an apparent lack of deference to increasing storm threats.”

Primarily because of flooding, Hurricane Florence—one of the wettest tropical cyclones recorded in the Carolinas—caused significant damage in and around the Wilmington Metropolitan Statistical Area, reports Jim Henry, vice president of operations at Newland Communities’ RiverLights, a 1,400-acre (567 ha) master-planned community on the shores of the Cape Fear River in Wilmington.

“In the Coastal Carolinas, we’re used to havoc from hurricanes and while you can’t predict the impact from any given storm, you can be prepared for it,” Henry says. “One of RiverLights’ amenities is a 40-acre [16 ha] freshwater lake tied into our well system. A week out from Florence’s expected touchdown, we pumped the lake down by 30 inches [76 cm] to make room for the new rainfall and activated our preparedness plan to secure the site. We made sure all our risk management and insurance plans also were up to date. We had an assessment team ready to enter the community when it was safe to do so to assess damage, line up contractors, and work with the insurance adjustors.”

Newland’s preparations began even before the homes were built, he adds. “Building codes are more intense here, so we build to withstand winds of 130 mph [209 kph],” says Henry. “No glass is entirely break-proof, but the American Architectural Manufacturers Association has a Design Pressure [DP] rating that identifies the load that a product is rated to withstand in pounds per square foot [psf]. The windows in most of our homes have a minimum DP rating of 50—higher than what you might see elsewhere. We also use metal plates at joints in the roof for reinforcement rather than just nail the rafters. The two-car garages have a threaded rod set in concrete that ties the corners of the garage to the roof structure. While it doesn’t make the structure hurricane-proof, it helps to keep the roof on.”

Hurricane Florence also had an acute but short-term impact on home sales. “Did it affect our sales in the 2018 fourth quarter? Absolutely,” says Henry. “But with our quick cleanup and rapid recovery, our sales in January of this year were almost back to normal levels. I think people come and see that the place doesn’t look as bad as they thought and buy a home. People still want the attributes of living along the coast.”

Despite severe weather disruptions, the costal metro areas in South Carolina remain on a tear, says Michael Ferlez, an analytics economist at Moody’s. “Myrtle Beach–Conway–North Myrtle Beach and Hilton Head Island–Bluffton–Beaufort were South Carolina’s two top-performing metro areas in 2018 and will remain at the vanguard of the state’s expansion this year,” he says. “Rising U.S. disposable income continues to attract millions of tourists annually. This, combined with a rapidly expanding population driven by in-migration, will support strong gains in consumer services. Although home construction in the state’s coastal metro areas has moderated in recent months, strength in tourism and a rapidly expanding population will encourage more residential and nonresidential building.”

Despite severe weather, homebuyers continue to be attracted to—and are willing to pay for—premium views and water amenities. “It’s what people aspire to achieve,” says Alger of the Jackson Companies. “Highly desirable properties on the water and coasts will always be in demand. But the ongoing operating cost of owning these properties will rise due to excessively high insurance premiums, ever-rising maintenance and replacement costs, and the increased cost of property management services where expensive homes may be within access-controlled communities in coastal areas.”

In some cases in which the U.S. government has provided flood insurance coverage continuously to owners with properties in low-lying areas, the government either has raised premiums to the point that some owners can’t afford to rebuild and insure again or it has simply refused to offer insurance—thereby ending new development in that area, Alger says.

“This is a good thing—good land-planning changes driven by economics,” he continues. “Most of the sensational events we have seen in recent years are due mostly to improper land use planning as a result of our ever-expanding population of 320 million people in the U.S. Homes should not be built on dunes adjacent to the ocean unless people want to bear the wrath of whatever storms occur. Development should not occur within forested cliffside areas where governments restrict managed timbering that would lessen the creation of fuel for fires—unless these residents want to live with the terrible outcomes we have seen in recent years.”

Severe weather has not affected hospitality transactions. SCG Hospitality purchased the 362-room Vinoy Renaissance Resort and Golf Club in downtown St. Petersburg, Florida, from RLJ Lodging Trust. The Plasencia Group represented SCG Hospitality in the August 2018 transaction and continues to serve as a representative of the owner. The Vinoy will continue to be managed by Marriott under a long-term agreement.

Florida

Florida’s Panhandle bore the brunt of Hurricane Michael—a storm that intensified from a Category 1 storm to a Category 5 storm in 24 hours before slamming into the area last October. Michael recorded the strongest winds since Hurricane Andrew made landfall in 1992.

“Panama City was hit hard by Hurricane Michael in October,” says Maria Cosma, associate economist at Moody’s. “Total employment contracted by 2 percent from September to December—the most of any Florida metro area—and caused a spike in unemployment. The hardest-hit industries were retail, health care, and local government as the storm battered stores, medical facilities, and schools. Military payrolls were also down; damage to Tyndall Air Force Base led to evacuations and reassignments.”

Panama City is still recovering from Hurricane Michael. “Insured losses in Florida totaled $4.7 billion, with the most claims filed in Bay County [which includes Panama City] as the storm leveled homes and commercial properties,” Cosma says. “Private insurers and FEMA are still working to rebuild in the wake of the storm. Congress passed temporary disaster relief funding, but delays in receiving the relief package likely contributed to the hefty economic toll of the storm.”

Florida has one of the strictest building codes in the country, implemented in the wake of Hurricane Andrew, and this is expected to lead to very different residential construction in Panama City. “Most of the homes in Hurricane Michael’s wake were older and many of them were built before the stricter building codes were implemented,” Cosma says. “Homes in floodplains facing damage repair costs above a certain threshold will have to be rebuilt to meet the stricter codes. Of course, meeting these stricter building codes will raise building costs, putting upward pressure on house prices. It may be too soon to tell how Hurricane Michael is affecting the housing market in Panama City. We expect a significant pick-up in single-family homebuilding in 2019 and 2020 in Panama City and hold roughly flat in Crestview and Pensacola.”

Despite the severe weather, Florida remains as hot as it has ever been, and we’re not referring to climate,” says Lou Plasencia, CEO of the Plasencia Group, a Tampa-based national hospitality sales, investment consulting, and advisory firm. “Transaction activity was very strong in 2018 and is anticipated to be robust again this year, especially along the beaches and in urban markets. We expect to see very little slowdown. Areas recently affected by hurricanes, namely the Florida Keys and Southeast Florida, are back to normal with virtually all hotel rooms back in service—maybe even stronger, we would argue, than before. The state has proven its resilience to major weather events and has taken steps to preplan its reaction to and recovery from strong hurricanes.”

Plasencia says that he has not seen any letup in the pace of new construction. “The impact has instead been on the cost of construction since many contractors and their subcontractors have been lured to areas in need of storm-related repairs,” he explains. “These events have also resulted in higher construction costs. We have not seen any meaningful shift in the use of stronger and vastly improved construction materials since Hurricane Andrew in August 1992.”

The Plasencia Group represented the seller, an affiliate of Fillmore Capital Partners, in the sale of the 261-room, 12-story Courtyard Fort Lauderdale Beach in 2017. The buyer was Summit Hotel Properties. Formerly the Oceanfront Hotel, the property closed in 2005 after sustaining damage from Hurricane Wilma. The new Courtyard opened in October 2007 and underwent a $5 million renovation in 2014.

So far, at least some real estate investors seem unconcerned about the severe weather the United States has been experiencing. “No one has commented that there has been any increase in the frequency of natural disasters, and we have seen no serious reaction by institutional or private investors,” Plasencia says. “In fact, these events have often attracted investors seeking to acquire affected properties, perhaps at a discount.”

California

Severe weather and natural disasters—particularly droughts and wildfires—are a persistent concern in California. The Los Angeles metro area saw its share of fires in 2018, but the economy was largely unscathed, says Laura Ratz, an economist at Moody’s. Compared with the Camp fire, which raged in the northern part of the state, the Woolsey fire in Los Angeles and Ventura counties was less destructive in terms of acreage and the number of structures affected.

Above and below: BUILD took into account the threat of rising seas in designing its proposed development at India Basin in San Francisco. The project, which was entitled in late 2018, will have 150,000 square feet (14,000 sq m) of commercial space and 1,575 units of housing—25 percent of which will be affordable—as well as several acres of parks and public spaces. Infrastructure construction is expected to begin in early 2021. (BUILD)

“Rebuilding provides a boost to economic activity in affected regions in subsequent months,” she adds. “Economies hit by major natural disasters are generally made whole again, particularly given the federal and insurance money that flows into the areas. New infrastructure will replace old and outdated infrastructure, improving the capital stock. Among the greatest threats to the outlook is that more frequent and destructive fires and droughts could erode population growth, which is already slowing statewide.

Above and below: O&M, a 116-unit multifamily project of San Francisco multifamily real estate developer BUILD in the city’s Dogpatch District, consists of two architecturally distinct but integrated buildings separated by a publicly accessible midblock courtyard. The O Building on the southern side of the site, designed by Pfau Long Architecture, is organized around a central courtyard and features a dramatic two-story “porthole” opening in the front facade. On the northern side of the site, the M Building, designed by Kennerly Architecture, is organized around a series of private, landscaped courtyards. The project was completed in 2017. CMG Landscape Architects designed the Dogpatch Arts Plaza. (Daniel Gaines Photography, BUILD)

“Residential construction in California is rising at a steady clip, although Los Angeles is a laggard,” Ratz says. “This is likely more the result of land constraints, high costs, and slower population growth than developers’ concerns about natural disasters. Prices are rising faster than the national average, but deceleration is evident in places like San Diego. Home sales have faltered somewhat in recent months, particularly in parts of Southern California. Wildfires probably helped to pull down sales statewide in last year.”

Rising sea levels are another worry that many developers, builders, and architects are taking seriously. Increasing sea levels were a major consideration in BUILD’s proposed development at India Basin in San Francisco. The project will have 150,000 square feet (14,000 sq m) of commercial space and 1,575 units of housing—25 percent of which would be affordable—and several acres of parks and public spaces. Designers took rising sea levels into account. “No one wants to build something that will be obsolete in 10 years,” Vasquez says. “We’re all building with a 100-year horizon.”

While few expect severe weather events to slow in the months ahead, most in the real estate sector are aware of the challenges such events pose. But change occurs slowly. In addition, coastal real estate continues to be extremely popular—a highly desirable amenity that is unlikely to be scaled back significantly any time soon. In fact, there may be even more demand for properties along the water. The Blue Gym Initiative, a 2009 study in the United Kingdom that sought to explore whether blue space environments might be positively related to human health and well-being, found that individuals living near the coast are generally healthier and happier than those living inland.