The sight and sound of giant incinerators burning tons of trash in the heart of Nashville’s urban core have been replaced by musical performances and picnicking families, tourists snapping photos, and occupants of surrounding offices, apartments, and condominiums experiencing the city’s new Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Gold–certified riverside amphitheater and park.

“For 30 years, dump trucks backed up and dumped their trash at this spot. Now it’s the city’s new front porch,” says Kim Hawkins, founding principal of Hawkins Partners, a landscape architecture and planning firm based in downtown Nashville.

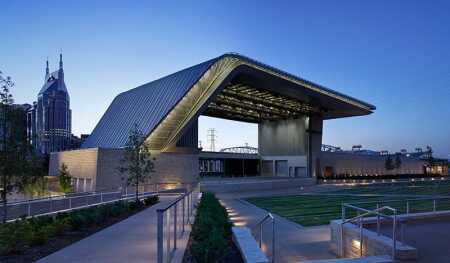

Hawkins Partners had a leading role in designing the new 6,800-seat Ascend Amphitheater and the 11-acre (4.4 ha) West Riverfront Park. Nashville-based Smith Gee Studio is the architect of record.

“This project has been completely transformative for that part of downtown,” says Hunter Gee, a principal at the firm.

During the early 1970s, Nashville became the first city in the world to burn solid waste as a source for heating and cooling nearby buildings. For three decades, the facility burned up to 1,000 tons (907 metric tons) of waste per day. Late at night, large dump trucks hauling away the residue rolled through downtown streets, sometimes spewing clouds of ash in their wake.

After reconsidering the costs and environmental consequences of operating the trash-to-energy plant on the south side of downtown, the city built a modern natural gas–fired facility and in 2004 tore down the old Thermal Transfer plant. That brownfield site sat idle for a decade, a period when Nashville’s civic leaders, business community, real estate investors, and citizens rediscovered the city’s downtown and the river that flows through it.

Over the years, the site was considered for mixed-use office development, a baseball stadium, and a music venue. Following the historic flood of 2010, a master development plan for downtown identified an urgent need for green space. It was determined that the highest and best use of the former Thermal site was as public open space. A team of designers including Hawkins Partners and Smith Gee Studio was selected to move the concept forward.

“There was a desperate need for open space along the Cumberland River. Nashville has created a world-class civic space in a site that had been sitting fallow,” Gee says.

Karl Dean, the city’s mayor from 2007 through September 2015, identified three goals for the amphitheater project. It had to be a “park first,” he says, with a design that optimized park space. It had to be a world-class venue befitting Nashville’s heritage as Music City. And finally, the design had to be iconic, symbolizing the city’s culture and celebrating its brand. His goal was to complete the project by July 2015.

Just a year and a half after Mayor Dean announced his goals, recording artist Eric Church performed Ascend Amphitheater’s opening concert, standing on a stage with a green roof and a louvered back wall that opens to frame the city’s skyline. The building’s design was inspired by the lines and textures of a 1962 Gretsch guitar amplifier, and the sinuous curves throughout the park reflect the morphology of the Cumberland River.

The stage provides a state-of-the-art electronic shell that enhances acoustic performances with small overhead microphones that create the same reflections a performer would hear in a concert hall. It is one of the just a handful of electronic shells in the world.

During Church’s performance, the audience sat on a grassy hill and in temporary chairs that in between shows are removed to make way for yoga sessions, picnics, and other pastimes.

To achieve Mayor Dean’s directive of “park first,” the architects designed each element of the park and amphitheater to yield to the other when needed. For example, the greenway through the park becomes the path for the concession area during performances. The greenway remains open but takes a slightly different route.

The amphitheater is built into a slope with a 35-foot (10.6 m) grade change that creates a natural bowl while providing unobstructed views of the surrounding city and the Cumberland River, a waterway where barges hauling coal, grain, and other commodities mix with growing numbers of pleasure boats. (Matthew Carbone)

“Nashvillians are discovering that the site is a park first,” says Gee. “When artists are not performing, the amphitheater becomes part of the park. You can ride your bike to the front of the stage. Ride your skateboard.”

Secondary buildings and sliding gates form a permeable street edge that invites visitors inside where they can discover a fitness circuit, a bike-repair station complete with hand tools, an outdoor classroom area, and porch swings. Visitors can play checkers or Ping-Pong or let their pets frolic in the fenced dog park. A half-acre (0.2 ha) botanical garden and an arboretum with 38 species of trees are curated in cooperation with Cheekwood, the city’s suburban botanical garden and museum, and the Nashville Tree Foundation.

The 267 trees in the arboretum are a precious addition. Just 4 percent of downtown Nashville has a tree canopy, says Hawkins.

“There are birds everywhere, bees, butterflies. We’re seeing the life return,” she says.

The amphitheater is built into a slope with a 35-foot (10.6 m) grade change that creates a natural bowl while providing unobstructed views of the surrounding city and the Cumberland River, a waterway where barges hauling coal, grain, and other commodities mix with growing numbers of pleasure boats.

“In a lot of ways, the river is the stage,” Hawkins says.

Many of the park’s key elements are out of sight. A 400,000-gallon (1.5 million liters) underground stormwater harvesting system captures water for irrigation and avoids burdening the city’s water supply. A well that is 1,100 feet (335 m) deep also provides water. Permeable pavers—9,000 square feet (836 sq m) of them—prevent rainwater runoff. Sustainable heating, cooling, and electrical power are provided by 62 geothermal wells and a collection of solar panels. The amphitheater’s green roof minimizes its energy footprint.

The $52 million project has already proven to be a good investment for the city, attracting hundreds of millions of dollars in private investment in new office and residential developments.

“It’s not a stretch to say there has been $1 billion in investment since the park was announced,” says Hawkins.

Terra House luxury apartments and the high-rise SoBro apartment building are planned nearby.

Directly across the street, Houston-based developer Hines is moving forward with a 25-story mixed-use structure with 350,000 square feet (32,500 sq m) of office space, more than 25,000 square feet (2,300 sq m) of retail and restaurant space, and a ten-level garage. The building will wrap around a three-story historic building, which will be preserved.

Vikram Mehra, a managing director with Hines, said having the amphitheater and park next door enhances the appeal of the 222 2nd mixed-use building.

“They created this as a park first, with nice amenities and connectivity. It creates the stretch value for the project. Locations like this only get better over time. My views and my environment are going to be protected over time,” says Mehra.

The park will attract people to the area in the evenings, he says. Bridgestone Arena, Schermerhorn Symphony Center, the Ryman Auditorium, and the city’s new 1.2 million-square-foot (111,500 sq m) convention center are nearby. So are downtown tourist destinations such as Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge and the Wildhorse Saloon. A pedestrian bridge over the Cumberland River connects Nashville’s National Football League stadium with the park.

“The amphitheater is another destination. Even better, it’s located with a park that people visit every day,” Mehra says.