A Seattle developer pioneers a flexible process to bring live/work/make/eat/shop uses to a superblock site on Portland’s inner urban fringe.

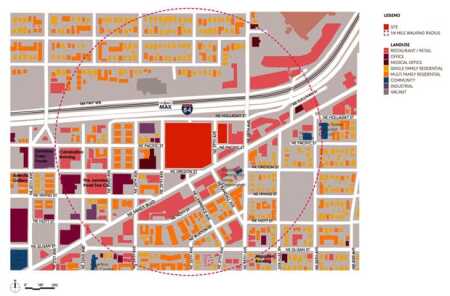

Finding four-and-a-half city blocks, including the land formerly occupied by internal streets, only 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from downtown Portland, Oregon, gave Seattle-based Security Properties the opportunity to develop the first project using the city’s new planned development review entitlement process established for large sites of over two acres (0.8 ha).

This process entitles a development’s capacity, heights, and overall configuration with some flexibility, recognizing that market forces and other factors may change over time. In January 2019, the city granted Security Properties—in return for providing publicly accessible open space, affordable housing, and energy-efficient buildings—the right to construct buildings up to 120 feet (37 m) tall and increase the floor/area ratio (FAR) from 3:1 to 5:1. Work has begun on the first phase with construction drawings; construction is scheduled to start in the third quarter of 2020 and be completed in 2023.

Mixed-Use Synergies

Security Properties expects the development, named Pepsi Blocks, to total about 1.2 million square feet (115,000 sq m) of space and include up to 1,130 residential units, 450,000 square feet (42,000 sq m) of offices, and 30,000 square feet (2,800 sq m) of retail shops. Housing predominates in this mix. “We are primarily housing developers with some experience in commercial and office, so we wanted to establish a new mixed-use neighborhood weighted to housing that dovetailed with our expertise that we could develop over an extended period of time,” says John Marasco, chief development officer of Security Properties.

The property is the former site of the Pepsi bottling plant, which has as its most prominent feature a 38-foot-tall (12 m) intersecting barrel-vaulted, glass-walled pavilion built in 1962. Its southeast corner touches Sandy Boulevard, a major urban commercial arterial road that runs five miles (8 km) diagonally through the east side of Portland and is in the early stages of transition to a more affordable urban mixed-use alternative to the Pearl District, the trendy former warehouse and railyard area just northwest of downtown Portland.

Culinary Destination

That immediate area bordering Sandy is turning into a foodie haven for Northeast Portland’s burgeoning creative class. The Pepsi Blocks are directly across NE 27th Avenue from the Zipper, an 8,000-square-foot (743 sq m) collection of bars and restaurants with indoor and outdoor patios. It is two blocks from a 7,600-square-foot (706 sq m) site called the Ocean, a collection of micro-restaurants, and the 10,000-square-foot (930 sq m) Providore Fine Foods, a multitenant group providing prepared foods and gourmet groceries. Providore’s anchor tenant is Pastaworks, a fresh sheet pasta maker, and its Mediterranean wood-fired rotisserie, Arrosto. Other tenants include a purveyor of grass-fed beef, a seller of sustainable fish, an oyster bar, a produce market, an organic baker, and a shop selling locally grown flowers.

The Pepsi Blocks pavilion could accommodate a large food hall or be divided for two to four tenants. “Although we would love to be the home for Portland’s first Eataly [a 35-location multifunctional marketplace dedicated to Italian cooking], we are taking a more realistic approach to its use,” Marasco says. “The space would be ideal for a specialty grocer with food service similar to Providore just west of us, but we recognize that the market may not support more specialty grocery.”

Shared Streets

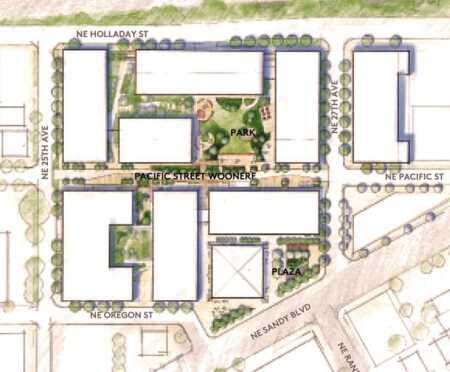

To knit the site together, Seattle-based architects Mithun will reinsert the original streets. But the east–west, 50-foot-wide (15 m) Pacific Street is reconceived as a woonerf (Dutch for living street), a landscaped, low-speed roadway without curbs or gutters, shared by pedestrians, bikes, and cars. The north–south NE 26th Street is designed as a public-access mews, solely for pedestrians, leading to a publicly accessible quarter-block internal park provided by the developer.

Mithun design partner Bert Gregory notes that reopening Pacific Street creates an unusual condition: the developer owns and can develop both sides of the street for more than two blocks in each direction. That gives Security Properties several functional benefits it can maximize, even though the city requires the developer to dedicate Pacific Street to the woonerf. The design and development team notes that one major benefit of controlling the woonerf frontage is that the team gains control of design at the street edge, which is critical to creating an interesting urban neighborhood. The reinserted woonerf street becomes a focal point for live/work/make/sell units that will line the new neighborhood connector. So far, rehabilitation on Sandy Boulevard has been sporadic, but the 4.5-block mixed-use project is positioned to become a vital urban node along it.

Another benefit is that the woonerf, the north–south through-block connections, and the park and plazas are considered areas common to all the lots in the planned development and count toward the city’s requirement that 15 percent of the project area be open space. A covenant with the city ensures that the ongoing preservation, maintenance, and operation of the publicly accessible open space and the energy efficiency features continue to be provided for at least 20 years after the certificate of occupancy is issued. The developers have created an association for maintenance of those elements through which subsequent property owners of each parcel will contribute according to an allocation based on their as-built development density.

Flexible Street-Level Uses

In the first phase, eight tall-ceiling live/work/make/sell spaces each include a shell and core commercial storefront of about 800 square feet (74 sq m) and a loft with living space above. These live/work spaces average a total of 1,867 square feet (173 sq m) and will rent for $3,500 to $4,500 per month. Other building end-cap spaces are flexible enough to accommodate restaurants, cafés, or other neighborhood services like a dry cleaning drop or fitness uses such as barre, spin, or Pilates classes.

At 1,072 square feet (100 sq m), the townhouses are smaller than the live/work units and rent for $2,500 to $3,500 per month. “We’ve done this particular townhome in the podium of many of our mixed-use developments with great success, especially in the Portland market,” Marasco notes. “We’ve found that residents tend to be slightly older couples who like direct access from the street with more of the feel of a home than an apartment.”

He continues: “I think the primary functional benefit of owning both sides of the streets is that we are able to be very flexible in the ultimate development of future parcels. For example, if we are able to secure a large single-tenant lease for an office use, but we need to change the building program by creating a larger floor plate to suit the tenants’ needs, we have the flexibility to do that and reconfigure the parcel lines and open spaces.”

A Developing Office Corridor

This location is not a traditional one for 300,000 to 450,000 square feet (28,000 to 42,000 sq m) of class A office space. However, over recent years a developing office corridor on the near east side of the Willamette River has attracted several tenants, primarily tech firms, which have relocated after outgrowing their spaces downtown and in the Pearl District. In addition, there has been consistent growth in health care stimulated by Providence health care facilities one mile (1.6 km) to the east. Marasco thinks this location can take advantage of the 120-foot (37 m) height limit under the planned development agreement. Two current parcels for potential office development would support buildings that are eight stories tall; each allows about 140,000 square feet (13,000 sq m) of office space.

While the project is planned to be transit friendly and easily accessible to east side neighborhoods—it has an 89 Walk Score, 87 Bike Score, and 59 Transit Score—Security Properties has planned office parking ratios higher than those downtown, with 1.5 spaces per 1,000 square feet (93 sq m) of office space and 0.7 spaces per unit for residential space, all located underground (235 spaces plus 240 bike stalls in phase one). The higher parking ratio is needed to help attract tenants to an urbanizing mixed-use neighborhood. A new streetcar line on NE Sandy Boulevard to the Hollywood District is being considered by the city, and the site design accommodates a potential stop.

Inclusionary Housing Solutions

The scale and variety of uses permitted in the multiblock project are also a key to its feasibility. Portland adopted an inclusionary housing (IH) requirement, effective February 2017, for buildings with 20 or more units outside the Central City Plan District, where Pepsi Blocks is located. It mandates that 15 percent of the project’s units be affordable to households earning 80 percent of the median family income (MFI), or that 8 percent of the units be affordable at 60 percent of MFI.

“We were able to purchase the property prior to rezoning and approval of the planned development at a land cost basis that was feasible given Portland’s new inclusionary zoning requirements,” Marasco says. “The major impact of the inclusionary housing policy is on land value,” because of its reduced capitalized income stream.

“Our strategy to minimize the economic impacts of inclusionary housing requirements stems from our long history of developing and owning affordable housing,” Marasco says. “We felt that if we could develop all of the affordable housing for the entire development in the first phase, we could not only set the tone and design for the project, but also maximize land value for future phases that would not be required to include affordable housing in their development.” He notes that his company would not have been able to build more market-rate housing units without inclusionary zoning because although inclusionary housing is required in this zone, it was the inclusionary housing required on large-site projects that qualified it for density and height bonuses.

A creative way that Security Properties was able to meet the inclusionary zoning requirements was to be among the first to exercise option five of the city’s IH requirements, which allows developers to build larger units with more bedrooms instead of a larger number of small units. Applicants for project approval may provide an alternative mix of affordable housing based on counting the total number of bedrooms, rather than units. Redistributing bedrooms into affordable units with two bedrooms or more results in a building with fewer affordable units, but units that are larger to accommodate families.

Most urban developers build limited numbers of three-bedroom units. By building 12 three-bedroom units among the first 218 units, which account for 12 percent of the 293 bedrooms in its unit mix, affordable at 60 percent of MFI, Security Properties could more than satisfy its 8 percent requirement while only accounting for 6 percent of the total number of units. These three-bedroom units average 1,316 square feet (122 sq m) and rent for $1,058 per month, under the rent limits published by the U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in 2019.

“There were several reasons for including three-bedroom units in our first phase of housing,” Marasco says. “Because we are not in the downtown core, we felt there would be more opportunity for more family-oriented units in this location that could take advantage of the large landscaped plaza and park spaces that have been included into the design. In our case, we felt it was most beneficial economically to meet the criteria for bedroom count, which also helped meet the city’s needs for more family units––a win/win for both parties.” The developer thinks the affordable family units will also mix well with renters attracted by the larger townhouses.

Security Properties is targeting the creative-class submarket for the largest portion of its market-rate units. “With tech as a significant employer in the Portland market, we believe our primary demographic will be in the 20-to-35 age range with household incomes of $60,000 to $150,000,” Marasco says.

Why might its market-rate housing be more competitive than existing or planned alternatives? “We believe the project’s open spaces and unique landscaped woonerf, with uses that are synergistic with housing, will set us apart from other infill development nearby,” Marasco says. “We may even pull from those looking at more urban choices downtown and in the Pearl; we certainly will be a more affordable option.”

Design Efficacy

The development plan design includes eight new buildings in the four blocks, ranging in height from 87 to 120 feet (27 to 37 m) and arranged around a quarter-block internal park, the new woonerf, and pedestrian streets that divide the blocks. It also highlights the intersecting barrel-vaulted pavilion and plaza in the southeast corner along Sandy Boulevard. Building scales are consistent with Portland’s historic small block pattern, with no portion of a building more than 200 feet (61 m) long. (See “Northwestern Small Blocks: The History and Rationale Behind an Urban Model,” Urban Land, November/December 2016.)

Typical building widths are 75 to 100 feet (23 to 30 m). The shortest buildings are located along NE 25th Avenue, which is occupied by smaller-scale residential and office buildings, while the tallest buildings are located along Interstate 84, which is depressed about 15 feet (5 m) below the project, so its impact on the site is minimized. The ground floors of these buildings have a mix of active uses to encourage a vibrant pedestrian environment. Retail space is oriented toward Sandy Boulevard for visibility and connection to the existing retail businesses, and live/work and active uses are located on the Pacific Street woonerf.

That design enables a variety of construction efficiencies. Most of the residential units can be located in five stories of more economical wood-framed construction above a concrete podium. Those economies permit more affordable and competitive rents. Open pedestrian bridges connect residential floors in many buildings, reducing the need for elevators. In addition, by being built above pedestrian streets, the bridges can activate upper levels as well as the streets they overlook. This design also eliminates the design inefficiencies of inside corners of L-shaped alternatives while creating brighter and more desirable corner units.

As part of its development agreement with the city, the developer will reduce building energy use intensity (EUI, the energy use per square foot of space) to levels that are 50 to 70 percent below baseline EUI standards for each use in the project. For example, office space will use no more than 23,800 British thermal units (23.8 kBtu) of energy per square foot rather than a 79.3 kBtu EUI standard baseline, and under the agreement, the developer will certify those use levels annually for 20 years through the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Energy Star Portfolio Manager or other approved sustainability certification program.

Progressive Phasing

A project of this scale requires phasing, and this one will proceed in five phases starting with the pavilion and its pedestrian plaza on Sandy Boulevard in the southeast corner, flanked by two six-story residential buildings with a total of 218 units. Development will proceed clockwise, moving west to NE 25th Street and then to the northern parcels along I-84. The north and east parcels, which have been allocated the highest FAR, can be built up to 120 feet (37 m) high, which works well for offices in a new location. Phasing produces economies for the project management team and construction partners, allowing them to plan efficient teams for construction over an extended period of time, while the flexibility of the planned development agreement permits the developer to fine-tune its program as it builds.

In cities like Portland where developers have been constrained by new inclusionary housing requirements, statewide rent control, and high systems development charges, the Pepsi Blocks project suggests that a flexible development process awarding adequate density bonuses can bring live/work/make/eat/shop uses to a 4.5-block former industrial site on Portland’s inner urban fringe and create a mixed-use node on an urban artery.

WILLIAM P. MACHT is a professor of urban planning and development at the Center for Real Estate at Portland State University in Oregon and a development consultant.