An infill project configures the street grid to connect to nearby museums and surrounding uses so it can flexibly mix offices, retail space, hotel space, and housing.

| The front door of Museum Place is at the Six Points intersection of Seventh Street and Camp Bowie Boulevard. |

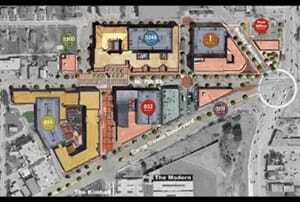

Large-scale infill developments outside the downtown core often can be insular and inward looking, akin to a suburban retail center. It would have been easy to follow such an inward-oriented pattern on an 11-acre (4.5 ha) site assembled in the Fort Worth, Texas, cultural district. But Museum Place, a 1.05 million-square-foot (103,000 sq m) development, is designed to knit 11 new structures into a finer-grained urban fabric of streets that once housed an active mix of shops, restaurants, and community services.

Museum Place is located north of the large superblocks containing the Amon Carter Museum, designed in 1961 by Philip Johnson; the Kimbell Art Museum, designed in 1972 by Louis Kahn; and the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, designed in 2002 by Tadao Ando.

Including flexibility in mixed-use urban infill projects built in phases in challenging markets requires creative responses to building design for multiple uses, functional urban street layouts, and solutions allowing shared parking.

Street Solutions

To create a framework for a mixture of uses that could be developed in phases, Dallas-based JHP Architecture/Urban Design reinforced the historic street pattern and restored it to its orthogonal form. A portion of Sixth Street was converted from a private driveway back into a through-street, and Arch Adams Street was transformed from a meandering lane into a straight, north–south urban-scaled street with special pavement.

| Parking solutions reinforced the smaller-scaled street grid. |

Each street, designed to accommodate as much parking as possible to maximize shared parking available for retail and restaurant patrons, has parallel, diagonal, or perpendicular parking. Seventh Street, the main thoroughfare to the cultural district from downtown Fort Worth 1.75 miles (2.8 km) to the east, was narrowed from four to two lanes with head-in diagonal parking. Diagonal parking was also added on the north side of the four-lane Camp Bowie Boulevard (divided by a tree-lined median), which is the southern boundary of Museum Place across from the museums. The diagonal parking helps slow traffic, and the presence of on-street parking helps activate the streets to support the shops and restaurants.

Rather than being built at the periphery and focused inward on a center court, the parking structures were integrated into the centers of blocks and wrapped with housing, retail space, and offices. The 270-foot (82 m) width of the Fort Worth blocks in that location still permitted efficient, mostly double-loaded housing and office corridors. This is different from what is often the case in mixed-use projects: parking is often placed under buildings, driving the configuration of the uses above because the layout of columns and drive aisles cannot be changed, so the bay spacing of the uses above follows the parking plans. At the same time, fire separation and ventilation requirements can increase the cost and complexity of buildings built over parking.

Courtyards and Shared Parking

| The development’s edges are defined by the culturally and architecturally significant museums to the south. |

At Museum Place, courtyards separate the housing and office space from the parking structures to simplify each structure and lower its cost. Tenants can drive to the level on which their unit is situated and walk across a bridge directly to their floor, avoiding elevators for most of their trips. Separation allows at-grade access to the rear of buildings, which will facilitate conversion of retail space to live/work or residential uses should the market require it in times of recession.

Mixing uses horizontally can still provide the option of shared parking, which can reduce required parking ratios. Museum Place uses planned parking ratios at only two per 1,000 square feet (21 per 1,000 sq m) of office space. Retail space and restaurants were planned at a high 5-to-1 parking ratio, resulting in 700 spaces, but the large number of shared on-street parking spaces throughout the project makes the on-street option more efficient and convenient than some of the structured parking.

With such a high parking ratio, if the retail space does not lease as expected, it could be viewed as desirable office space with more parking than its competition. Hotel parking for 120 units was planned at 1.1 spaces per unit, and the hotel can easily share spaces with the 130,000 square feet (12,000 sq m) of office space in two buildings in the project, for which there are at least 260 parking spaces. In total, there are more than 1,800 parking spaces in the four parking structures, with two having 470 spaces each, one 600, and the fourth, 280.

The lion’s share of that parking is for the 500 rental apartments and 40 condominiums planned at a parking ratio of two per unit. This residential parking is not shared and has access restricted to unit owners and tenants. It is allocated from the top of the garage downward; lower levels are reserved for the office and retail users and the public. Controlled access for payment at the public levels is provided, but will not be instituted initially.

Integrated Urban Design

| |

The front door of Museum Place is at the Six Points intersection at Seventh Street and Camp Bowie Boulevard, but its heart is a T-shaped linear civic plaza at the intersection of Seventh Street and Arch Adams Street. Although this is a public right-of-way, landscape elements and street pavers define a large pedestrian plaza, and the street can be blocked off to create a wholly pedestrian plaza for special events. The individual projects at Museum Place lead to this civic space, and its northern edge is slated to accommodate restaurants with outdoor seating.

Informed by the city’s creation of cultural district design guidelines, its new mixed-use zoning criteria, and the general market interest in mixed-use development, the urban design concept was to approach each block as an expression of its particular place in the development and the mix of uses while linking individual buildings and blocks to one another through shared streetscape standards and building materials. Each block’s geometry, overall massing, and uses were planned as a response to zoning, proposed street hierarchy and streetscapes, neighboring uses, and market demand for various uses.

The development’s edges are defined by the culturally and architecturally significant museums to the south; a redeveloping retail corridor to the east, which continues to the city’s central business district; an older community of single-family homes in the Arts and Crafts style to the north; and a smaller neighborhood retail corridor to the west.

A key element of Fort Worth’s urban design is the nine-mile-long (14.5 km) Camp Bowie arterial boulevard traversing the Arlington Heights neighborhood along a northeast–southwest axis separating Museum Place from the neighboring museums. The boulevard itself is a physical barrier reinforced by the large reflecting pool that surrounds the north side of the Modern Art Museum more than 115 yards (105 m) to the south.

In the vertical design of 3131 West Seventh Street, which faces the museums, the architects faced a formidable challenge. The solution was based on the perspective from the Modern Art Museum’s lobby, which looks out across a reflecting pool to Camp Bowie Boulevard and beyond. A south-facing tilted curtain-wall facade was designed for 3131 West Seventh Street, a wedge-shaped building with three stories of office space over ground-level retail space. The curtain wall reflects the seasonal changes in the museum’s landscaping. The northern facade on Seventh Street makes a transition to a brick facade, tying it to the common materials of the buildings along this street.

The tallest building at eight stories, One Museum Place, located on the eastern edge, fronts the Seventh Street commercial corridor and anchors the Six Points intersection. Across from it to the east is a 6,000-square-foot (560 sq m) Museum Place post office, completed in 2009 and designed by Venturi Scott Brown & Associates. It serves as a gateway into Museum Place at the corner of Bailey Avenue and University Drive and is accessible from Sixth Street off Bailey.

| A south-facing tilted curtain-wall facade was designed for 3131 West Seventh Street. |

The street edge, particularly on Seventh Street through the project, is controlled to consistently enclose public space, interrupting the massing with receding and projecting facades and upper-level terraces to mitigate a fortresslike wall. Where building heights differ significantly, the taller buildings were stepped back from their neighbors over the course of several stories and include compatible banding or similar elements that align with a horizontal plane on the next block.

Design Flexibility for Building Use

At One Museum Place, a mixed-use building, the architects and structural engineers created an optimal depth for a condominium unit by setting one column each at the exterior and at the corridor. Cantilevered balconies on the facade project over the depth of the office floor plate below, a solution that permitted the design firm to pull the column back behind the glass on the retail level. It also gave the developer the flexibility to respond to market changes by switching uses in the upper seven floors until late in the construction-document phase and beyond. One Museum Place provides 23,000 square feet (2,100 sq m) of ground-level retail space, 100,000 square feet (9,300 sq m) of office space on the four lower floors, and 34 condominium units on the three upper floors. Office and residential uses have separate lobbies; a private bridge from the garage provides access to the residential floors.

Flexibility to deal with the weak economy is also built into the retail space. Should the space not lease as expected, its double-height spaces allow the addition of mezzanines to create live/work units, with ample light and air provided by tall windows. Or it could be configured to provide more office space to enlarge net rentable space, increase income, and reduce effective rent per square foot.

At the northwestern corner of the project, the developer built a new convenience store for the residents of the three-story townhouses to the north, the single-family homes beyond, and the one-story galleries and shops on Seventh Street to the west. The primary retail tenant is a new, more upscale 7-Eleven store with no gasoline pumps—a new concept the company is testing in Fort Worth. Five condominiums with tuck-under parking were placed over 4,500 square feet (418 sq m) of retail space.

The codevelopers of the Museum Place project, Fort Worth–based JaGee Holdings LLP and TLC Urban, completed construction of the $200 million project in January 2011.